How do you make a successful and effective organisation? Wendy Bertrand reflects on forty years of the Organization of Women Architects and Design Professionals.

It was during a peak in the American women’s movement of the 1970s that I began attending the College of Environmental Design at the University of California in Berkeley, California. Attention to women’s issues seemed essential to social progress (and to my personal progress), so combining what I was learning about feminism with my love of architecture felt right. It made sense to join with other women in architecture to create a new organisation; one that would directly address the many challenges facing us as women in a male-dominated profession – and through the free exchange of information, ideas, and activities – to strengthen our professional success.

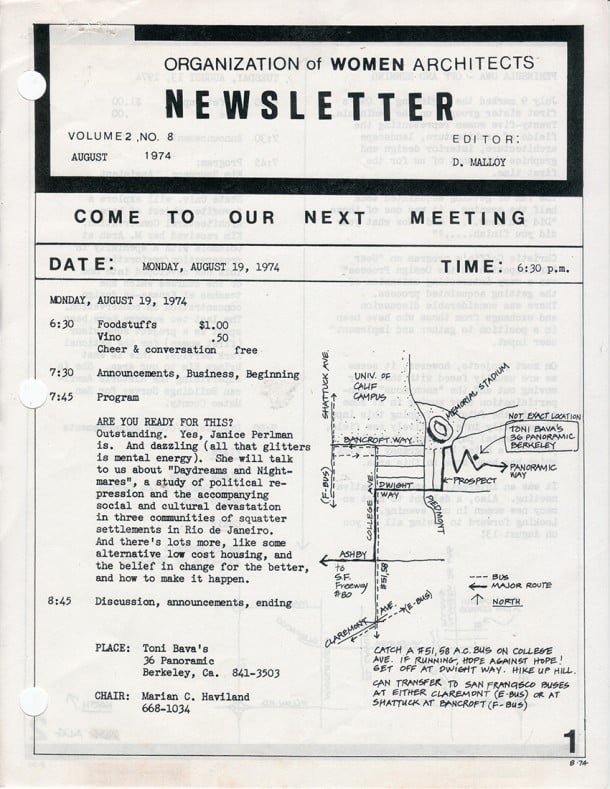

We founded the Organization of Women Architects and Design Professionals (OWA), which is now celebrating its fortieth year. I was one of the founding members interested in the organisational elements – I even diagrammed a structural proposal for our November 1972 meeting that we used in designing our organisation. I have remained a champion of transparency of steering committee actions and the periodic review of our mission. This worked – my notes from the March 1986 steering committee meeting, which I attended, show discussions about goals and process.

Not all members are comfortable with various aspects of the reviewing process, such as: analysing pivotal turns, recognising missed opportunities, and understanding the potential consequences of past organisational structure, policy and cultural behavior. I don’t, however, see analysis and review as airing dirty laundry. Just the opposite – I see them as the necessary brooms and polishing rags for cleaning up organisational instability, awkwardness and confusion, and for ensuring organisational purpose and satisfaction. Sincere dialogue can produce enriching results. It is in this spirit that I offer the following commentary about OWA, from the inside. I write here as an individual OWA member, not as a current OWA Steering Committee member. My concerns are with patterns and satisfaction. I want to bring to the surface some of our successes, strategies and struggles for others to consider as they form groups.

