How do recent anthologies of architectural theory represent feminism and gender theory? Karen Burns’ essay “A Girl’s Own Adventure: Gender in the Contemporary Architectural Theory Anthology” surveys seven such anthologies. She finds only six essays over the seven publications and concludes that this thin coverage, together with the editorial framing of the texts, results in a “strangely antiquated”, essentialist version of feminism that is at odds with the aims and content of much of the work.

The essay has just been published in the March 2012 issue of Journal of Architectural Education 65, no 2, pp. 125–134. We present an earlier version of it.

Woman is always . . . that which calls out to Man, that which puts him into question.1

Gender/genre

Since the late 1980s the architectural history survey course and its companion – the history survey text – have been scrutinized for their gendered assumptions.2 Less heat has been turned upon the theory anthology, a new genre of text and course reader emerging in the mid 1990s. This essay examines seven major survey anthologies from the recent fin-de-siècle to explore the place of feminist and gender discourse within the architectural theory revolution. How do “feminism and gender theory figure in these anthologies, many of which survey the period 1968 – 1995 and the 2000s, years spanning the emergence and consolidation of women’s rights, feminist activism and feminist theory? In an issue of JAE devoted to beginnings and origins the surveys provide a place for studying how the discipline of architectural theory has begun to assimilate sexual difference, or change after its encounter with gender theory.

Even as architectural theory anthologies record theory’s transformative force within the discipline, the genre of the anthology text arrives with instruments and methods that can undermine good intentions for disciplinary critique.3 By defining borders, staking territory and producing surveys, anthologies construct a canon, a disciplinary space ordered by collection, classification and exclusion.4 Moreover despite the discipline’s critique of survey methodology, through recourse to chronologies, opening and closing dates and organization by linear time, theory collections can function as good old-fashioned survey texts.5 Like all texts, their representations are partial, marked by omissions or elisions and a “way of seeing” that frames the material they work on. Studied collectively, these anthologies produce a strangely antiquated portrait of gender and feminist practice. They reshape a complex body of gender theory within the reference points of body, biology and sexuality. This portrait is arguably essentialist, a term that feminists use to describe attributions of “a fixed essence” to women.6

Survey

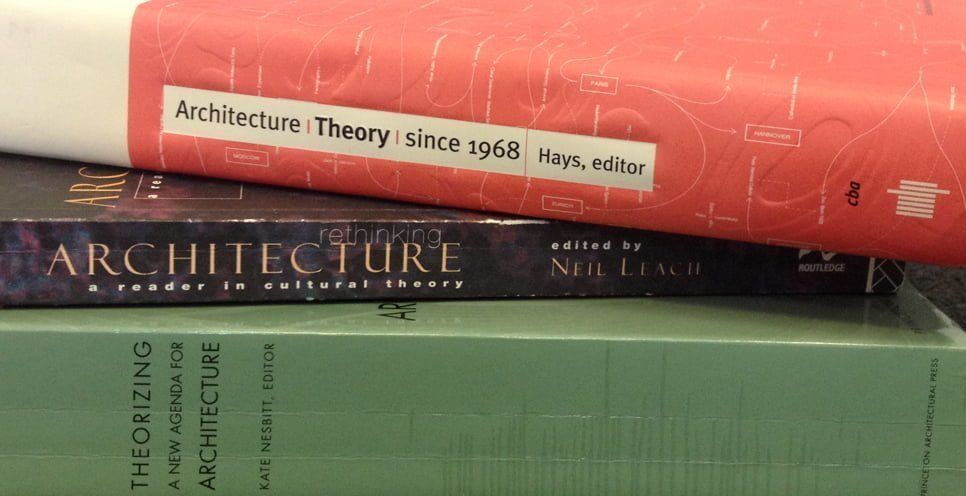

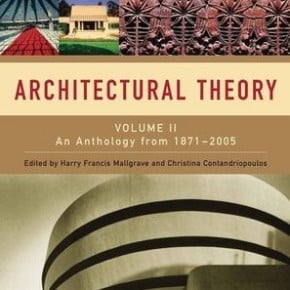

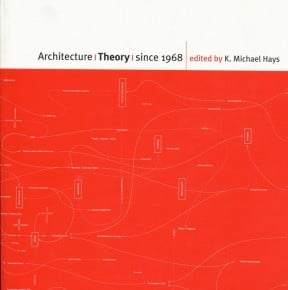

The seven theory anthologies examined for this study are formally varied and differently historically situated. Only one collection provides a historical survey of a centennial period, Mallgrave’s Architectural Theory: Volume II, covering the years 1871 – 2005. Another text, Stein and Spreckelmeyer’s Classic Readings in Architecture, selects canonical readings from the long durée of architectural theory production beginning with Vitruvius as theory’s founding father. Three other anthologies form the most common type: Kate Nesbitt’s Theorizing a New Agenda for Architecture, K. Michael Hays’ Architecture Theory Since 1968 and Charles Jencks’ Theories and Manifestoes of Contemporary Architecture. These three books document the rise of theory in the late twentieth-century. Each collection nominates a different moment for the “birth” of theory, identifying it as a post-war phenomenon or a mid 1960s or 1968 event. The theory genre was formally recognized by the update to these anthologies: A. Krista Sykes’ 2010 work, Constructing A New Agenda: Architectural Theory 1993-2009. Finally, one text was both a part of this set and a variation to the genre. Neil Leach’s anthology Rethinking Architecture is a companion piece to twentieth-century architectural culture. His chosen theorists are influences, contextual voices and occasional participants in architecture rather than recognizably architectural actors. Nevertheless despite these differing aims and forms, the seven texts display remarkable coherence around the minor status, homogeneity of representation, and absence or slight representation of feminist and gender work in their pages.

