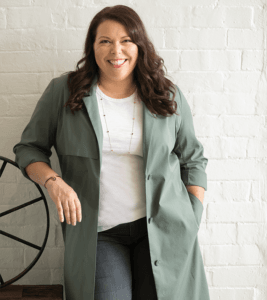

The 2018 winner of the Paula Whitman Prize for Leadership in Gender Equity Melonie Bayl-Smith has a lot on her plate – founder and director of Bijl Architecture, elected member of the NSW Architects Registration Board, adjunct professor at UTS, professional mentor, mother of two. Susie Ashworth recently met Melonie for a wide-ranging discussion about transferable skills, what tough times can teach us, and the power of saying no.

Photo above & thumbnail: Kirsten Delaney

On early influences

I had one uncle who was an architect and another who was a painter. He was a tradesman painter but in his spare time he was an oils painter, he did landscapes, and he did very fine drawings as well. We lived near him, so I used to see him a lot. Between those two uncles, I had a lot of encouragement about drawing and studying architecture and being interested in what was around me. On car trips I was always fascinated by buildings. I had a lot of early influence from my parents, who built a Pettit and Sevitt house in Singleton Heights when I was three. I can still draw the floor plan from memory! Then, when we moved, we bought a Sydney School type house designed by an architect, with glulam beams and clinker bricks on the inside and the outside, western red cedar lined raking ceilings and all that kind of stuff. It was split level. It ticked all the boxes. It was the long lost child of Ken Woolley.

My aunt also lived nearby in a very interesting, timber-oriented split-level house. I was fascinated by how things looked and how they were designed. So, I was always a bit torn. Though for a long time I considered studying medicine, all my friends who have known me since earliest primary school say they always knew I was going to be an architect. I was always designing cubby houses and buildings in the playground.

Eight years old and gazing at the architecture at the High Court of Australia. Photo: Paul Bayl (Dad)

On a rough start in architecture

When I was a student in the early 1990s, we were experiencing the ‘recession we had to have’ and there were no jobs. The industry was a nightmare at that time. I lived and studied in Newcastle, which made it even more challenging. Even getting unpaid work experience was difficult – and, of course, now completely illegal.

My first graduate experience was appalling. I had heard negative things about this particular architect, but I got the job, and I thought “Oh well, it’s better than having no job”. But he was a very cut-throat employer and I learned a lot about office politics there. People in his office didn’t like questions. They just wanted people to sit down, shut up and do mark-ups – whereas my philosophy is “There’s no such thing as a dumb question, but there is such a thing as a dumb mistake.” I say it to the builders, and I say it to my staff. It’s important to just ask the question, even if you think it may have been asked five times already. Ask it. It’s better to understand and have that learning opportunity.

But in the first job I had, they didn’t like questions. If you asked a question, you were considered stupid. It was short-term thinking. Also, this employer was very much an opportunist in the negative sense of the word. Someone a couple of years ahead of me at uni had left working for another practice. She had cold-called my employer looking for work. He saw that she had good project experience, that she could probably do X, Y and Z, and he probably didn’t need to pay her much more than me – so he hired her and very unceremoniously tried to fire me under the guise of the probationary period provisions. I took great umbrage to the way the whole event played out and applied for a hearing at the Industrial Relations Commission – and won… He didn’t follow any of the proper steps – even 20 years ago there was still a framework, and he didn’t follow any of it.

The outcome was that he had to pay me a few weeks extra pay and my legal costs. But of course, I was shattered. My confidence was shattered. And at the time in Newcastle there were very few architecture jobs in the city anyway, so finding a job past the start of the year was often incredibly difficult. I managed to find a contract position with a very nice couple of older gentlemen working on the Central Coast in Gosford. So, for six or seven months I commuted to the Central Coast and worked on the Gosford Art Gallery, documenting that project by hand. I learned an enormous amount about construction while I was there, and you couldn’t find nicer people to work with. They loved teaching me things. They were very grandfatherly in that respect. It was great to have those six months to feel like I could be myself and learn in a small office.

