Delayed parenthood, infertility and the use of assisted reproductive treatments are increasingly common in Australia, yet they often exist in the shadows, little discussed and understood. Yvonne Meng investigates the impacts of work and career on family planning and generously shares her personal fertility journey.

So, when are you having kids?

I hesitated before answering.

I have dogs, I say.

But don’t you want kids?

I’ve been in conversations like this more often than I’d like. I am a 39-year-old professional woman and I am childless, but it’s not for the lack of trying. For three years, my husband and I tried fruitlessly to conceive. We tracked cycles, took pills, and I was poked and prodded while undergoing a myriad of testing, only to be told we have ‘unexplained infertility’. Our recent foray into IVF resulted in one lonely embryo and a heartbreaking miscarriage, made all the more devastating because my ‘advanced’ age meant that my chances of conceiving – whether naturally or through assisted reproductive treatment – was diminishing with every passing month.

In Australia, it is estimated that one in six couples are affected by infertility.1 The World Health Organization defines infertility as a “disease of the male or female reproductive system defined by the failure to achieve a pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected sexual intercourse”.2 For women over 35, doctors recommend seeking assistance after six months of trying to conceive, because female eggs are known to drastically decrease in number and quality after that age. Male fertility declines too, with men over 40 more prone to issues such as poor sperm quality and DNA damage, which in turn can affect conception and carry a higher risk of abnormal pregnancies.

Despite the biological roadblocks, people are delaying starting families. The current median age for motherhood is 31.7, and 33.7 for men, numbers which have been steadily increasing for the past 50 years. For new mothers, 51% are now aged over 30 compared to 15% in 1981. The proportion aged over 35 – those so-called ‘geriatric mothers’ – is also growing. Some studies suggest that women put off motherhood to pursue education or career goals. Others attribute barriers to parenthood to the high cost of housing, donor availability, or simply not finding a suitable partner in time. Whatever the individual motivations, assisted reproductive treatments are on the rise and in 2021–2022, 16,971 patients were treated for infertility in Victoria alone – up 8% from the previous year.3 Yet, even with the prevalence of IVF in the community, navigating infertility and career is not very visible, despite the emotional, physical and financial impact it can have. In addition, fertility is not well understood by younger women and men. In a study with Australian university students, a group more likely to delay parenthood, many underestimated the impact of age on fertility and overestimated what they could achieve financially and professionally before they conceived.4 I was very unprepared for my own fertility journey. My younger self believed I could choose when I would have a baby and that if I decided to do it, it would simply happen. I didn’t realise that it could be so hard.

The choice to delay motherhood

In my 20s, my priorities were to survive architecture school and hopefully land a job at the end. Architecture is a long and demanding course and I started late. When the first school friends began getting married, I was in the uni computer labs at 3am pushing out last minute renders. When the babies started arriving, I was pulling the hours in my $38K-a-year graduate job, single and renting in a share house. I travelled whenever I could and kissed some toads; kids were the last thing on my mind.

Frankly, having a child was a scary prospect. I had read so much about women in the profession disappearing after becoming mothers, or having their responsibilities docked after taking time off for maternity leave. Child-bearing years coincide with career-advancement years, and I dreaded the ‘motherhood penalty’ where a woman’s earning potential tanked after having children. 5 I didn’t want any of that. I wanted financial security, a loving partner, and established career before even considering progeny. Besides, I naively thought. There’s always IVF.

