Debunking the myths – Justine Clark’s presentation to Making, the Australian Institute of Architects National Conference.

Cliches abound about women in architecture – many of which are destructive and detrimental. This piece responds to six common myths about women and architecture through both statistics and anecdotal evidence drawn from the two Parlour surveys. Quotations from the surveys are colour coded – white for women, blue for men.

All the myths I discuss are complicated, big and fairly firmly entrenched. I don’t have the space to unpack them in any detail, nonetheless it is important to challenge them if we are going to develop alternative stories and strategies. I have spent a great deal of time recently working on the Parlour Guides to Equitable Practice, which present a very positive approach to the opportunities, so I am conscious that the process of dismantling myths may sound overly negative, but please bear with me. We will get to the good part soon.

But before I start there are two even bigger myths that frame all of this – one about architecture, and one about gender.1

Architecture is a meritocracy

That is, if you’re a really good designer you’ll succeed and be recognised and become famous and be showered with architectural commissions. The problems with this myth are twofold. Firstly, it doesn’t prepare architects with the political and social skills they need. Secondly, it hides the structural issues that impact on almost everyone’s careers, for good or bad.

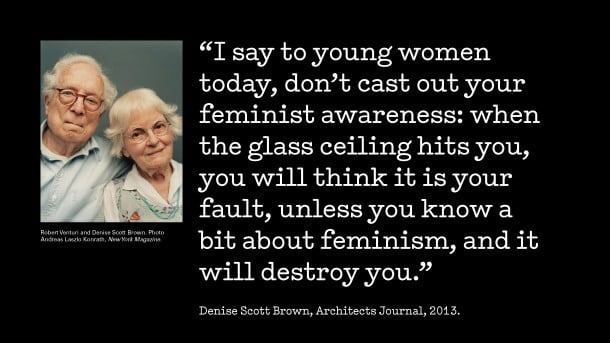

Both advantage and disadvantage are cumulative, they build up over time via many small things. This is important because inequity is experienced differently at different career moments. Indeed, many women in architecture do not experience any difficulties until they are in their thirties. They often don’t notice what is happening for quite some time and, as Denise Scott Brown points out, this can be a terrible shock:

When advantage accumulates we may to not recognise the structural circumstances – we are proud to be doing well, and assume it is simply because we are talented, committed and hard working. In contrast, when things don’t go quite as we expect, many women (and some men) tend to blame themselves, rather than thinking about how to navigate the wider structural situation.

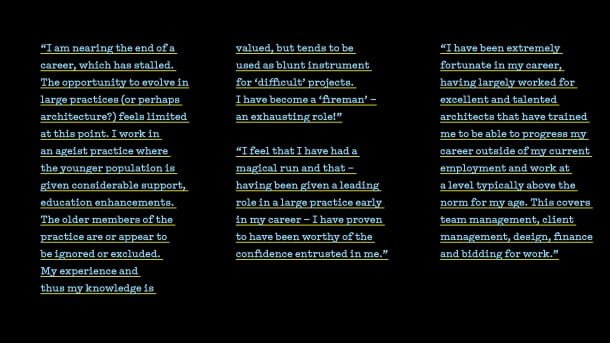

Talent, commitment and hard work do matter, but structural, social and cultural factors, behaviour and expectations can promote and support some people’s talent and hard work, and can undermine and compromise others. One of the things I like a lot about the following quotes is that they recognise these factors.

Succeeding as an architect requires the right alignment of social, cultural and political factors as well as talent and commitment – and the better we understand this, the more strategic we can be. It also requires support and trust from those who can help make opportunity.

Gender is a women’s issue

Although our research explicitly addresses women in architecture it is important to remember that gender is not a synonym for women. Gender-based stereotypes are also constraining for men and gender inequity is a societal problem that needs to be addressed by us all.

This quote from Architel is worrying. It suggests that while many women are delighted the topic is being broached, a sizeable proportion of men switch off.