When the contract finished, I had to find another job, and that one was part-time. This employer was enthusiastic, loved to teach me things, and let me take responsibility when I wanted it. He was teaching at university, so I was often in the office on my own running projects. But the problem was that he was so absent that the workflow, and subsequently the cash flow, dried up and as a result he wasn’t able to pay me for a number of weeks. It was never his intention for me to be unpaid, but it just happened that way. I left working for him after 20 months, not just because of the pay issue, but also I could see that I wasn’t receiving enough guidance. It’s the problem of being a competent, energetic but inexperienced graduate. People start expecting that you can do more than you actually can. It’s something I have to be careful of with my own staff. They still need enough guidance, even if they’re really good at what they do.

So, then I went and worked for a small commercial practice of about 10 people. The director was giving me good design work on multi-res. He gave me very positive feedback about my performance. I was feeling really positive. I was thinking of completing my logbook. I’d been working in architecture for two and a half years, but my logbook was looking patchy in places. Then, six weeks after I started with the practice, it was announced that the other director was splitting away from the practice. There was all this stuff that was going on when they employed me, but they didn’t give me an inkling about it. I don’t know whether they considered me a gap filler who was going to be shown the door soon. Who knows what happened? Now, there was a division of projects and sure enough – last in, first out the door. So, one of the jobs I had been specifically hired for (multi-res development) was put on hold because the client said to postpone until the directors had “sorted their shit out”. And because this job was bankrolling the practice to some extent, they had to look for an opportunity to cut staff. But I had no idea. I was there around ten weeks – two weeks off fulfilling my probationary period – and again (like the first job) I was let go. I was very naive about it. I didn’t see the signs.

For years later, I saw one of the directors around at various talks and events, and he would often apologise to me. I told him on more than one occasion, “You did what you had to do. I understand that now.”

So, I had a rough start in architecture. But it also taught me important and quite different lessons (from different people) about how not to run a practice and how not to treat others.

Twelve-year-old Melonie “working” in her architect uncle’s office. Photo: Louis Bayl (said uncle)

On music and transferable skills

For a while in high school, I harboured an interest in doing music professionally – as a career. I did end up working as a pianist and accompanist professionally for a long time, and I do think that if ever I were to throw in architecture I could always go back and be a professional muso if I wanted. I taught piano for 10 years, which got me through uni. It also gave me all sorts of opportunities for earning money when I couldn’t earn money as an architect (sad but true).

In between my architectural degrees, I took a year off to continue my music studies. I remember some of my friends and colleagues saying things like, “This is so frivolous. Why are you not going out trying to get architecture work? Why don’t you move to Sydney?” But so much of what I learned playing music, I’m able to apply in the way I think about design, the way I think about practice, the way I think about presentation, how you interpret things, how you take on board working with different people. When I was working as an accompanist, I’d have a day when one moment I was working with a seven-year-old trying to get a decent sound out of a trumpet and then an hour later I’d be working with a professional opera singer. On those days I’d have to be so nimble and I had to show an enormous amount of empathy working with all these different people with all these various levels of experience and capability. With teaching piano, I also had to get into the students’ heads (kids and adults) to communicate ideas of how to bring the artistry together with the technical means.

People talk about architecture and music being similar to each other, but it’s a pretty shallow comparison – “architecture is frozen music”. The parallels are much more about the practice of being a musician and the practice of being an architect. I tell my Professional Practice classes at UTS that you need to be able to talk to, say, six different people about the same project. You need to be able to talk to the client and the council planner and the builder and the consultant and the funding agency and the media at the end. How do you take this one project and make it relevant to all those different people? It’s about empathy, about understanding how to communicate what’s important to them. The same applies in music.

I have continued to do music and architecture over the years, with one taking over more than the other at different times. I don’t see them as silos. Even now, I’ve just started learning drums. It’s new. It’s amazing. Pianists are pretty good with their independence with their hands and pedalling feet, but drums is a whole new level. It activates the brain in a different way.

