“It is hands-down the best history of women architects I’ve ever read.” Julie Willis reviews a comprehensive new history of New Zealand women in architecture.

Aotearoa New Zealand has long been recognised as a place that advances the standing of women in society. It was, after all, the first country in the world to grant women the vote, in 1893. But, to date, there has been no comprehensive account of women in architecture in Aotearoa New Zealand aimed at a wide audience, this despite excellent individual projects. It is thus very welcome that Elizabeth Cox and her co-contributors have drawn together an extraordinary amount of new research into the very handsome volume Making Space: A History of New Zealand Women in Architecture. And what a contribution it is: it is not perfect, but it is hands-down the best history of women architects I’ve ever read.

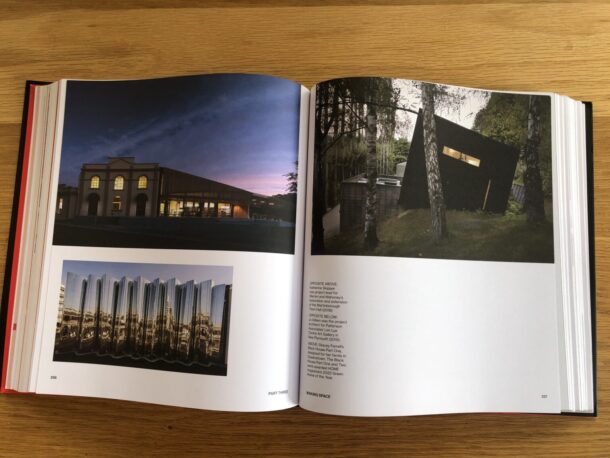

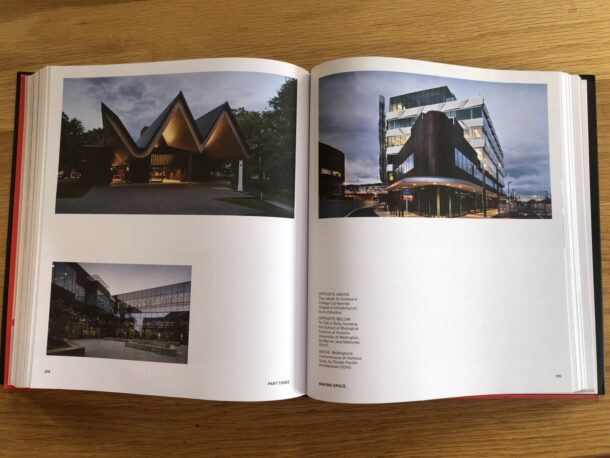

The tone is set by Cox’s thoughtful introduction, setting out the rationale for the project, the importance of recovering women’s contributions and how this leads to a more nuanced understanding of the profession and architectural production. This is followed by three main sections: the first, examining women in architecture 1840–1945; the second 1945–2000; and the third, 2000–2020. The first two sections (twelve and fifteen chapters apiece) offer a mix of biographical chapters on the careers of individuals and topic-based chapters that explore the work of groups of women who’ve made important architectural contributions. The third section takes a thematic approach, accommodating the comparatively large volume of women working in architectural practice in the first decades of the twenty-first century. The twenty-one chapters in this section focus on different cohorts to sketch out the breadth of the contribution women are making to all aspects of the built environment in contemporary Aotearoa New Zealand, including: Māori architects, Pasifika architects, activist architects, landscape architects, women in heritage, women designing cooperative housing, women involved in big civic projects, and the experiences of students of architecture. Importantly, the chapters focused on Māori women are not just in the third section but found across the volume.

Readers outside Aotearoa New Zealand will notice the reflexive inclusion of Māori language in the book. This reflects the rapid rise in recent decades of the ability of Māori and Pakeha (non-Māori) alike to speak te reo (the language) in Aotearoa New Zealand. This is impressive. But for those of us with no or limited Māori (I can recognise maybe thirty words), the book at times will be a challenge to read, particularly as there are no translations offered nor a glossary to assist non-speakers. Some may struggle to distinguish between the names of iwi (tribes) and place names, and it is distinctly helpful if you already know what wāhine and whakapapa mean (women and lineage). This book presumes an Aotearoa New Zealand audience, but it should be read and appreciated much more widely, so Māori translations to engage and inform a larger audience would have been helpful.