Last week’s newsletter, announcing our new Women In Architecture series, was our most shared newsletter so far – nearly viral.Also, ironically, the newsletter has received the most ‘unsubcribes’ to date – all from male readers!” — Architel, March 24

We should also note that we are talking about women and men as groups. This can lead to generalisations that might not chime with our own particular experiences. But it is by looking at the experiences of groups that we can identify structural factors. It is also important to have empathy and acknowledge a diversity of experiences.

None of this should set up an opposition between men and women. Making things better for women, will not make it worse for men. Indeed, many of the things that work against women in architecture also work against many men. But they tend to impact on women in exaggerated ways. And if things are to change with any speed, men need to be actively involved as well as women.

So, on to my myths about architecture.

Myth 1 – There is no issue for women in architecture.

In my experience, this tends to come from two groups: older men – many of whom are very supportive of individual women – and young women who have not themselves experienced any issues – yet!

One survey respondent sums up the argument:

“I find it intriguing that you want to survey men and women architects separately. I have worked with or known many capable and recognised professional women (and non-professionals but highly competent). I don’t think they ever saw themselves as held back by a ‘glass ceiling’. They just made sure they did a damn good job with professional and competent commitment to their work, and the results and promotion in their careers came along … just like it does for men with the same expertise and commitment. And one must recognise the fact of life, that not everyone has the same abilities or commitment to their profession, probably for good reasons such as family, other interests, personal issues and maybe not being in the right place at the right time.”

Of course, some do recognise that women have different careers to men, but see this only in terms of broader societal structures, and don’t think that architectural culture or workplaces have any impact.

Many younger women see it all as a thing of the past – they have done well so far and see no reason why that won’t continue. The battles have already been fought, and they will reap the rewards. (I thought the same thing 25 years ago.)

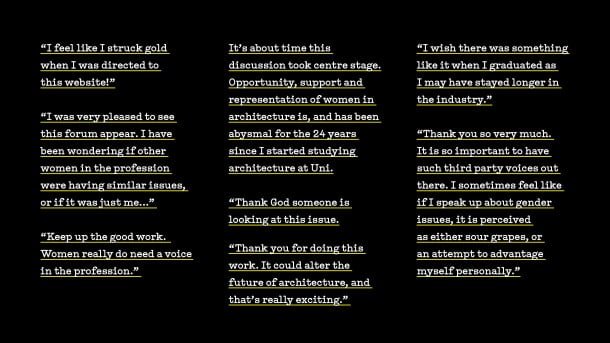

The blunt answer to all of this is that if a large number of women feel there is a problem then there is one – below is just a tiny sample of relieved responses to Parlour.

Both statistics and anecdote suggests that many women have unequal opportunity in the profession. Of course, this does relate to broader societal inequity, but there are specific factors in architecture that impact much more negatively on women than on men.

It surprises me that we still need to demonstrate that there is a problem, but here is a quick overview of the statistics. This beautiful graphic was compiled by Gill Matthewson with Georgina Russell and Kirsty Volz. It shows the percentage of women in the profession via a number of measures. (The proportion of women are shown as the solid colour dot, with the outline showing the proportion of men.) It succinctly demonstrates that in all areas, women are disappear as seniority increases.

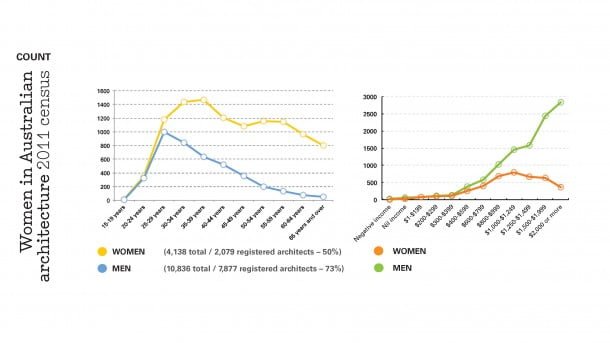

Data from the census makes a similar point even more bluntly. The graph on the left shows proportions of men and women according to age – note the major drop-off after thirty. When we remember that women have been around 40% of all architectural graduates for almost the last 30 years, we can see that it is not a ‘pipeline issue’ – or at least that the pipeline tends to leak women.