I talk with friends about music and architecture. I have a conductor friend who says “Music has immediacy, but at the end of an opera they’ll clear all the set away and it’s like it never happened. At least your buildings don’t do that.” I say, “I hope not”. There’s the permanency and impermanency of art. By working in architecture and in music, I have the best of both worlds.

My piano teacher was very wise when she told me that I could always do piano, but I won’t always be able to do architecture. It’s true. Music will always be there.

Our practice has been a corporate sponsor of Sydney Youth Orchestras for five years, because education is a big part of our practice ethos. We’ve very supportive of what education can bring to individuals and to communities. I teach at Uni. We’re doing education projects in our practice. But we also support the SYO because that collaborative community activity of playing in a symphony orchestra is such a valuable experience. It teaches so many skills – thinking and listening to what other people are doing, working together, teamwork. Even on that very basic level, group music is amazing for that kind of skill level. I like to think we’re building ‘cultural infrastructure’ in our city.

On learning about professional practice

Where I teach at UTS, professional practice is taught in a way where we are very interested in what students learn about practice as well as the profession. How is the profession structured? Who dictates what the profession does? What’s registration? What are the competency standards? How do the professional bodies work? How do we relate to our allied professions? Understanding all those structures is helpful for students and graduates when they need to get out there and navigate. It’s an important part of what we do at UTS. I’m an examiner and a state convenor for registration. I’m very interested in these things. I have an awareness of what’s going on in the universities. Not every university teaches it that way. But I do believe that giving the students a sense of the structures and frameworks they will enter into when they leave is really helpful.

A comment I make to students is that we spend a lot of time teaching about design and strategy and looking for problems that need to be addressed, identifying a challenge, all of these kinds of ways of thinking and reflecting on the design process. Yet we don’t talk about it with students in terms of how they think about their career.

On biting the bullet and walking away

A lot of people say: “I’m just not getting the contract admin experience” or “They don’t let me do any design work” or “They just want me documenting”. More than a few times I’ve had to say to people, “You might have to leave that job. Don’t expect that anyone is thinking about the future of your career.” And they all go, “Woah”. But it’s the truth.

Yes, a good employer will mentor and think about the future of their junior staff, because ultimately they want to keep those staff for as long as possible. They might end up being future leaders in your practice, in the profession. They’re not just cheap labour hanging around down the bottom of the food chain. But I’ve had to say to many students and graduates, “You can’t expect that other people are looking out for your career path”. Even for an employer like myself, who tries to be in touch with what their staff want and what their goals are, and will sit down and have chats about these things a few times a year, it’s important to remember that things change for people. They get married and their partner wants to move to another city. Well, I’d rather put a staff member in a good enough position to give another job their best shot. It’s like paying it forward. It’s doing something for those individuals, but it’s also doing something for the profession. We want our profession to be as strong as possible.

But of course, not every employer thinks like that. Not every employer thinks of their staff as having a career trajectory. It’s very sad when I hear graduates saying “I don’t know how I’m going to study for registration because the practice where I work expects me to be in the office until 9pm every night.” And I say, “I’m very sorry that’s the situation you’re in. But if you think it’s not going to change, then you should really go somewhere else.”

And I’ve had quite a few graduates who have come up to me later and said, “I took your advice and it was the best thing I ever did.”

I look back now and wonder whether I could have changed things with some of my early jobs. I think an enquiring mind is better than a mind that just accepts everything.

On unconscious bias

It hasn’t personally happened to me, but I have so many friends who have been affected by it. The golden-haired boy comes in and is often no better than anyone else, but there is that identification problem. I can think of at least five women I know who ended up leaving because they were overlooked, because of actively not being promoted, coming back from maternity leave and finding out that some new young “jock” has turned up and taken their place. It’s awful to talk in that way with that language, but it’s true. The sorts of personalities who have gotten ahead, instead of some very fine female architects that I know, it’s hard to believe it still goes on. One of them left the profession completely. She was so disillusioned after working for a particularly male-dominated practice. She was always cleaning up people’s messes. I kept saying to her, “Don’t do it. Don’t clean up the messes. Take it to the Director.” But she just wouldn’t do it. And that comes back to confidence. It’s not just graduates who suffer from confidence challenges. And I’m sure there are men out there who have confidence issues as well, but they express them in different ways.