Reading the seven anthologies with an ear to sexual difference has been a dispiriting exercise. Feminist and gender work is excluded entirely from the 1871 to 2005 period covered by Mallgrave’s historical survey. Those poor suffragettes who opened the twentieth century by chaining themselves to buildings will be turning in their graves. Sexual difference studies are also completely absent from the other end of the century in the most recent Sykes’ publication covering theory from 1993 to 2009. Three of the architectural collections and Leach’s anthology anthologize one gender essay each.7 Only Stein and Spreckelmeyer’s anthology has a generous selection practice by including two gender essays. In total, four of the six architectural anthologies and Leach’s cultural anthology include feminist work, a haul of six essays from seven books. Sexual difference and feminism have celebrity slim page weights in the theory anthologies.

On one level my complaint is a familiar grievance about proportional representation.8 The three most recently published collections could have searched material by consulting the eight and a half page bibliography on gender, space and architecture writings produced from the 1970s to 2000, easily available in a Routledge publication Gender Space Architecture (2000).9 But the problem of size (size matters for feminists) creates compounding issues of selection and representation as complex discourses are compressed or absent. Minor anthologisation produces three elisions in representations of feminist discourse. The texts suppress generational difference, diversity of content and differences between feminists. These elisions shape the portrait of feminism’s interests as fixed and essential attributes of women and gender scholarship.

Plus ça change

Generational differences between feminist scholars are one marker of the dynamic of historical change within feminism. Awareness of generational difference provides a way of notating differences between feminists, tracing the reflexivity of feminism as its practice/theory responds to new conditions, and as it produces a critique of its own operating premises. Feminist concerns may appear identical across time, but closer inspection reveals the unfamiliar in the apparently identical.10 What appears to be an enduring, ahistorical feminist interest, such as the “body” possesses a particular historical texture. The category has shifting contours and may be renewed, repudiated or rewritten by different feminist practices, as we shall see later in this essay.

Feminism’s transformation over time is generally elided in the selection and editorial framing provided by each individual anthology although when four architectural anthologies are studied collectively, two generations of gender studies are represented. The Stein and Spreckelmeyer collection anthologises a 1974 Claire Cooper Marcus essay “The House as Symbol of Self” and a 1984 Dolores Hayden essay, “Placemaking, Preservation and Urban History”. The Jencks and Kropf collection anthologises two pages from Dolores Hayden’s 1980 essay “What Would a Non-Sexist City Be like?”. These two collections with their essays by Dolores Hayden and Claire Cooper Marcus suggest something of the scholarship that proceeded post-structuralism.

Feminist architectural post-structuralist work is represented in two of the architectural collections with a Diana Agrest text anthologised in Nesbitt’s book, and an essay by Jennifer Bloomer reproduced in the Hays’ collection. Neil Leach’s cultural anthology includes one essay by Hélène Cixous. In Architecture Theory Since 1968, K. Michael Hays distinguishes between earlier and 1980s feminist practice. His remarks are a rare instance of historicisation. However taking each collection individually, a reader would be at a loss to engage with the changing generations of feminist scholarship from 1977 to 2010. Jencks/Kropf and Stein/Spreckelmeyer only represent scholarship from the first generation from 1977-1984, and not from the second generation of post-structuralist work emerging from 1984 onwards, whilst the Hays and Nesbitt collections only deal with one essay each from the second generation. The third generation is entirely absent, although it emerged around 1995. It is dominated by British and European work in materiality, performativity and the ethics of human relationships. This third formation is not represented in the 2006 anthologies of Mallgrave/Contandriopoulos and Jencks/Kropf, or the 2010 Sykes’ collection. Each generation of scholarship uses different methodologies and a differing focus. There are of course broad continuities but feminist scholarship produces its own internal critique and responds to changing social and philosophical conditions.

Generational change entails broader changes in content and methodology but there is, arguably, a narrow compass of topic areas overall in the collections. In two of the anthologies, the one edited by Nesbitt, the other by Hays, feminist work is aligned with the body. In the Stein and Spreckelmeyer canonical collection gender studies is associated with minority identities and with corporeality and the domestic. (See one essay each by Claire Cooper Marcus and Dolores Hayden). A long urban discourse has exiled the feminized home from the masculine city, a topic explored by Dolores Hayden’s argument for a third space, an inclusively planned neighbourhood, in her essay “What Would a Non-Sexist City Be Like?” anthologized by a two page extract in the Jencks collection. Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley, two authors central to architectural gender studies at the turn of the 1990s are represented in the Hays’ anthology, but not by essays analyzing sexual difference.

After noting these contributions, one closes the pages of seven anthologies and is left with the impression of sexual difference scholarship as a fairly hard worn path in the familiar topography of the domestic, the corporeal and axes of difference.11 My grim categorisation is not intended to denigrate the fine scholarship of the individual authors but rather to suggest emerging patterns across the set of anthologies. These form what Foucault’s describes as the “statement” function in a discourse: what is said about something, rather than what the something says.12

A primary text moves from its initial origins as it enters the anthology system. As a newly collected artifact the text no longer only represents its original material but assumes exemplary status as a representative of the “context” it has left behind. Editorial transformation occurs in this gap. Understanding how ”gender” texts are chosen and why is difficult to diagnose since most of the anthologized essays don’t address their gender selection criteria. Only two anthologies provide editorial remarks that address the substance of feminist and gender discourse, in the editorial framing of a Diana Agrest essay selected for the Kate Nesbitt anthology and in the framing of a Jennifer Bloomer text selected for the K. Michael Hays’ anthology. In these two instances the editors step out of their editorial masks to become reader/authors, paraphrasing and contextualizing the texts. Placing their framing remarks beside the primary texts helps us see the anthology’s mechanisms of transformation. These changes allow us to understand how, by small, incremental gestures, a particular image of feminism emerges from the anthology pages.

Girl Talk

Discussing the Nesbitt/Agrest and Hays/Bloomer remarks as a way of exploring the transformations undergone by the feminist text in the anthology system is useful but feels a little mean spirited. Both editors appear sympathetic to feminism and their editorial glosses are largely sophisticated. But the cultural unconscious of a discipline writes on individual editors even as they write upon it. Both editors supplement their framing remarks with references to the woman theorist’s body as a primary site of explanation for feminism or the locus of feminism’s resistance. Aligning Bloomer and Agrest’s own bodies with their critique, radically curtails the strategies and applicability of post-structuralist feminism, realigning it with a body and biography centred practice.