The chart on the rights show income. Of course the difference at the higher end can partly be explained by the fact that the are many fewer older women. Nonetheless, it points to a significant power imbalance in the profession.

Lastly some charts from our own surveys. At a glance we can see that a high proportion of women are employees, that only half the respondents are registered, that women cluster in the lower salary range, and that many women and men work rather more hours than they are paid for.

We need to dispel this myth, and acknowledge that many women do experience unequal opportunity so that we get on with changing things for the better.

Myth 2 – It is because of the macho culture of the building site.

Otherwise known as the “it’s-not out fault” response. Now, some women may experience discrimination on the building site, but many who do find it much easier to develop strategies to manage or neutralise this, than they do to counter much more subtle but pervasive disadvantage and inequity in the office. We don’t have any statistics on this, but many of the people who responded to the survey – women and men – point to the uneven opportunities within architectural practices.

It is important to note that not all practice are like this. Nonetheless, architecture needs to look to its own workplaces – to seriously consider what sort of behaviour is rewarded, how are people promoted, and who gets the opportunities.

We aim to help with positive and productive strategies for workplace change in the Parlour Guides to Equitable Practice.

Myth 3 – Women don’t want the big jobs. / Women aren’t ambitious.

I find this one particularly insulting. Overwhelmingly, our survey responses express a desire to be highly active in the profession and to do good work. But this is in tension with the many other responsibilities that women carry, especially as they get older. A reasonable number of men also feel this.

We could argue that many women are very ambitious – they are ambitious for the quality of the work, and for combining this with having a life. Simply managing this means that there may be little time / energy left for climbing the traditional ladder. This leaves some disappointed and disillusioned but it doesn’t indicate a lack of ambition.

We only need to look at how very well women do in architecture school, and in the early years in practice to dismiss the idea of a lack of ambition. We need to turn instead to structural issues.

- Research in other fields suggest that women are less likely to be given the “hot” jobs that help advance a career – comment in our survey suggests that this is the case in architecture too.

- Many women comment that they end up organising things and managing situations, rather than in the more glamorous roles. Some men also observe this. This also raises the question of what roles we value and valorise as a profession.

- Many women end up in small practice, not because they actively choose not to work on big projects, but because they find themselves with few other options. Others leave for more fulfilling and manageable careers elsewhere. This means that the profession is missing out on an enormous amount of skill, talent and knowledge.

This is a really dangerous myth. We need to reframe it as “women find it more difficult to access the big jobs” and explore what we can do about it.

Myth 4 – It is because women have children.

So, it turns out that this is true. Kind of. This has been the biggest surprise for me from the research. Initially I thought this was a red herring that masked other significant issues. Of course many women have children, but – surprise, surprise – so do many men. And substantial research in other fields shows that women without children also experience delayed careers progression, lower salaries and the rest.

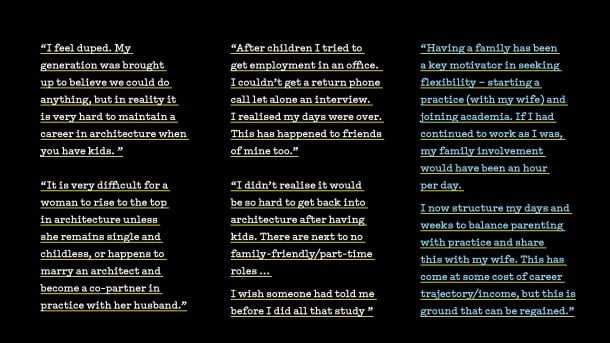

Our research made me realise just what a big issue this is in architecture – but it is really important to remember that is is not the only issue, inequity is the cumulative layering of many factors. Nonetheless, an overwhelming number of women point to enormous difficulties within the architectural workplace once they had children. And when asked at the end of the survey if there was anything else to say, a very high number of women wrote again of the difficulties of balancing work and family, and the negative impact that having children has had on their careers. Only four men (out of 914) made similar comments.