On presenteeism and long hours

There are still some large practices with a reputation for the long-hours culture. And it’s not just female graduates who are affected by this – it’s male graduates too. Staying back late at the office is often for appearances. My husband’s an organisational psychology researcher, and he talks about presenteeism. We’ve talked about how people get into a culture of thinking … because I’m going to be here so long, I’m just going to do things as I please. They’ll go on Facebook. They’ll be slow doing something. It starts to affect the way they present work to others. It starts to affect their overall work ethic and all sorts of other things.

Every profession is different of course. In architecture, the problem starts at university with the inevitable all-nighters. I don’t think they’re necessary. I think it’s just poor time management. When I was younger, I did lots of late nights, but I’m also a night owl. It suits me. Some of my staff say, “What are you doing sending emails to us at 1.30am in the morning”. But it’s because I go home at 5.30pm and I’ve got kidarama until 9/9.30pm and laundry and everything. A lot of other Directors I know work until 7pm and then they go home and don’t think about work. I’ve never been like that. I’ve always studied late, worked late. It’s just me.

Bijl Architecture’s Step Down House. Photo: Peter Bennetts

On time management, prioritisation and building layers of experience

Time management and prioritisation are key skills in practice – graduates do have to learn within the work context that you need to manage your time well and learn how to prioritise. It’s not about doing something quickly, which has its own issues. It’s about prioritisation, which is more complex than time management, because it’s about empathising and listening and thinking through what is going to communicate this piece of work, the design, whatever the client needs to know – or the council, or the consultant. Whoever it is. What is it that they need to know and how am I going to prioritise bringing that information and those decisions together?

People can get through an entire architecture degree and never actually really think about how they’re making design decisions. That’s a challenge that people in practice find is too time-consuming to solve. That’s why a lot of graduates get shoved into documentation where their decision-making agency is minimised. Many practices seem to start with documentation and over time you experience works outwards. You might get to go on site, you might get to sit in a meeting with clients and do design work. I don’t want people to be in a box. In my practice, from the beginning people can start to sit across all the different activities of the practice where they have the opportunity. You’re building experience like a layer cake.

I’ve had friends who had been working for 10 years before they realised, ‘Oh, I’ve actually never been to the client meeting. I’ve never been the one making the design decisions. I haven’t had a chance to go on site very much.’ If you don’t build the layers of experience for people, it becomes a real problem for long-term career progression.

On bad behaviour

Students can get so sucked in by the outward appearance of a practice. I’ve heard tales of very abusive, hyper-critical Directors. When you’re young and inexperienced, you might think, “Oh, well, this is what it takes to do amazing work. You have to put up with the abuse and the temper tantrums.”

But the idea of the ‘temperamental creative genius’ is a myth. I simply call it bad behaviour. There’s lots of bad behaviour in architecture that is perpetuated. Again, graduates with a sheer lack of experience or confidence start to accept things as normal, which really shouldn’t be accepted. This is where I try to help students to think about and critique where they want to work and why they want to work there. To be honest, we’ve had an economy that’s allowed that ability to pick and choose. That may change. That’s where I came from too. I was in Newcastle. There was a scarcity issue. I just took whatever jobs came along in a way. One thing I did do purposefully, though, was to avoid working in large practice, because I thought I might get stuck in a little pigeonhole. I know now that this is not necessarily the case at all, but my naivety guided my path at the time.

On the value of transparency

In situations where practices are not being run effectively, those who suffer are usually the junior staff, because they generally don’t often have the experience or awareness of all the other things that are required to run a practice. They don’t see the signs of something going wrong.

I learned from the former employer who kept me in the dark about the situation in the practice. I make sure I give my staff a lot of upfront information about what’s going on in the practice – not in a way that will have them worrying about cashflow and projects they’re not working on (I want them focused on their work). But I do want them to have an understanding of the general health of the practice. My early experiences were completely different to that.