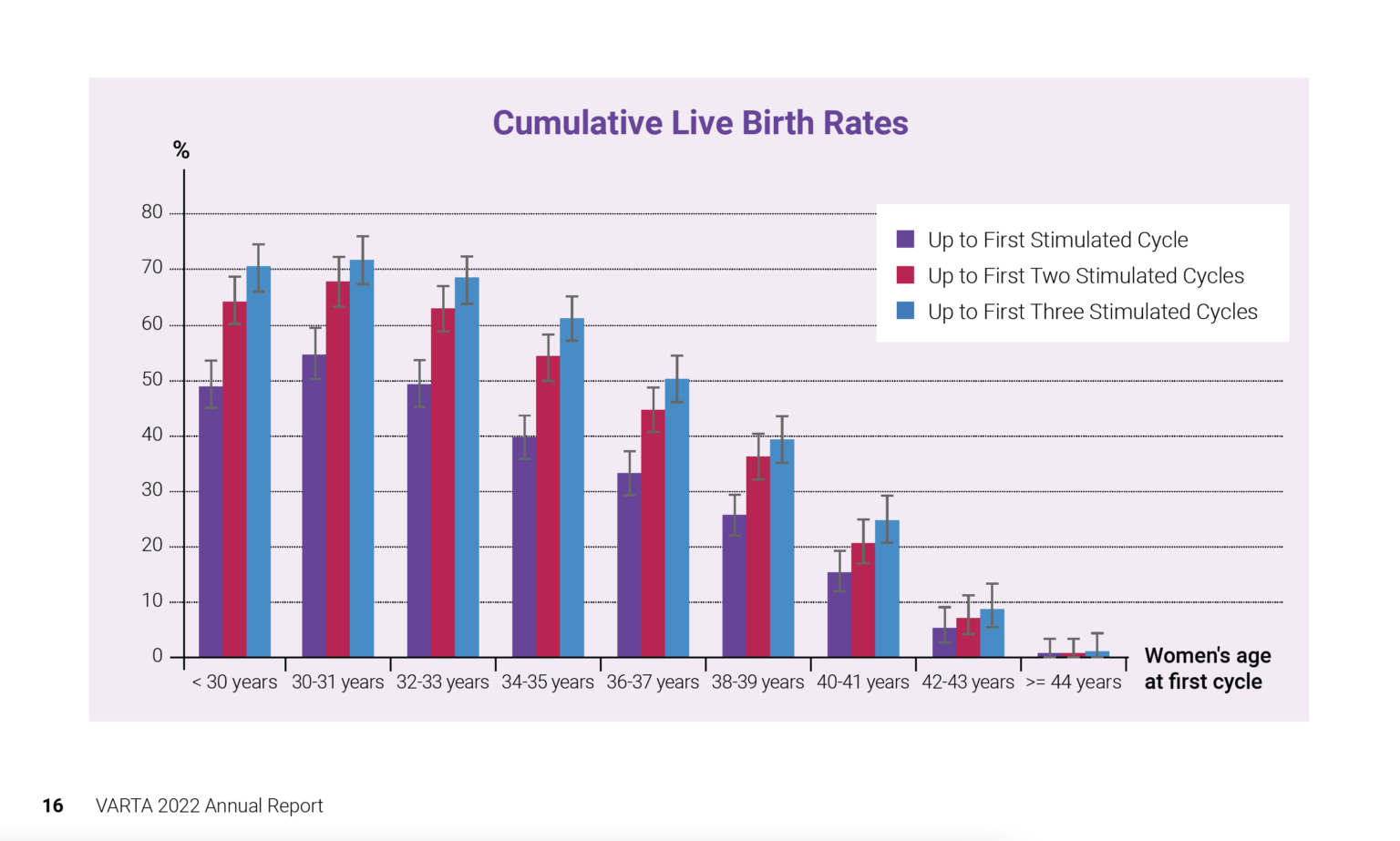

But IVF is no magic bullet. In fact, despite what the glossy marketing material may suggest, the success rate is not very high. Live births make up only 30% of treatments, and like natural conception, this declines with age. The age you begin IVF is the greatest indicator of whether the treatment will bear fruit. A woman under 30 has a 49% chance of bringing home a baby after one stimulated cycle, and 71% after three. At 40, this becomes 15% and 25% respectively.3 Prior to being deemed infertile, I had no idea the odds were so low.

In my early 30s, I met my now-husband and I started the financially precarious process of being my own boss. By my mid-30s, I had chosen to pursue a PhD (it’s still unfinished, by the way) and as the biological clock ticked past the 35-year milestone, I started to think more about starting that family. In no way did I feel ready, and I didn’t know how a child was going to fit into my life or my tiny apartment. I only had a vague notion that there would be one somewhere in the future, and that she would be a girl.

At 38, after years of monthly disappointments we finally turned to a specialist who told us that if we wanted a biological child our best chances were through IVF – and we needed to get cracking. So, at the end of July 2022, I found myself sitting on the edge of our bed nervously as my husband administered the first of many hormone-filled syringes (I couldn’t bear to do it myself) so that I could undergo a procedure which harvested my eggs to then fertilise in a petri dish.

I got pregnant on this first cycle, but sadly it lasted only eight weeks. In the weeks following my miscarriage, I cried a lot and bought several pairs of shoes. I was angry. I was angry at being fed the belief that “you can have it all”. I was angry at the high cost of housing and Sheryl Sandberg for telling us to “lean in”. And I was angry at architecture for taking so damn long that I had unknowingly hijacked my chance at a family. Amidst my hormone-fuelled self-pity, I mostly lamented that I had delayed trying. There is no way of knowing whether I would have been successful had I started at a younger age, but at least I would have had more time on my side. I tried to get my ducks lined up neatly in a row, but biology didn’t agree with that strategy.

The IVF experience

IVF is an invasive and gruelling process and the physical side effects were rough. At one point, I got Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome (OHSS) where my ovaries blew up into waterlogged tennis balls and released fluids into my surrounding organs, making it painful to move and sometimes breathe. But it was the emotional strain that was the worst. I felt during those months that my life was put on hold. We were in a constant state of waiting. How many eggs would we get? Did any of them fertilise? Am I pregnant yet?