In Kate Nesbitt’s anthology, Theorizing a New Agenda for Architecture: An Anthology of Architectural Theory 1965–1995 (1996), feminism (and as we’ll see gender) appears within a larger class titled “Feminism, Architecture and the Problem of the Body” with entries by Bernard Tschumi, Peter Eisenman and Diana Agrest. The inclusion of essays by Tschumi and Eisenman is a generously eclectic application of the term feminist to two regular guys but Nesbitt’s category implicitly touches on the relationship between feminist interests and broader theoretical currents. Yoking Agrest, Eisenman and Tschumi together produces a contextual frame and the list of proper names suggests that feminism and the body will be the shared province of male and female theorists.

However, the shared project of the body and feminism is not discussed because Nesbitt provides introductory remarks for each essay rather than situating the three in a relationship. Only Agrest’s essay explicitly addresses the social production of a gendered body. Certainly Tschumi and Eisenman’s topics – the former dealing with desire and transgression, the latter providing a critique of occularcentrism – are well within the feminist orbit. Neither explicitly gender the practices they discuss although Tschumi uses the definite articles “his and her” at one point in his essay. This un-gendered space contrasts with Agrest’s piece, a subject worthy of editorial comment. Although the category heading of the anthology deals with “the body”, Agrest’s essay frequently undermines the neutered corporeality of “the body” as she studies the production of an idealized male body and a displaced maternal, female body.

Agrest’s’ 1971-1987 essay “Architecture from Without: Body, Logic, and Sex”, is divided into two parts and the first part offers a historical and theoretical analysis of systems of gender in the works of Vitruvius, Alberti and Filarete.13 Most of her essay is devoted to the emergence in architectural discourse of an idealized male body at the expense of an un-idealized female corporeality, a transformation effected by an “elaborate mechanism of symbolic appropriation of the female body” that underpins the emergence of Man’s body at the centre of Western classicism.14 A number of substitutions feminise the architect; powers of reproduction are conferred upon him and his navel replaces the umbilical cord. The masculine body’s desire and power – symbolized by the phallus – produces knowledge systems. By Agrest’s account mechanisms of appropriation, substitution and repression form knowledge and constitute it modes of understanding. As she observes, “That repressed, that interior representation in the system of architecture that determines an outside (of repression) is woman and woman’s body.”15 Inside and outside, included and excluded, acknowledged and repressed, are, part of the same system. This system genders terms and systems that recognize, classify and certify what counts as knowledge and what counts as an architect.

Nesbitt’s introduction successfully glosses the first part of the essay but she moves into more perilous terrain when she describes Agrest’s aims. Here she expands her remit to include allusions to Agrest’s personal experience. Nesbitt observes:

The goal of Agrest’s critique is the recuperation of the female body in architecture. As a female architect, she has experienced the exclusion of the ‘system’. She suggests in the introduction to her collection of theory essays that an outside position may be an advantage given her goal:

It is from without that one can take a true critical distance. Outside means from the city, from other fields, from other cultural and representational systems.16

In “Architecture From Without” and the introduction she writes to a 1991 collection of her essays, Agrest clarifies the nature of this “outside”. Architecture’s exterior is not sited in herself Diana Agrest, or in a female body or in a female architect, “It is from the city (the unconscious of architecture), from outside, that critical work on architecture is developed.”17

In her book introduction and in part two of her “Architecture From Without” essay, Agrest represents the city as heterogeneous and fragmentary. It cannot provide a mirror reflection of a system of architectural rules or an architectural body constructed as whole, total, formed, autonomous and closed. Moreover it produces a different kind of architectural subjectivity. Agrest describes herself as a “reader-writer”, tracing the complex exchanges between city and self, “ I am spoken through the city and the city is read through me.”16 I differ sharply from Nesbitt in describing Agrest’s goal, mode of identity, agency and outside space. I am worried that Nesbitt links the female “body” (an entity distinctly different from Agrest’s “fragmented body”) to the woman theorist and the woman theorist’s personal experiences when Agrest does not describe herself at all in these terms. Nesbitt moves us from a critique of disciplinary knowledge systems to Agrest’s gender, biography and otherness as the site of resistance.

Other problems ensue from the anthology’s framing. Firstly Agrest moves from a feminist analysis to the production of a critical subjectivity (the reader-writer) and space of exteriority (the city) that provide general terms to rethink critical practice. Her work has wide spread application beyond feminist practice. Feminism’s varied research areas and wider impact are curtailed by the reduction of its geography to: the woman’s body, the personal, the biographical and the female signature of writers. Including gender analyses by male writers such as Mark Wigley’s “Untitled: the Housing of Gender”, a critique of Albertian discourse, would have transformed the feminist project into a set of critical practices independent of the gendered signature of the author.18 If a male imaginary body serves as the invisible norm for architecture’s discourse, a frequent charge of feminist architectural theorists, marking women as signs of “the Body” masks and reinforces the masculine foundation of architecture.19 Gender can appear to only be a property of women.

If Agrest’s essay is concerned with what is repressed, feminism’s assignment to the “body” category effects a kind of repression of its topic areas, impact and agility. Feminist essays could have appeared in the other category topics of Nesbitt’s anthology such as “Postmodernism”, “Postructuralism”, “Urban Theory after Modernism” and “Political and Ethical Agendas”. Nesbitt’s editorial category organizes relationships of interior and exterior. Feminism is not granted the same degree of mobility as Tschumi and Eisenman’s practices, which are anthologised multiple times across several categories.20 The body is not a category that feminism can escape from but the body need not confine feminism to a singular space.

Nesbitt’s alignment of the woman’s body and the biographical as the magnetic poles of feminism might be dismissed as an effect of an idiosyncratic editorial gloss. However the only other editorial commentary on feminist practice provided by an anthology editor – K. Michael Hays’ framing of Jennifer Bloomer’s “Abodes of Theory and Flesh: Tabbles of Bower” essay – performs a similar marking of the woman theorist’s body as a site for feminist practice and the locus of feminist resistance.21

Ornament

Bloomer’s essay comes well towards the end of the 1980s roll-call which dominates the Hays’ anthology. Of all the anthology editors Hays is the most impressive in contextualizing and glossing the feminist project. He introduces Bloomer’s essay by contrasting her generation with an earlier feminist theory project concerned with correcting the records or writing women in to texts, countering their absence from official history. This is not the only way to describe an earlier methodology but it’s not a bad start.

