Ideal proportions. Gill Matthewson discusses Architect Barbie in her paper for Fabulation, the 2012 conference of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia New Zealand. We present some out takes.

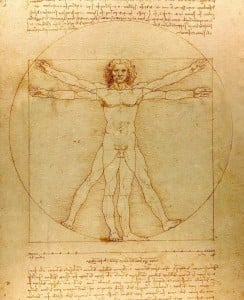

- Vitruvian Man, Leonardo da Vinci, Galleria dell’ Accademia, Venice (1485-90).

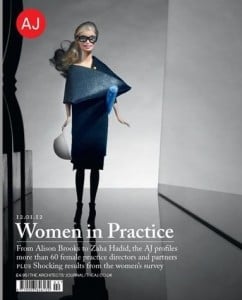

- AJ Women in Practice cover

“Haec autem ita fieri debent ut habeatur ratio firmitatis utilitatis venustatis.” – Well building hath three conditions: firmness, commodity, and delight.1

“An architect designs buildings that are strong, safe, and super stylish too!”2

Architect Barbie has provided rich fodder for discussion around women and architecture. Some of the many blog entries and internet comments ask, among other things, “how does a doll with such ridiculous proportions represent a profession that uses the human body as its base metric?”3

Architecture, following the writings of Vitruvius, bases its proportioning systems on the body, and ideas about the body underwrite architectural theory. The idea is that the symmetry and proportion evident in the human body are natural laws of beauty. Therefore in order to attain beauty in architecture, the building needs to follow the example of the body: the form of the human body should generate architectural form, its proportions define architectural proportions, and its parts supply the measures necessary for building.4

Barbie’s body has been the subject of multiple criticisms around the sexual politics of body image. Social psychologists Helga Dittmar et al tested the hypothesis of whether “Barbie makes young girls want to be thin” and concluded that Barbie must be considered “a highly significant, if not the only, vehicle through which very young girls internalize an unhealthily thin ideal.”5 If Barbie’s is considered the ideal body shape for women it is a shape that is both non-Vitruvian and physically impossible.

Vitruvius suggested that the navel is the natural centre of the human body and that a circle centred on the navel will touch the hands and feet. To encompass Barbie’s body in a circular form the centre would need to be decisively lower than her navel; a circle centred on her navel would chop her off her legs just below the calf. And, rather than the ‘ideal’ Vitruvian square, a rectangle would be needed to circumscribe her height and arms outstretched.

Professor of Exercise Science Kevin Norton and his colleagues, in their anthropometric study, compared Barbie to anorexics, fashion models and ordinary women, arguing that her chest size, for her height, is not abnormal but that her waist, hips and limbs are. It is in the ratios of one body part to another where the disproportion of Barbie is extreme: of waist to hips and, particularly, waist to chest.6

Mattel countered that Barbie’s extremely narrow waist was a consequence of being unable to minimise the thickness of fabric and fastenings, so that when she is dressed, the narrow waist is filled and she no longer looks out of proportion. Given that the Greek temple is well-known for distortions that are generally understood to correct for optical illusions, in this light Barbie’s proportion distortion might be considered within a certain architectural ‘character’.

Judgements on the doll undressed are not appropriate because Barbie was never meant to be naked; she was always to be clothed in the latest fashion. According to Barbie Media, Barbie maintains her sales position because she is “in tune, in time and always in fashion”. Not for nothing did the winners of the American Institute of Architects Barbie Dream House™ competition, Ting Li and Maja Paklar, centre their design around a four-storey high glass circular closet and shape the rails in the double helix of DNA. Barbie may be plastic, but her DNA is fashion clothing.

The perfection of Euclidean geometry which encapsulates Vitruvian Man is seen as less interesting in architecture these days, so perhaps Barbie’s disproportionate (and clothed) body might be a more fitting symbol for twenty-first century architecture.

- Translation/paraphrase from Henry Wotton The Elements of Architecture, 1624. http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Vitruvius/home.html[↩]

- Barbie: I Can Be “Amazing Architect“[↩]

- Jessica Lane, ‘The Audacity of Architect Barbie’.[↩]

- Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, de Architectura, Book III, Chapter 1.[↩]

- Helga Dittmar, Emma Halliwell and Suzanne Ive, ‘Does Barbie Make Girls Want to Be Thin?,’ Developmental Psychology 42, no. 2 (2006), 283–292.290.[↩]

- K. I. Norton et al., “Ken and Barbie at Life Size,” Sex Roles 34, no. 3-4 (1996): 293.[↩]