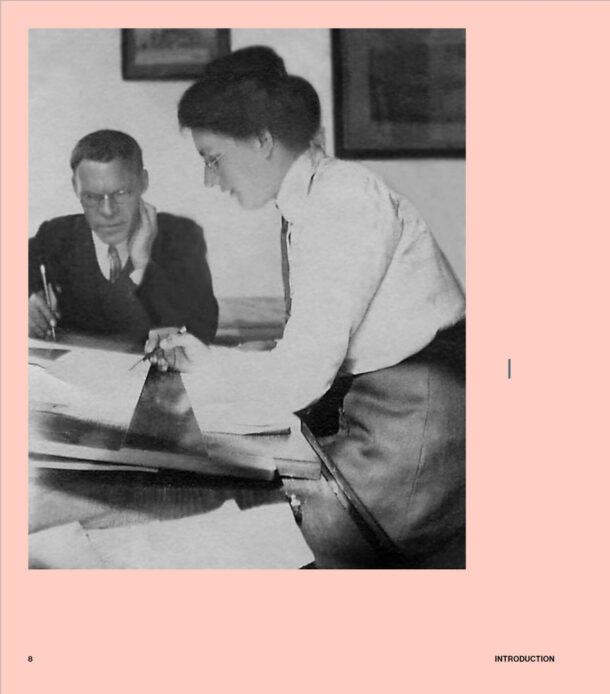

The book documents the usual assumptions about the need (or not) for women architects voiced by commentators across the late nineteenth and first half of the twentieth century: as reported in a 1917 newspaper article, women architects were desirable because they would bring “intellect” to house design and the inclusion of labour-saving devices (p. 56). Even the head of the architecture school at Auckland University, Cyril Knight, saw no barrier to women entering the profession, observing in 1926 that their value would be in designing and decorating houses (p. 48). And in 1945, Dunedin architect Basil Hooper saw “no reason” why women couldn’t be successful architects, pondering why those who had qualified to date were not more prominent. He went on to question whether women would have sufficient “business capacity” to run a practice or sufficient site experience, given it wasn’t nice for women to be “climbing ladders and walking along frail scaffolds” (p. 120). Such were the arguments made all over the world during these times: attributes and capacities projected on to women, consciously or unconsciously, with a view to limiting their contributions to architecture to a narrow band of practice that is socially acceptable.

This history of women in architecture in Aotearoa New Zealand simultaneously demonstrates the evolving nature of the profession and architectural production from 1845, offering nuance and depth beyond the standard histories of NZ architecture (such as that of Peter Shaw), and the prevailing social mores and expectations that women were subjected to in those times. It was by no means an uncommon experience for unmarried pregnant NZ women to “cross the ditch” to the relative anonymity of Australia to give birth and place the child up for adoption, but it is profoundly confronting to understand that one of NZ’s earliest women architects did exactly that, returning to her professional life in Wellington soon afterwards. But there is also evidence of the subversion of social expectations: cousins Mary and Ellen Taylor designed a building in Wellington in 1845, combining both their business premises and home, containing just one bedroom, described by Mary to her friend Charlotte Brönte as “our bedroom” (p. 24). And Muriel Lamb, whose family circumstances disrupted her aim to become an architect on completion of her secondary schooling, returned to the idea after her marriage, enrolling in a diploma of architecture course at the Auckland University College in 1943, at the age of 31. Her maturity and more experienced world view put her at odds, at times, with her lecturers, and she was determined not to “pander to the men” (p. 164). She went on to a successful career, balanced with the demands of two adopted children. Other women at the time also managed to combine marriage, motherhood and practice. For example, Monica Barham, as one half of a husband-and-wife firm, bore six children between 1946 and 1953 and continued her architectural work by setting up her drawing board in the living room corner.

Overall, the writing standard of the contributions is very high, and the book presents an extraordinary depth of research that recovers the contributions of many hither-to unappreciated women designers and makers of the built environment. Elizabeth Cox’s editorship and own writing contributions must be especially noted; it is clear that without her vision, the book would not be such a tour de force.

Making Space amply demonstrates that women architects in Aotearoa New Zealand contributed to all aspects of architectural production. At times, they fought against the odds, inherent assumptions and outright prejudice to qualify and practice in the profession, but overwhelmingly they just got on with it, seemingly unwilling to be cowed by any barriers in their way. And here this book is particularly refreshing. It presents the histories of women in architecture in a straightforward, no-nonsense manner. It is not overly theorised, and the prejudice and difficulties faced by these women not over-catastrophised. At no point are the contributions of the women overstated or eulogised beyond credibility.

Collectively, the contributions of these women to Aotearoa New Zealand’s built environment are hugely significant and this is an extraordinarily important documentation that will inspire all who read it.

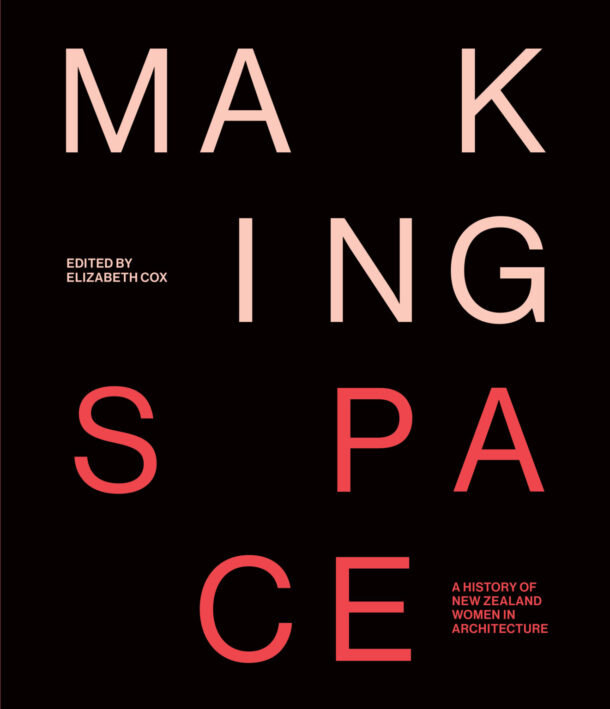

Elizabeth Cox, ed. Making Space: A History of New Zealand Women in Architecture (Auckland: Massey University Press, 2022).

Julie Willis is a co-founder and director of Parlour. Professor of Architecture and Dean of the Faculty of Architecture, Building & Planning at the University of Melbourne, she is an authority on the history of Australian architecture 1890-1950. Among many other publications, Julie is co-author of the book Women architects in Australia 1900-1950, with Bronwyn Hanna (Australian Institute of Architects, 2001) and co-editor of the Encyclopedia of Australian Architecture (Cambridge University Press, 2012).