Introducing Bloomer, Hays identifies a new 1980s feminist project concerned with critiquing the “phallocentric codes of analysis”, interrogating terms such as production, rationality, objectivity and dualisms. He situates Bloomer’s text at the intersection of feminism, architectural theory, deconstruction, psychoanalysis and literary theory. This successful, sophisticated framing is then followed by a more specific definition of the new feminist turn. He notes that the “phallocentric codes of analysis and production . . . posit the feminine as that condition which is always already repressed, misrepresented and violated in the very structure of architectural thought.”22 He observes that Bloomer calls for a minor architecture feminine following the model of l’écriture féminine. Hays transposes a term – feminine writing – from Anglophone accounts of French literary theory, and manufactures a new architectural term. Bloomer’s task in the Hays’ anthology is partly to represent architecture feminine.

An attentive reader might notice the gap between the editorial classification and Bloomer’s stated intent. After three introductory quotations her own first paragraph declares:

Preface: To Bring forth allegory as a construct for theory is to point to a deconstruction of theory itself, and particularly, to a disacknowledgment of the separability of theory and practice. Theory and practice are suspended in the construction; theory is embedded or disseminated, in it. . . .23

She does not call for an “architecture feminine” or ever use this term in the essay. Instead she rewrites assumptions about the theory and practice pair, conducting this investigation through a series of complex intersections between anecdotal observations, case studies, texts and works, all centered around the ornament structure coupling. Understanding how this pair is often related to another critical couple – male and female – Bloomer quotes the feminist proposition that ornament has often been negatively associated with femininity. Nevertheless Bloomer recuperates the terms, transforming ornament and femininity into “a metaphor for many forms of alterity to the dominant.”24 Her installation/architectural project is a series of barnacle like corner structures, a sort of Louis Sullivan revenge on the architectural historians who treat his sexuality as a form of otherness or alterity. By composing a physical work she uses practice to confound the theory/practice binary, rewriting their conventional relation. Like the barnacle, her structures are habitable and parasitical, an allegorical gloss on the conventional understanding of the role of theory as handmaiden to architectural design.

Two more personal references to Jennifer Bloomer appear in Hays’ introduction. The opening lines and closing lines of Bloomer’s essay note the parallel gestation of the work and Bloomer’s pregnancy, constituting some thirty lines in all. Pregnancy and birth are used to critique conventional parallels with conventional building production that depict the architectural product as the ordered and whole outcome of an “uncertain period of gestation”. Bloomer counters with all the other ‘abject” things discharged during birth. She contaminates architecture’s story of its buildings as autonomous, unified and clean.

When the piece was first published in Assemblage Bloomer in part repudiated the structuring metaphor, observing that it was in an important sense, “inappropriate” because the “hermetic” and “private” enterprise of child bearing was different to the “collaborative’ nature of the project described in the essay.25 Nevertheless Hays mentions Bloomer’s pregnancy and childbirth in quite different terms, noting, “pregnancy is prior to the separation of self and the other . . . and cannot be presided over by the male gaze”. In rewriting women’s particular bodily experience (or sexual difference) as a site of resistance to the “male gaze” Hays reduces Bloomer’s disciplinary knowledge critique to a separatist, other space that excludes men.26 Finally I note that he further describes Bloomer’s own body by observing that her texts “achieve another level of emotional and epistemological significance when she performs them in public”. However Bloomer’s recourse to quotations and alternating voices and genres is a standard post-structuralist tactic.27

Whilst paraphrase is a useful writing device and probably an editorial necessity when writing anthology introductions, paraphrase runs the risk of losing its mirror function: its ability to reflect the text it describes. Of course no gloss can be a truthful account of the text it represents, but an editor’s glosses are interpretations and symptoms of a reading position. I am going to write in Hays’ margins by returning Bloomer’s own voice to the discussion, along with other feminist voices from the turn of the 1990s. If the anthology system asks a text to be exemplary of the context it leaves behind, designating the Bloomer text as an exponent of “architecture feminine” brings double trouble. As we’ll see she never used this term and the “feminine” was an important, contested concept in the later 1980s and into the 1990s. Moreover, it was the shared, if disputed, property of men, women and architecture.

Feminine/feminist

In her 1993 book Architecture and the Text. Bloomer declaimed, “I write the feminine”. In so doing she wrote in the tracks of Hélène Cixous, the French author most closely identified with the term l’écriture féminine. But Bloomer coupled writing and not architecture to the feminine and her declaration must be taken against another epigram from the same text: “A feminist architecture is not architecture at all” suggesting that the two terms cannot be thought together.28 This is a double movement. Architecture constructs its identity through the exclusion and repression of feminism, but the terms which feminism uses to construct spatial practice fall outside the boundaries of a category called Architecture. (Hays quotes Bloomer’s sentence in his remarks, introducing it as “the fearful threat of feminism to architecture and theory as traditionally practiced is perhaps put by Bloomer herself”.”)29 A 1993 letter written by Jennifer Bloomer and published at the beginning of the Any issue “Architecture and the Feminine”, unravels her relation to these troublesome words, noting the “intersection of the feminine and the feminist”. She then observes,” I despair that so many find these terms of identity … “I don’t expect there is an easy, or perhaps even fruitful, delineation of the relation between them.30

Bloomer’s work is a critical investigation of the problem of the terms’ relations. She settles on a conjunction (Architecture and …) not the seamless identity of a noun /adjective (architecture feminine). She comments explicitly on the difficult feminist appropriation of the term “feminine” in order to dislodge it from its phallocentric labour:

The metaphor of the feminine is a ‘gift’ bestowed by the male upon the female that is then taken back and bestowed upon the object . . . this troping of the feminine creates a slimy mess . . . a paralyzing quagmire for women who make objects.31

The phrase l’écriture féminine remains a contested concept within feminist discourse. For some writers the phrase is an Anglophone term arbitrarily conferred on French writers Luce Irigrary, Julia Kristeva and Hélène Cixous, with only the latter self-identifying with the term. Debates over the feminine are embroiled in disagreements over the value of political strategies that reclaim and rewrite derogatory or disabling descriptions of women. These exchanges are haunted by the spectre of the failure of feminist re-writing. Thus the term’s new feminine /feminist empowerment may be missed. Or a writer who speaks in the name of the feminine might echo familiar stereotypes for inattentive readers, sending the feminine into orbit amongst essentialist and sexist signs. This anxiety and ambivalence drives the vexed exchange between Cynthia Davidson, Anne Bergren and Jennifer Bloomer at a 1993 symposia, transcribed in the opening pages of the 1994 Any issue “Architecture and the Feminine”.