Even a modicum of financial information about a practice’s performance once a quarter may be enough to empower people and put them at ease. It all comes down to communication and what you communicate. I think some Directors feel that they can control staff by not telling them anything, but I have learned over time that sharing the right pieces of information and being upfront about challenges in the practice has ended up engendering respect and empathy and positive suggestions from staff.

Being open and honest is not about being weak either. Showing vulnerability as a leader is important, because it shows that not everything’s perfect, not everything’s under control all the time. Showing vulnerability demonstrates that you are exercising a self-awareness. I think some of the people I worked for, even the really lovely people I worked for, had very little self-awareness. And I’m certainly not claiming that I have this down pat. I still struggle with some of those things.

The Bijl team from left to right: Andrew Lee, Natasha Grice and Giles Gibbins (standing) and Rachael O’Toole and Chelsea Dawson (seated). Photo: Kirsten Delaney

On the importance of the expanded field

I’m very supportive of the expanded field. The more places we see with employees who are architecturally trained the better, because we’re then building a bigger profession and a bigger built environment realm, where architects are not just sitting in one spot but in all sorts of key areas.

At the end of the day, we’ve got to fight this stupid lie that we keep telling students that everyone’s going to be a star designer. No, we’re not teaching design because everyone’s going to be Zaha or Bjarke. We’re teaching design so that even if you are the person who’s amazing at specification writing you understand the purpose of the design and what the architect is trying to achieve, and understand what design can do. It’s important, even if you are sitting in your speciality and you never pick up a pencil or a mouse to design anything. We have to set the expectations better with students about the many places they can go within the profession and outside the profession – and making sure all of these roles are discussed equitably. If we keep lionising the “top-of-the-tree” starchitects, of course we’re going to continue to have students who get five years into their career and wonder “What did I do that for?” I don’t mean that we should push everyone into specialisations. It’s just making people aware of the fact that a great general knowledge is important, and we want people registered, but also that you might have a particular skill in a particular area, and that might be something you want to pursue.

On professional organisations

When I moved to Sydney from Newcastle, I didn’t know anyone. One way to get to know people was to join an Institute Committee. I did that – and people I met on that Institute Committee and at the Local Practice Network are people who I’m still very good friends with today. I’ve met so many people through that involvement and one thing has led to another and another, and some of them crossed over. This comes back to the idea of ‘designing your career’. I say to students that navigating your career is also about finding things you’re passionate about – whether it’s Emergency Architects or you want to be involved in a Digital Fabrication User Group. It’s finding your tribe and it will take you places. People start seeing you as a go-to, that you might know stuff others might want to know about. And you gain as much as you give.

Sometimes committees can be very draining, and some people can be very difficult. But you also start to learn about all the different types of people in the profession and how to get around and manoeuvre yourself. And it’s not about being political. It’s about understanding how the thing works. Unless you invest some time in that, you’re never going to know. People say to me, “How do you know everyone?” But a) I don’t, and b) That didn’t happen overnight. I came to Sydney and only knew five people – people I’d gone to uni with. It’s about investing time.

On setting up practice

I wanted to run my own practice from my first year in architecture as a student – and that small business ‘bug’ came from having grandparents who ran their own businesses. I had also worked as a music teacher and accompanist from the age of 15, so I was very used to invoicing people and dictating my terms, and managing myself and being my own boss.

I knew that I’d have to work for other people, but it was always my intention to run my own business. I did choose to work in practices where I felt I could learn things, that there was a good chance of not being stuck in the middle of documentation, and that I would gain exposure across the whole business.

For me, running my own business was about autonomy first and foremost. I’ll admit that I’m not very good at taking instructions from other people. After that period of six years, when I worked for other people, I felt like I was definitely capable and competent as a designer and as a fledgling business manager to set up on my own. I had a business partner at the time, and we were very quickly able to evolve our small part-time practice to a full-time thing for both of us. We had a number of early wins – getting them under our belt, getting them built, getting them published.