Clinics often suggest that the ‘optimal’ number of stimulated cycles is three, although it is not uncommon to endure even more rounds of this torture in the hope of having a baby. Many clinics are privately operated and require large upfront costs of $9–12K per cycle, not including hospital fees or medication. Even with Medicare rebates, multiple rounds can quickly amount to the tens of thousands. There are a small number of low-cost bulk bill clinics; however they may not offer more advanced treatments and have limits on age and BMI. In October 2022, the Victorian government launched a public fertility program offering free IVF to up to 4000 people a year. While this is a great initiative, especially for those who could not previously access treatment due to expense, the wait times are expected to be long. This may not be an option for women starting in their late 30s and early 40s.

The process itself is time consuming and involves numerous blood tests, appointments and phone consults. In addition, there is the time required for physical recovery from egg retrievals, and emotional recovery from failed cycles. Fertility clinics, like most businesses, operate between 8am and 6pm. For people undergoing multiple rounds, this is months, sometimes years of navigating highly personal appointments during working hours.

Throughout my cycle, my business partner was supportive and compassionate, and I never felt the pressure to stay at work when my mind and body were not up for it. However, under the national Fair Work Act 2009, taking time off for IVF treatment is not a legitimate use of personal leave “as women undergoing treatment are neither ‘ill’ nor ‘injured’”.6 It is up to individual organisations to offer specific fertility leave.7 In addition, if a person does not have a compassionate workplace or does not feel comfortable to disclose such a sensitive experience, it can make an already stressful situation worse.

I have only been through one cycle, but with the low chances of success I don’t know if I have it in me do it again. I will be 40 this year. Yet I haven’t ruled it out completely because of that tiny window of hope that IVF offers, but unfortunately can’t promise.

I am currently going through the process of reordering how I see my future, given that I may very well remain childfree. A quarter of Australian women will never have children. Being a woman does not equate ‘mother’, and there are many factors – sometimes by choice, sometimes by circumstance – that mean a woman remains childfree. However, common rhetoric suggests that if you are not a mother by a certain age, you must be either a cold-hearted career woman or a lonely spinster. I am neither. I may have simply missed the boat. If my fertility journey doesn’t work out, I will ultimately have to be ok with that.

Infertility exists in the shadows and is not well discussed. It is personal, and often quite painful. However, I strongly believe it needs to be better understood so that younger people can make educated decisions about planning families if they want one, and that those undergoing treatment can be well supported in the workplace. Being a working parent in Australia is hard, and there need to be suitable options so that the choice to start a family doesn’t feel like a threat to your career. The Labor government’s plans to increase parental leave and childcare is a good start, but workplaces also require significant cultural shifts. We need proper fertility education and discourse because infertility is more common than you think. For my personal situation, I wish I was better informed at an earlier age. Perhaps my life choices might not have changed, but I would have at least been more prepared.

Infertility can be a very isolating experience. I was lucky that I had good emotional support, in particular from a friend who has been on the journey a little longer than I have. The daily check-ins got me through – finally someone else who understood the joys of progesterone pessaries and how to respond when things got a bit too much. You know who you are. Thank you. — Yvonne Meng

Image by Nadezhda Moryak, from Pexels

- Tanmay Bagade, Kailash Thapaliya, Erica Breuer, Rashmi Kamath, Zhuoyang Li, Elizabeth Sullivan & Tazeen Majeed (2022). Investigating the association between infertility and psychological distress using Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (ALSWH). Scientific Reports, 12(1), 10808–10808. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-15064-2 [↩]

- World Health Organization (WHO). International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11) Geneva: WHO 2018.[↩]

- Victorian Assisted Reproductive Treatment Authority, ‘Annual Report’ (2022)[↩][↩]

- Eugenie Prior, Raelia Lew, Karin Hammarberg & Louise Johnson (2019). Fertility facts, figures and future plans: an online survey of university students. Human Fertility (Cambridge, England), 22(4), 283–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/14647273.2018.1482569.[↩]

- The October 2022–23 Budget, a Treasury report, found that women’s earnings were reduced by 55% in the first five years of parenthood. , accessed 16 November 2022.[↩]

- Thomas Hvala (2018). In vital need of reform: “Providing certainty for working women undergoing IVF treatment”, University of New South Wales Law Journal, 41(3), 901–938. https://doi.org/10.53637/UQZR3499.[↩]

- Westpac and the NSW government are two organisations who offer fertility leave provisions for their employees: https://www.westpac.com.au/news/in-depth/2022/11/fertility-leave-the-new-family-friendly-frontier/, accessed 17 January 2023; https://arp.nsw.gov.au/m2022-09-paid-leave-in-the-event-of-a-miscarriage-pre-term-birth-or-when-undergoing-fertility-treatment/, accessed 17 January 2023.[↩]