Successes

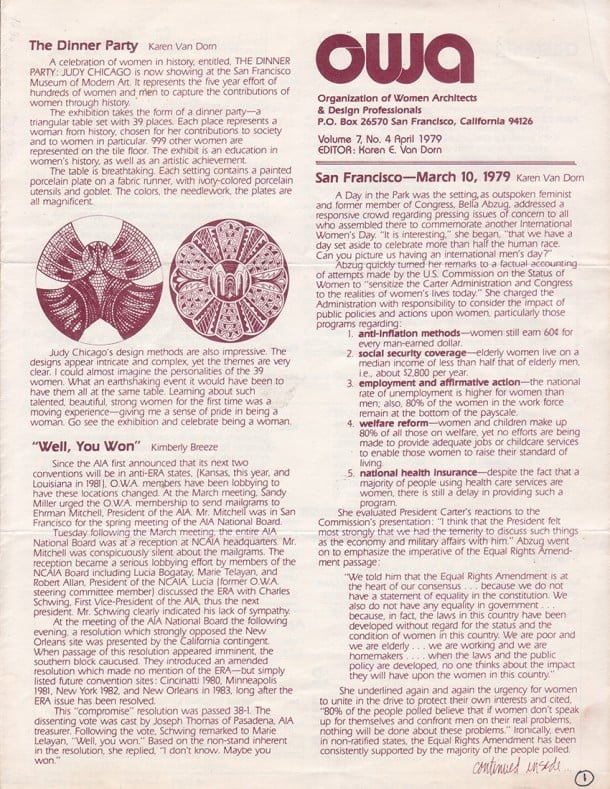

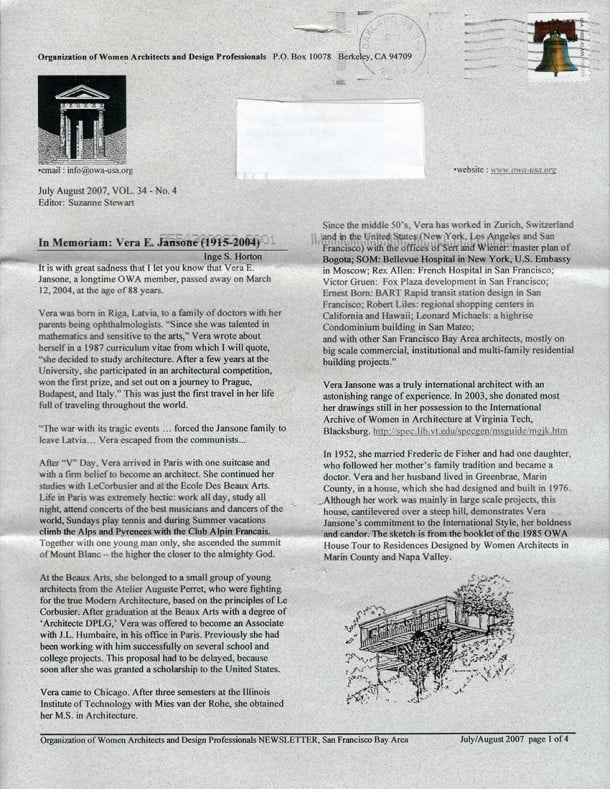

OWA was founded in 1973 in the San Francisco Bay Area. I think many of us feel that when you give birth to an organisation, and work hard to raise it (during the first twenty years), you develop something like the unconditional love of a parent. Although members have come and gone, and many architects don’t know of our existence (we do not market ourselves), I am proud of the enduring presence, the low membership dues, the improvement of record keeping, the dedication of many steering committees, excellent website, and the organisation’s broad range of members. OWA is an admirable entity with a positive and worthy image as a professional organisation of mostly women, willing to remind others that women are active and valuable participants in the environmental design professions.

From my long perspective, I would like to highlight several reasons for our longevity.

Timing and newness

The climate of fairness fueled by the women’s movement and the affirmative action laws, provided ideal conditions for creating something new, and that newness, plus personal ambitions, pulled us together. The timing was good as the American Institute of Architects (AIA) held its 1973 National Convention in San Francisco and we moved quickly to become visible and to promote the OWA as part of the profession. Some of our members were both AIA and OWA members and knew what was not happening for women in AIA, so we agreed to form as an independent group.

Commitment and bonding

Our hard work for the organisation bonded us – working together often tends to make professional friends. These friendships became unusually strong because we were growing up together in architecture (and a few other design professions), we liked each other, and there was a common positive social climate within feminism to be supportive. We were giving birth to change.

Need

There was an obvious need for the OWA because prominent male architects were publicly saying that they would not hire a woman architect; something which highlighted the fact that discrimination was not an individual problem. This was a class problem – the class being women, the problem being sexism.