We found our first job through Archicentre, which back then was a fabulous, well-run thing. Once I became registered, I did the Archicentre training and very quickly was being sent concept design report commissions from them. We weren’t paid a lot, but the aim as hungry young practitioners was to do a great job and convert those concept design reports into ongoing clients and jobs. Pretty quickly we were building projects. The first one we built from an Archicentre lead was published in The Sydney Morning Herald. We were published in magazines. From 2004 onwards, we built the practice from there. We had that practice for nine years, and then I decided I wanted to do my own thing. I’ve had this practice Bijl Architecture for seven years now.

I needed the flexibility of having my own practice to maintain the level of professional involvement I wanted. And then when I had kids, the flexibility was about managing family life, which is still very relevant for me. My kids go to school across the road and this is their second home. I’m three minutes away from the school office when I’m walking slowly. We’re very fortunate that we’ve been able to stay in this office.

Bijl and street artist Ox King joined forces on a street art piece for TwoGood’s Felicity 2.0 campaign, highlighting issues related to gender equity and inequality. Bijl and the build team pictured. Photo: Edison Malones

On the benefits of mentoring

I’ve mentored for the Institute’s Mentoring Scheme with students, I’ve mentored with NAWIC and I was also a mentor for an architecture student through The Smith Family scholarship scheme, where a scholarship holder is paired with a professional in their field.

The mentoring really depends on what stage people are at. Through NAWIC I mentored a woman the same age as myself, who had decided after having her first child that she wanted more control over what she was doing and to start her own practice. So, she wanted mentoring around how to structure and manage a practice rather than mentoring around career. Student mentees often come with questions about what they’re doing at uni. They want to see the bigger picture. They want to know how to get a job, how to write a CV.

It was interesting mentoring someone through The Smith Family who had family struggles. It was about life advice as much as architectural career advice – and how these might fit together or not fit together. We would mostly chat over the phone, but I also tried to catch up with her once or twice a year in Newcastle, where she was based.

Regularity is important. Mentoring works best when people have a good space of time to reflect on their needs and to take onboard what you’re saying, but also to bring other things to the mentoring session.

I’ve also done a bit of professional mentoring – mentoring other practitioners who need practice advice. I mentored one guy for about a year and a half, and he was constantly being offered opportunities to go into partnerships, and he was asking, “Should I do it?” I’ve even been a bit of a phone-a-friend at times. This was formalised a year or so ago when the Institute’s National Practice Committee appointed me as a Senior Counsellor.

If I can be really pragmatic about it, one of the great things about mentoring is that you can claim it as CPD. Many practitioners get really hot under the collar about needing CPD for their registration, but CPD isn’t just about going to boring seminars burning time you ‘don’t have’. Activities like mentoring and interacting with others in the profession and examining can be used for your professional development. Those who haven’t mentored should consider it. You can claim informal CPD points, and with some mentoring programs I think you can claim formal CPD points for activities such as participating in a structured mentoring scheme with the Institute. Ultimately, the mentors get as much out of it as the mentees. You have to prepare for the sessions, drawing on your knowledge and learning about them, so there’s definitely professional development tied up in that. Mentoring is also a great way to influence the future profession. It’s not that I’ve got a God complex, but I think if you’re a capable practitioner, you should want to influence the future profession, because we’re not going to be around forever. I’d rather empower younger people and other practitioners to build a better profession, from which we ultimately all benefit.

In Sydney, the Institute has these small and medium size practice forums, where 20 to 30 Directors will get together and talk about challenges we’re all facing. And that’s been incredibly beneficial. You can feel the barriers between yourself and other people falling away, when you realise that we’re all sharing similar challenges, the same problems. We can learn from each other. It’s just a pity that we can’t do that beyond the scale of 20 or 30 people. I feel like we need more of these groups.

It’s good to have friendly and supportive competitiveness. If you don’t win the job, then you’re glad for the person who did win it, because they’re an architect, and hopefully they’re a good architect. Mentoring helps to build networks too. People ask me why I have to recuse myself from examining so many candidates, and it’s because I’ve either taught them or mentored them or been on a committee with them. It’s because I’ve tried to expand my networks in all directions – not just with people my own age. It’s important to have vertical and horizontal networks, being part of the broader profession.