For some, the ”feminine” is too contaminated, too dangerous to be successfully recuperated as Davidson observes,

I am struggling with the place of the feminine myself.? . . . What is it about discussion of the feminine in architecture that for many women still feels like a ghettoization of a cultural issue? . . . where in architecture does the feminine find its site?32

Not surprisingly some of the anthology editors also found themselves on the treacherous ground of sinking meaning. Including the Davidson/Bergren/Bloomer correspondence in one of these anthologies would have allowed readers to enter a debate about the category of the feminine and its fluidity. As Cixous observes, “It’s impossible to define a practice of feminine writing”.33 She suggests that it is process and not an identifiable style or category. The term gazes towards a future horizon less entombed by past debris. For feminists l’écriture féminine does not represent the misrepresented, violated and oppressed but glimpses a future inhabited by women’s voices not yet heard or spoken in their own tongues. It is an incantation and performance to call something new into being. (We might also call this creativity.) This is Bloomer’s point and Davidson’s anxiety. Understanding these terms requires editors and readers to be attentive to the differences in texts and between texts, to more careful theories and practices of writing and reading. The term “feminine” escapes architecture’s commitment to visible form as a marker of difference.

The feminine is aligned with Bloomer and corporeality in the Hays’ anthology but this alignment might also be understood within the terms identified by Diana Agrest. She examines architecture’s appropriation of the body of woman, replacing her with masculine others, thus displacing her to the outside. Bloomer’s survival as the solitary exponent of architecture feminine becomes even stranger if we briefly detour to the archives for documents on the feminine’s appropriation by mainstream architectural “avant-garde” concerns in the late 1980s. My irritated scribblings in the margins of the anthologies take me beyond the remit of a “review”, as I pursue a classic feminist strategy of writing certain exclusions back in. Bloomer’s emergence as architecture feminine in the Hays’ anthology effects another very important repression in the representation of late 1980s and early 1990s theory. Her inclusion masks the masculine possession of the “feminine” as a radical theory and design tactic.

Women, Men and Architecture

When Hays’ frames Bloomer’s work he alludes to the utopian potential of the l’écriture féminine writing mode and notes, as does another anthology editor Neil Leach, that the term does not only refer to women’s writing.34 The easy conflation of l’écriture feminine with the feminist and woman Jennifer Bloomer (or Cixous) would have collapsed if this observation had been more fully pursused: l’écriture féminine is not necessarily a property of women although it is often assigned to their bodies. Expanding this observation might answer Davidson’s qualms about the feminine as a ghettoizing term for women. Bloomer follows in the tracks of Hélène Cixous by tracing intimations of feminine writing in the texts of well-known French philosopher Jacques Derrida.35 Cixous describes Derrida’s writing as “feminine writing”.36

Derrida was central to exchanges between architecture and philosophy from 1984 to 1992 and beyond. His most visible architectural partnership with Peter Eisenman is memorialized in the Neil Leach’s anthology Rethinking Architecture by the selection of Derrida’s ironically titled 1986 essay, “Why Peter Eisenman Writes Such Good Books.” The essay chiefly concerned their collaboration at Parc de la Villette known as Choral Works. The project was fertilised by Derrida’s reading of the foundation myth of the universe narrated in the opening pages of Plato’s Timaeus text. Plato’s account of the birth of the cosmos describes the cosmos as a changing copy of a perfect, eternal model. The entry of a third term – chora – enables Plato to resolve the paradox of reconciling change and the eternal, the original and the copy. Chora is the active agent of transformation and becoming. Chora is gendered feminine as womb or lyre or matrix or winnowing sieve.

Derrida’s texts retain traces of l’écriture féminine and his writings follow the path of the feminine in philosophy, an insight that could be used to editorially frame Derrida’s Eisenman essay and the centrality of chora in their collaboration. Instead Leach’s introduction focuses on the architect/ philosopher coupling, as Leach observes, “the work was not based on a division of labour whereby Eisenman supplied the architectural forms, and Derrida the discourse. Rather it was a process of collaboration… “.37 His remarks about feminine writing as a product of both male and female authors were confined to his introductory words on the Cixous essay. However, if Leach had produced an alignment between Derrida and the metaphor of the feminine he would have enabled readers to sense some of the important historical exchanges between feminism, architecture and post-structuralism.

Feminists describe phallocentrism as the use of a singular masculine model (hence the sign of the phallus) to describe two sexes. In this model women or the feminine are facsimiles or inversions of the masculine but never different in their own way. Post-structuralism’s famous critique of western metaphysics produced the neologism, “logocentrism”. This term refers to the tracing, notating and prying apart of the authority of the word, voice and self in philosophy, terms central to the consolidation of masculine power. These interleavings allow the writer Gayatri Spivak to claim that “the contribution of post-structuralism to feminism is the critique of phallocentrism itself.38 But the relationship also travels in the other direction: feminist work inflects post-structuralism. As Spivak formulates the relation, the “historical state of becoming woman is something that post-structuralism has tried to appropriate a little in order to articulate for itself a space that is not phallocentric”.39 “Becoming woman” is the metaphor for mobility, for fractures, cracks and movement opening up interstices within the foundations of philosophy’s traditional ground.