Mobilised talent

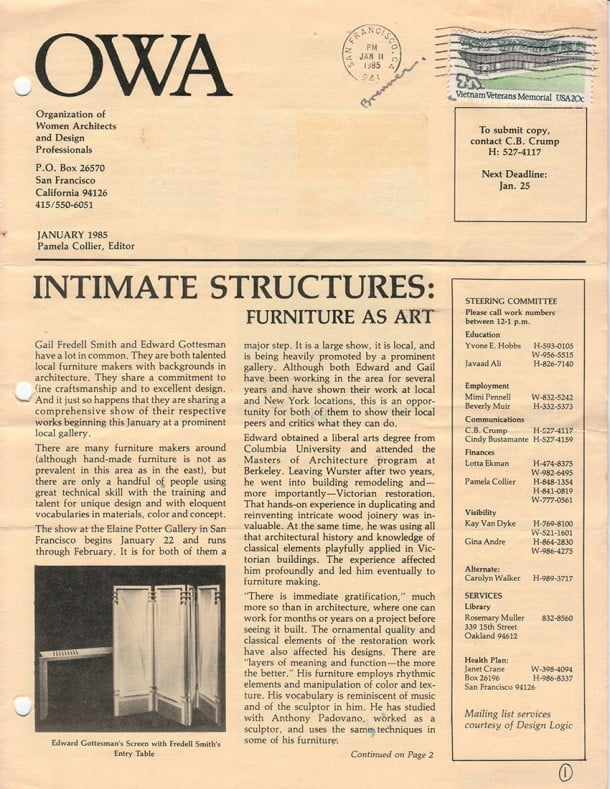

Those who joined to create the organisation were sharp, talented and energised to participate beyond the minimum expectations of attendance, speaking up or taking on steering committee tasks. For example, members conducted a major employment survey (1974–5), lead house tours, took international trips together, represented our concerns on professional boards, listed members with their own firms in a directory, set up workshops, snapped annual group photos, formed a mothers’ subgroup, exhibited members’ work, established an annual retreat, and more.

Strategies

We, the founding members, created strategies for organisational behavior and structure that generated an umbrella effect. This enabled strong collegial participation and was something that many used for their personal interests, but which also benefitted the group. We set up OWA as a horizontal membership organisation without levels of hierarchical authority. We were aware of other groups like the Women Architects, Landscape Architects and Planners (WALAP) in Boston. Business was administered directly by everyone present at the monthly meetings in members’ homes or offices. Twelve steering committee members were elected and responsible for tasks done in between meetings; administrative chores and leadership jobs were rotated among steering committee members. The mission statement was broad and included respect for the whole person, not just the professional. After the first fifteen years of OWA newsletters, I counted one hundred editors. A steering committee ranging between seven and twelve members over forty years resulted in about 300 members serving on the steering committee, with an average annual membership of about 150 members. Early policy was for every member to find time to be a steering committee member, and we did, with some members serving two or three terms (there were no term limits – an oversight in my opinion). This level of dedicated participation is another reason why many members hold a special place in their hearts for OWA.

Struggles

We have survived our major struggles, which centred on organisational issues and purpose —both were difficult and painful to tackle. Author, educator, and architectural historian, Gwendolyn Wright, sheds light on the subject of internal organisational questioning. In her opening remarks to Women in Modernism she states, ‘[I]nternal powers are taken for granted and become uncontestable’ (October 25, 2007). She references the scientist’s term ‘cascade’, for the behavior whereby everyone keeps repeating shared presumptions and asking questions or challenging the flow is considered a hostile act to be discouraged. I would encourage groups to turn that around and treat dissent, questioning and trying out new ideas, as organic compost, not social toxicity.

In the early days, little actions that seemed minor, connected, snowballed, and then appeared messy and linked to individual people, making them uncomfortable to comment on. There was no organisational protocol or agreed-to means of calling attention to specific concerns raised, and people didn’t feel comfortable to bring them up because, from my point of view, there was not an understood positive atmosphere or time allowed for thorough discussion of sensitive topics. Poor performance was sometimes shrugged off as normal for a volunteer organisation and too many contributing members left feeling unappreciated. In 1986, as steering committee members tried to grapple with the enormous tasks to do, large notebook binders were built for each steering committee member to help them to learn the job.

About the same time, some members wanted to take political stands and were frustrated by OWA’s unwillingness to do so. These members invited other Californian women in architecture groups to form a new group outside of OWA called California Women in Environmental Design (CWED). In parallel, there were ongoing concerns about OWA’s leadership and structure, which came to a head in 1990 with two factions proposing alternative methods for dealing with problems – one side wanted to change the structure to have officers and paid staff, the other wanted to continue avoiding hierarchy and too many paid staff. These issues were passionately debated in a big meeting and followed by a vote to not change the structure. The solutions from this crisis and other smaller ones eventually resulted in the steering committee taking a 2009 decision to leave the horizontal and democratic structure of a membership organisation in favour of a layered, hierarchical structure of authority, and to adopt a public service legal name (as opposed to a membership organisation). All this was done so quickly that it was not clear how things were supposed to work, yet the change passed.