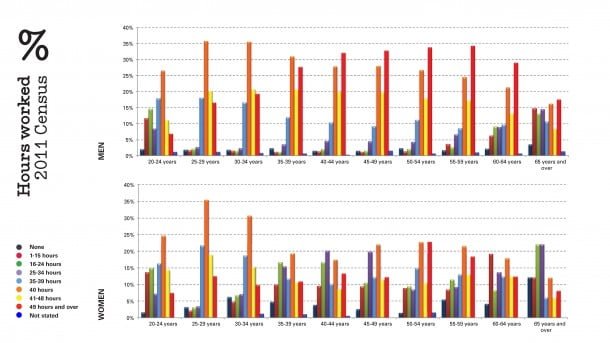

There are two main issues. Firstly, the impossibility of working long hours when you are also the primary carer of children (or an elderly parent, for example). This chart from the census shows just how widespread long hours are in architecture. The red bars show how many regularly work more than 50 hours per week – an average of 30% of men over 35 do this.

If we look at the same data by numbers (not %) we see that this is a particular problem for men – or perhaps is is rather that men are able to work these kinds of hours because someone else is managing any caring responsibilities their family may have.

The second issue many women face is substantial changes in the way their employers perceived them – as no longer being serious enough or committed enough. Many found this particularly upsetting. And, as one respondent points out, this is not just about those with children – it impacts on anyone with caring responsibilities.

The problem is not that women have children, but about expectations of what it is to be an architect – and perceptions that this can’t be done while also caring for others. These need to change.

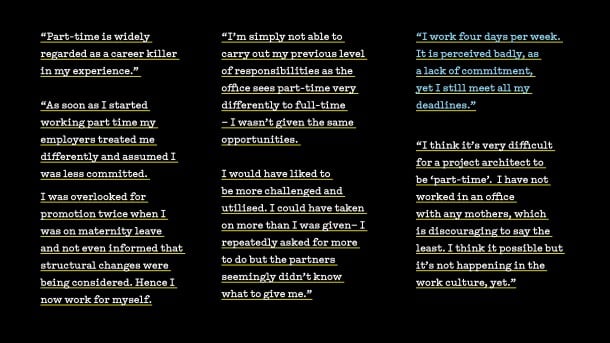

Myth 5 – You can’t be a part-time architect.

This is a very widespread myth and relates to the above. There is a big difference in opinion between those who want to work part-time, and consider themselves efficient and capable with significant expertise, and many – but not certainly not all – employers (who themselves certainly wouldn’t be working full time on any one project).

These two attitudes are succinctly expressed in the slide below, which shows two quite different survey responses.

The 2011 census data also suggest that architecture is less supportive of part-time work than other professions, and that this is particularly a problem for women.

Indeed, men and women seem to experience the impact of part-time work differently. Of our survey respondents, 60% of men who had worked part-time said it had had a positive impact on their career. Whereas only 26% of women said the same. This also seems to be largely about perception.

Working part-time because you are caring for children is widely seen as a career killer. However, working part-time due to study, or other professional commitments is looked on much more favourably. This perception needs to change. Of course, it may be very difficult to work part-time as a project architect on certain types of large projects. But this is not the only kind of meaningful work that architects do.

There are clear business advantages for those practices that do accommodate part-time work, and some practices have shown that it is perfectly possible for architects to work part-time, make a serious contribution and have a fulfilling career.