Margin/mainstream

Both the Nesbitt and Hays’ anthologies touch but don’t elaborate the knots of feminism and post-structuralism. The segregation of architectural feminist theory from the sections on post-structuralism in the anthologies makes it harder to grasp these mutual dependencies. Reformulating Spivak we could observe that in order to fulfill its critique of logocentricism, architectural post-structuralism had to make new spaces for itself outside phallocentric space. This insistent turn to the state of becoming woman enabled Peter Eisenman to read Plato differently in his Chora project. Although he may not have realized that this was what he was agreeing to when he assented to a rendezvous with Derrida at Parc de la Villette.40

A number of feminists maintain productive relations with post-structuralism’s tactics whilst remaining acutely conscious of its reliance on the metaphorical condition of Woman. Elizabeth Grosz notes the ways in which chora achieves this metaphorization of the feminine in both Derrida and Plato (and I would add Eisenman):

. . . the silencing and endless metaphorization of femininity as the condition for men’s self-representation and cultural production . . . their philosophical models and frameworks depend on the resources and characteristics of a femininity divested of its connections with the Female (especially with the maternal) body and made to carry the burden of what men cannot explain, articulate or know … 41

In the early 1990s the analysis of chora by Grosz, Anne Bergren and others catalysed architectural discussions on the important but problematic relationship between feminist theory, feminist post-structuralism and post-structuralism. These chora essays could have been usefully anthologised to tease out the exchanges, critical frictions and feminist dismay that chora had been appropriated to enact a phallocentric agenda.

The brief inclusion of feminist work and gender studies in all of the anthologies surveyed makes it difficult for the reader to know that different positions and definitions characterise architectural sexual difference theory and their relations to other bodies of theory. But as the Agrest essay anthologised by Nesbitt argues, exclusions are as important as inclusions in analysing the dynamics of a discourse.

Visible Differences

Do the anthologies unconsciously ask feminism to perform a familiar role? Do they attempt to neutralise the feminist project of critiquing and struggling against the position of the Other by recuperating otherness as the property of women in these collections? Are female gender writers allocated the body as their primary topic “because (the body is) the most visible difference between men and women.”?42 If feminist and gender work is framed as an investigation into corporeality, feminism can be easily cast within the reference points of body, biology and biography. Although these are undoubtedly important sites for feminist research they can appear to be identical with an earlier form of feminist practice associated with 1970s women artists who used their own bodies as the subject of research and staged resistance in their own bodies. This practice was both lauded and criticized by contemporaries but I wonder it the ghost of 1970s feminist art practice is the stereotype reached for when we imagine gender work?43

Perhaps the problem is the anthology genre rather than the gendering of the architectural anthology? But although anthologies compress volumes of primary material, diversity and editorial voice need not be elided. The “Cultural Studies” reader discusses the problem of the canon and features quarrelsome exchanges between Cultural Studies heavyweights disagreeing over terms, definitions and the politics of practice.44 Section editors can bring expertise to each division of a theory anthology, outlining some of the main themes and debates in a topic area. The genre of “companion” guides to historical fields operate with many editors and draw on legions of experts to represent the complexity of topic areas. Different voices unpick the bindings and tight stitching of the solitary or senior editor. The gender theory failure of the architectural theory anthologies might be an architectural theory disciplinary phenomenon rather than the failure of the anthology genre per se to represent diversity.

This essay has traced significant elisions of gender debate, generational difference and subject matter to argue that the complex, variegated terrain of feminist and gender work is remapped as a small, familiar territory in the architectural theory anthologies. Selection produces significant gaps and absences but when these omissions are allied to editorial framing, the collections risk producing feminist theory as fixed and unchanging, a constellation of body, biography and biology. Essentialist material appears cut off from historical change and easily sealed within its own purpose built house. If gender studies interests appear identical over time it is easy to marginalise the material from the shifting ground of the theory mainstream. In this way it becomes perpetually Other to architectural theory even as it ostensibly remains a part of the field. Itts subject matter is perpetual rather than current.

The anthology selections produce an equally powerful effect: constructing women as the sign of gender and sexuality. The surveys risk a double essentialism: constructing the male architect as other to women’s otherness. If Agrest’s essay identifies how classical discourse produces the architect as a masculine, rational subject but her insight is not applied to the on-going construction of theory knowledge or if the anthologies elide male philosophers and architects’ dependency on the metaphor of the feminine in the 1980s and 90s, the anthologies enable the discipline to invisibly reproduce gender binaries. Consciously or unconsciously the collections reinstate gender, sex and sexuality as the domain of women: girl talk.

Architecture’s reading and representation of feminism has material effects: it shapes the discipline’s interior and exterior territories. Moreover when theory anthologies are assigned to architectural students as part of their study, the anthology contributes to shaping architectural subjectivity. Remembering Agrest’s injunction that architecture’s territories are produced through repression, we see the gap between the multiple subject matters inside the essays and their editorial frame. The theory survey relies on an old-fashioned methodology of taxonomy and classification but the multiple content of the feminist essay resists this kind of systematisation. However the transformative methodologies within individual anthologised essays can transgress their frames and spark questions about how the collections actively construct new territories of architecture’s inside and outside. The anthologies fold, break and turn differently in this space between the primary and secondary text. Dissent is the murmuring of different voices.45

Acknowledgements: This paper was originally written for the Society of Architectural Historians’ panel session on “Gender and Sexuality” at the Society’s 2011 meeting in New Orleans. The panel convenors – Victoria Rosner and Wanda Burbriski – generously but rigorously shaped this paper and I thank them. I would also like to thank Despina Stratigakos and Gabrielle Esperdy for supporting this work.