A more traditional corporate model was selected, but verbal direction contradicted the new by-laws, and this resulted in confusion. One reason for the new direction was to protect the OWA health plan, a major benefit for many members over many decades. Another reason was to more effectively address the accumulative administrative tasks that needed to be put in order. There are surely other reasons too, but I would still argue that our organisation could benefit from introducing a credible system to resolve conflicts politely and productively, and that we need friendly, dedicated occasions to discuss the deep organisational culture changes that naturally come after years of existence. One possibility might be to break OWA into smaller more focused and innovative structures. Today there is only one business meeting a year rather than the eleven meetings when we started in 1973 —as a consequence we have a very different organisation.

Conclusion

In the early years, I believe OWA members were ambitious, wanting to break down barriers that were keeping us from being full participants, particularly sexism within our profession. Even today, with a higher percentage of successful professional women architects, many still share the persistently annoying feeling that an organisation is needed to address unequal treatments. Some also feel a responsibility to help younger women succeed, through special programs. Organisations can provide benefits that individuals alone cannot, but they also require attention and time.

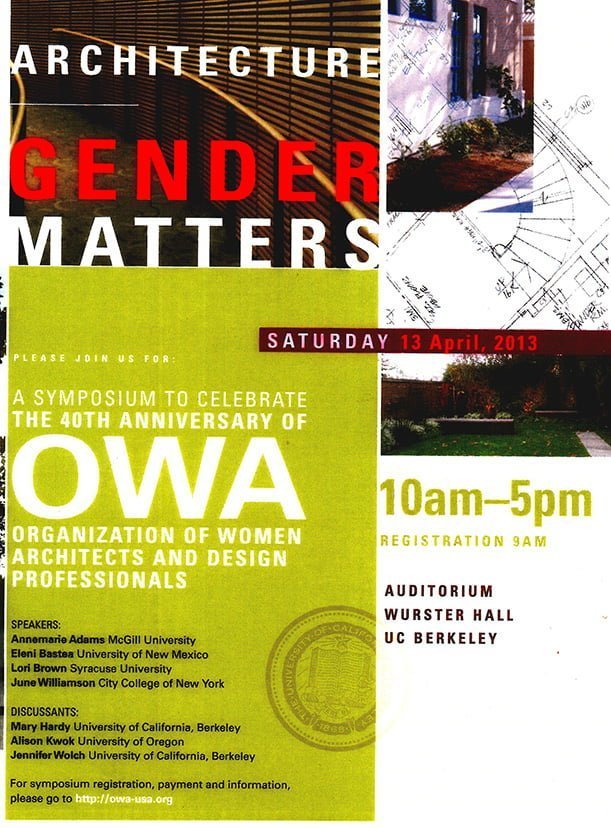

I feel that after four decades, it is now the time to update the feminist agenda. We need to add to our purpose and mission, the concern for women’s issues in our culture and focus more on understanding and acting on gender concerns in the physical and social environment. I am very interested in these social issues impacting architecture. However, it seems that a number of women in OWA that are interested in these issues, are quite shy. In my manager’s persona and knowing of the new books on feminism and architecture, I started an OWA Book Circle where eight of us have been reading and discussing books that link women and architecture. We have also devoted one circle meeting to articles about gender and architecture – many from the website archipalour.org (thank you). From time to time an innovative project comes forward – especially at decade anniversaries like the one we are celebrating this year – including the symposium Gender Matters, featuring out-of-state speakers from academia. The East Coast seems to be the center of innovative scholarship and writing, where, as expressed by one of the symposium speakers, Lori Brown (editor of Feminist Practices (Ashgate, UK 2012)), people are ‘thinking outside and beyond the practice of architecture in order to broaden and expand architecture’s role and engagement within our everyday world for everyday people’ I understand from Columbia University scholar Andrea Merrett that she and Lori Brown are part of a new feminist group of twelve architects in New York State who have formed SharE. Hearing about SharE’s contemporary feminist enthusiasm warms my heart.

My suggestion to those setting up organisations today, is to think about the organisational elements you are designing, understanding that there will need to be ways for the members of the organisation to know how to address and handle conflict openly and satisfactorily so small quirks don’t grow out of control into long-lasting hurt feelings. Use as much care for the organisation’s future maintenance and rejuvenation as for conceptual design and construction. Learn about organisational structure, policy, and behavior and make them work to meet your mission and goals. Talk about them often. Team up with sociologists interested in women’s organisations, and include a spot for a resident analyst to help regulate group behavior to insure intent and action are meaningful. And include an historian (which we have not done). Leadership comes in many forms. May I make the pitch for women and men interested in social justice values, to invent bold new shapes and colours for your successess, strategies and struggles – as individuals and as organisations.

Photographs of the OWA newsletters are by Wendy Bertrand.