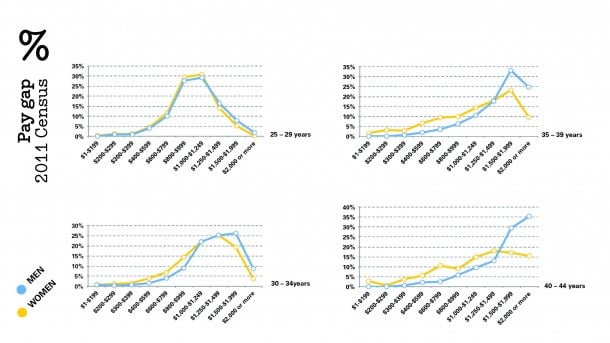

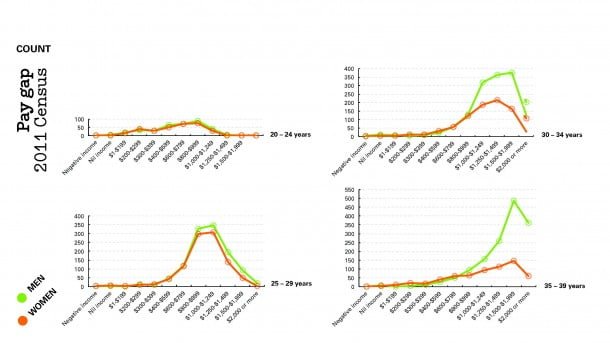

Myth 6 – There’s no pay gap in architecture. / If women are paid less it’s because they ask for less.

There are multiple indictors of pay gaps in architecture, and the reasons are complex. Gender pay gaps build up over time, and may be the outcome of an accumulation of small things, which are often invisible and accidental. They also relates strongly to opportunity – and many of the previous slides suggest that many women find less opportunity.

This data from the 2011 census shows that women are consistently over represented on the lower salary brackets and under represented in the upper salary levels.

If we look at numbers (rather than percentages) the differences are even more stark – numbers rather than percentages doesn’t directly indicate a pay gap, but they so point to a significant power imbalance.

There are many reasons for pay gaps, but one that is frequently cited is differing negotiation techniques. Research in other fields suggests that women (as a group) don’t negotiate as often as men or ask for a much. However, there is other research that suggests that when women do they are seen as pushy – damned if you do and damned if you don’t!

But other research shows that it is not difficult to establish circumstances in which women negotiate more effectively – for example, when the grounds and parameters for negotiation are clearly identified women can in fact turn out to be better negotiators.

In conclusion

There are many factors that build one on top of each other to make things very difficult for many women in architecture. These include:

- Long hours

- Poor workplace cultures

- Poor part-time and flexible work options.

- Incorrect and sexist perceptions about women in the profession.

- Very narrow views of what an architect is and does.

But I want to end on a more hopeful note, with a comment from one of the male respondents to the survey that makes my heart lift. Because of course this project is about more than debunking myths. It is also about having an positive and productive impact – and to this end I would encourage everyone to read the Parlour Guides to Equitable Practice and to put them to good use!

- My comrade, colleague and friend Karen Burns pointed this out when I first started looking at these myths.[↩]

2 comments

n k says:

Oct 2, 2015

This well researched article has brought tears to my eyes. I live in Europe – far away from you guys and am experiencing just that: I had a great career, worked in top practices, was always committed and worked long hours.

Now, that I have two children I have had difficulties finding part-time work (to put it mildly). It feels like I am running against a brick wall! No response to my applications. However, as soon as I don’t state that I’d like to work part-time in my covering letter, I immediately get invited to job interviews…!

I always get asked personal questions: how old are the kids, how good is and what are the opening hours of child-care. I would be very surprised if any man gets these kind of questions. One of the architects even got mad at me for stating, that I would like some flexibility in working hours. I got a full lecture on the economy of part-time employees.

I am one step away from leaving this wonderful profession.

Justine Clark says:

Oct 5, 2015

Hi NK,

I am very sorry to hear your story, which sadly is all to familiar. I do hope you find a way to stay in the profession. Are you familiar with the Guides to Equitable Practice? They might help you with some arguments back the next time an idiot gets mad at you.

Justine