- Alice Jardine, Gynesis: Configurations of Women and Modernity (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1985), p. 183. I have inserted the ellipsis. The original reads, “woman is always,via Derrida, that which calls out to Man, that which puts him into question.”[↩]

- See Meltem Ö Gürel and Kathryn H. Anthony, “The Canon and the Void: Gender, Race, and Architectural History Texts”, Journal of Architectural Education, 59/3 (2006): 66- 76, Sibel Bozdogan, “Architectural History in Professional Education: Reflections on Postcolonial Challenges to the Modern Survey,” Journal of Architectural Education, 52/4 (1999): 207-215, Karen Kingsley, “Gender Issues in Teaching Architectural History”, Journal of Architectural Education, 41/2 (1988): 21-25 and a special issue of Art Journal, 54 (Fall 1995) devoted to the art history survey text and survey course that includes pertinent material.[↩]

- See Sykes, “Introduction” in Sykes (ed.), Constructing A New Agenda, pp.14–29.[↩]

- Arguably the first architectural theory anthology was Ulrich Conrads’ Programs and Manifestoes on twentieth-century architecture published in 1964, but the emergence of the theory anthology as a stable, recognizable genre should be dated to the mid 1990s. The anthologies consulted for this essay are: Jay M. Stein and Kent F.Specklemeyer, Classic Readings in Architecture (Boston: McGraw Hill,1999), Kate Nesbitt, Theorizing a New Agenda for Architecture: An Anthology of Architectural Theory 1965-1995 (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996), Neil Leach (ed.), Rethinking Architecture: a reader in cultural theory (Routledge: London and New York, 1997), K. Michael Hays (ed.), Architecture Theory Since 1968 (London, England/ Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1998), Harry Francis Mallgrave and Christina Contandriopoulos (ed.), Architectural Theory: Volume II An Anthology from1871 to 2005 (Blackwell 2006), Charles Jencks and Karl Kropf (ed.), Theories and Manifestoes of Contemporary Architecture (Chichester: Wiley Academy, 2006), A. Krista Sykes (ed.), Constructing A New Agenda: Architectural Theory 1993–2009 (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2010). This paper does not review Joan Ockman with Ed Eigen’s Architecture Culture 1943-1968: A Documentary Anthology (New York: Rizzoli, 1999) since their theory anthology ends before the emergence of feminist architectural theory. On canonization see Miriam Gusevich, “The Architecture of Criticism: A Question of Autonomy”, in Andrea Kahn (ed.), Drawing Building Text (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1991),p. 8. “The architectural canon is an effect of criticism,” notes Gusevich.[↩]

- Sylvia Lavin also interprets this collections as historical constructions in her review of the anthologies edited by Joan Ockman, Neil Leach and K. Michael Hays respectively. See Sylvia Lavin, “Theory into History: Or, the Will to Anthology”, The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol.58, no.3 (September 1999): 494-499. For critiques of the survey method see footnote 2 above.[↩]

- Elizabeth Grosz, “Conclusion: A note on essentialism and difference,” in Sneja Gunew (ed.), Feminist Knowledge: Critique and Construct (London and New York: Routledge, 1990), p.334.[↩]

- Thus Stein and Spreckelmeyer include an essay from Dolores Hayden on the inscription of the public history of “women and ethnic minorities” in Los Angeles and Claire Cooper Marcus discusses the meaning of home including its value for pregnant women. Neither of the essays is collected under the heading of feminist discourse, women’s history, work on sexual difference etc. The Mallgrave and Sykes compendia have no essays distinguishable as feminist by allocation or internal content although arguably the Sylvia Lavin essay in Sykes collection which deals partly with the phallic form of recent icon buildings could be reinterpreted as a gendered reading.[↩]

- By several of the anthology accounts, feminism’s temporal relation to the collected material is untimely. Thus Michael Hays acknowledges the emergence of feminism and other politics of subject formation but claims they emerged after 1993 when his anthology finishes. Nesbitt observes that feminism is one of the three emergent trends of the 1990s and so given her anthology finds completion in 1995 it’s perhaps implied that this emergent trend is relatively little surveyed. In both these projects feminism lies in the future. It’s difficult to see then what happened to that future.[↩]

- Readers can easily consult the 8.5 pages, 1970s-2000 bibliography on gender, space and architecture included in Jane Rendell, Barbara Penner and Iain Borden (eds.), Gender Space Architecture: An Interdisciplinary Introduction (London and New York: Routledge, 2000), pp.414–423.[↩]

- I am paraphrasing a sentence from Stephen Greenblatt and Catherine Gallagher’s essay, “Counterhistory and the anecdote,” in Stephen Greenblatt and Catherine Gallagher (eds.), Practicing New Historicism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), p.59.[↩]

- Moreover, other kinds of axes of difference in subject formation – class, race, ethnicity, sexuality – are almost non-existent in these collections.[↩]

- See Meaghan Morris and Anne Freadman, “Import Rhetoric: ‘Semiotics in/and Australia”, in Peter Botsamn, Chris Burns and Peter Hutchings (eds.), The Foreign Bodies Papers (Sydney: Local Consumption Publications, 1981), p. 152.[↩]

- Agrest dates the essay’s writing from 1971 to 1978 and its publication in 1988 in the contents’ index of her collected essays. See Diana I. Agrest, Architecture From Without: Theoretical Framings For A Critical Practice (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1991), p.v.[↩]

- Agrest, “Architecture From Without”, in Architecture From Without, p.174.[↩]

- Agrest, “Architecture From Without”, in Architecture From Without, p.173.[↩]

- Nesbitt, Theorizing A New Agenda, p. 541.[↩][↩]

- Agrest, “Architecture From Without”, in Architecture From Without, p. 3.[↩]

- Mark Wigley, “Untitled: The Housing of Gender” in Beatriz Colomina (ed.), Sexuality & Space (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1992), pp.327–389.[↩]

- See Mirjana Lozanovska, “Uomo Universale: The Imaginary Relation Between Body and Mathematic(s) in Architecture”, Architectural Theory Review, vol.14, no.3 (October 2009), p. 243.[↩]

- Thus Tschumi and Eisenman both appear in the body section and in the “Post structuralism and Deconstruction” category and Eisenman appears in the “Historicism” category and the “Definitions of the Sublime” categories.[↩]

- The essay was originally published in Assemblage 17 (April 1992): 6–29. I have distinguished between Neil Leach’s use of Cixous in a work on cultural/philosophical theory and the architectural focus of the Agrest and Bloomer essays included in Nesbitt and Hays’ anthologies.[↩]

- Hays (ed.), Architecture Theory Since 1968, p. 758.[↩]