On personal achievements and ongoing missions

I’m happy I’ve been able to make a positive contribution to the profession, which needs people who are leaders but aren’t just leading through design. My practice does do some nice projects. We get some nice things published. That’s great. And I don’t think I could call myself an architect if I wasn’t having that creative output working with different clients. I think I’ve been able to capture a certain body of knowledge and be someone who can see a way forward in how we as a profession can be better, can do better. I don’t think that work is finished at all. It’s only just begun. It takes a long time to galvanise people. It takes a while to crystallise that knowledge where you can see a way forward.

I’m someone who sees a framework and sees opportunity, rather than restriction. For example, some people see the competency standards as limiting and that everyone has to have a traditional career in order to be a registered architect. But we’re not saying that at all. We’re saying that we want people to be able to tick a certain number of the boxes, pass an exam, and then they can call themselves a registered architect. I see the framework as being able to enable people to do things and an opportunity to find expanding boundaries. A framework can be a place where we find new areas to explore; it’s not just a place of restriction.

It’s one of my missions to try to get others to think differently about how we deal with having frameworks. How do we balance frameworks and opportunity? For example, national mutual recognition is one of my goals. The fact I’ve got three numbers listed after my name to indicate I’m registered in NSW, Victoria and Tasmania is ridiculous. We would be a better profession, we would make better representations on a federal level if we were unified as a national body. But we’re not. Because we have all these individual states. Something I’m very passionate about is trying to find a way to structure ourselves where we can make better representation to government, to industry, to community.

On advice to your younger self

I would advise my younger self to say no earlier – and more often.

Like a lot of women, I have felt the need to please others from very early on. And the way I learned to please others was doing well – doing well at school, doing well at music. It wasn’t my parents doing the pushing. My mother says I was always self-driven. But saying no has always been very difficult for me. I’ve always been worried about offending people. I don’t want to give people a reason to think badly of me. That is one of my fears. It doesn’t mean that I want to be friends with everyone. I’m realistic about that. But it does mean I struggle to say no.

There are probably all sorts of things I should have said no to. I should have said no to my previous business partnership well before I did. I should have said no to all those weekend and after-hours meetings. I did it for a while, but then I started questioning it. I thought: These people wouldn’t ask their accountant to come and sit on their couch for two hours on a Saturday afternoon. Why should I? I do really feel for architects who don’t have children or have an easy excuse to use, who are constantly pressured for a meeting at 7pm at night. As time went on, I started insisting on business hours only. And I wish I’d done it earlier. I actually believe that if we’d done this earlier, we would have weeded out some pretty awful clients over time, who had all sorts of requests. At the end of the day, people with unreasonable requests are usually unreasonable people.

Again, when you’re running a practice, a difficult client isn’t just affecting you – it’s your staff as well. It can have a very unhealthy effect on them, their work and their enjoyment of the job. We are certainly a happier, healthier practice since we started saying no.

Bijl Architecture’s Doorzien House in Kirribilli. Photo: Katherine Lu

Melonie Bayl-Smith is Director and Founder of Bijl Architecture and Adjunct Professor at the UTS School of Architecture. An elected member of the NSW Architects Registration Board (2017–2020), she was also an elected member of the Australian Institute of Architects NSW Chapter Council (2015–2017). She is the NSW State Convenor of Pathways for the AACA and ARB NSW, a member of the Institute’s National Gender Equity Committee, and a Fellow of the Australian Institute of Architects (FRAIA). In 2018, Melonie was the recipient of the Paula Whitman Leadership in Gender Equity Prize.

As a member of Women on Boards, Melonie has advocated for improving women’s representation on boards by regularly speaking on this at various industry and non-industry events. Melonie has been involved with the National Association of Women in Construction (NAWIC) since 2005, where she has been an active contributor through mentoring. In 2010 she received the NAWIC International Women’s Day travelling scholarship for her BuildAbility research project, also awarded a Byera Hadley Travelling Scholarship, which investigated the future of construction education in architecture schools across Australasia and internationally.