- Jennifer Bloomer, “Abodes of Theory and Flesh: Tabbles of Bower”, Assemblage, 17 (April 1992), p. 7.[↩]

- Bloomer, “Abodes of Theory and Flesh”, Assemblage, 17 (April 1992), pp. 9, 7.[↩]

- Bloomer, “Abodes of Theory and Flesh: Tabbles of Bower”, Assemblage, 17, p.7[↩]

- Hays, Architecture Theory, p.758.[↩]

- I have discussed this in my essay “Ex libris: archaeologies of feminism, architecture and deconstruction”, Architectural Theory Review, 15/3 (2010) : 242–265.[↩]

- Jennifer Bloomer, Architecture and the Text: (S)crypts of Joyce and Piranesi (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1993), p.54, p.152 respectively.[↩]

- Hays, Architecture Theory, p.759.[↩]

- Jennifer Bloomer (ed.), “Architecture and the Feminine: Mop-Up Work”, Any, 4 (January/February 1994), p.8.[↩]

- Bloomer, “Architecture and the Feminine”, p.11.[↩]

- Cynthia Davidson, “Dear Jennifer”, in Bloomer (ed.),“Architecture and the Feminine”, p. 7.[↩]

- Hélène Cixous, “The Laugh of the Medusa”, in Elaine Marks and Isabelle de Courtivron (ed.), New French Feminisms: An Anthology, (Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1980), p.245;p . 243. Margaret Whitford notes that the label has been “attached by others to Luce Irigrary’s work”. See Margaret Whiford, Luce Irigrary: Philosophy in the Feminine (London and New York: Routledge, 1991), p.38. Alice Jardine discusses Cixous’s reading of Derrida and use of this term. See Jardine, Gynesis, pp.261-262. There is a brief discussion of “the misleading term” écriture féminine and its Anglophone usage in Elizabeth Guild, “écriture féminine” in Elizabeth Wright (ed.), Feminism and Psychoanalysis: A Critical Dictionary (Oxford: Blackwell, 1993), p. 74.[↩]

- Leach, Rethinking Architecture, p.302. Leach observes, “Cixous has argued for a sexual difference based on openness to the other, and has promoted a ‘feminine writing’ – écriture feminine (sic) – as a strategy of exploring difference in a non-exclusionary mode. Such writing is not limited to women, however, and some of the best examples have been the works of male authors such as James Joyce.” Hays frames it this way, “For Bloomer, intimations of an architecture féminine can be found in male authors like James Joyce, Walter Benjamin, and Jaccques Derrida, who also seek to undermine phallocentric discourse.” See Hays, Architecture Theory, p. 759.[↩]

- For an analysis of Cixous’s unravelling of the feminine element in Jacques Derrida’s texts see Jardine, Gynesis, pp.261–262.[↩]

- Jardine, Gynesis, p.262. [↩]

- Leach, Rethinking Architecture, p. 318.[↩]

- Sarah Harasym (ed.), Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, The Post-Colonial Critic: Interviews, Strategies, Dialogues (New York and London: Routledge, 1990), p. 102.[↩]

- Spivak, The Post-Colonial Critic. p. 102.[↩]

- This collaboration and their use of “chora” has generated substantial feminist critique. See Sue Best, “Sexualizing Space” in Elspeth Probyn (ed.), Sexy Bodies (1995), pp.181-194; Anne Bergren, “Architecture Gender Philosophy” in John Whiteman, Jeffrey Kipnis and Richard Burdett (eds.), Strategies in Architectural Thinking (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1992), pp. 8–47 and Elizabeth Grosz, “Women, Chora, Dwelling”, in Bloomer (ed.), “Architecture and the Feminine”, pp. 22–27.[↩]

- Grosz, “Women, Chora, Dwelling”, in Bloomer (ed.), “Architecture and the Feminine”, p. 27.[↩]

- Editorial Collective, Editorial, Questions feministes, 1 (1977), trans. Yvonne Rochette-Ozzello in Marks and de Courtivron (eds.), New French Feminisms, pp. 2, 243.[↩]

- See Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard, “Introduction: Feminism and Art in the Twentieth Century”, in Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard (eds.), The Power of Feminist Art (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1999), pp. 20–29 for a sympathetic discussion of the biological and sexual emphasis of 1970s feminist art and the objections mounted to it.[↩]

- See Lawrence Grossberg, Cary Nelson and Paula Treichler (eds.), Cultural Studies (New York/London: Routledge, 1992).[↩]

- For readers seeking to supplement the anthological representation of feminist and gender studies theory I recommend the following texts. For the 1970s and early 1980s see Women in American Architecture (1977), Heresies, issue 11 (1981) “Women and Architecture” and the book Women and the American City (1980), as well as Matrix’s, Making Space: Women and the Man-Made Environment (1984). The late 1980s and 1990s are well represented in the collections Sexuality & Space (1992), The Sex of Architecture (1996), Architecture and Feminism (1997), Desiring Practices (1997), Stud: Architectures of Masculinity (1996), The Architect: Reconstructing Her Practice (1996), Drawing on Diversity: Women, Architecture and Practice (1997), Discrimination by Design (1994) and by essays in Strategies in Architectural Thinking (1992) and Drawing/Building/Text (1991). The shift into the later 1990s and new millennium is partly signaled in the Desiring Practices’ collection (1997) and the Any issue “Architecture and the Feminine”, 4 January/February 1994, but fully apparent in Altering Practices (2007), Material Matters (2007), Peg Rawes’ Irigaray for Architects (2007) and some of the essays in Architecture and Participation (2005) and the writing issue of Architectural Theory Review, 15/3, December 2010. Jane Rendell, Barbara Penner and Iain Borden’s anthology Gender Space Architecture (2000) includes extracts from some of this late twentieth-century material, contextualized within a larger field of non-architectural feminist work by writers, philosophers and theorists. This anthology includes a large bibliography. Please note the suggestions offered above produce an anglophone theory list. These suggestions do not include the large body of work produced by architectural feminist and gender studies historians nor work undertaken in India, Europe or even Australia.[↩]