Karen Burns’ essay “Women in Architecture” published in the July 2011 issue of Architecture Australia, gives an overview of the state of play and the issues facing women in Australian architecture, along with an outline of the research project. It generated a large anecdotal response. Building on this discussion, we have asked a number of architects, men and women, to use Karen’s essay as the starting point for their own reflections.

The architectural office is one of the three most important sites of architectural production, although when we discuss architecture we most commonly refer to the building site. The office is far less visible but equally important. The office houses, structures and organizes architectural labour, processes of decision making, communication and negotiation. Both sites are linked to the third key site of architectural production: the architectural media in all its diverse forms (exhibitions, blogs, magazines, conferences, academia, etc.). The representation and discussion of architects and buildings in this media sets terms of definition, judgment, circulation of buildings and profile, and, of course, may do this in gendered ways – some negative, some positive. Our project examines the office as a crucial site of production and representation.

There have been many studies of women’s representation in the architectural media and studies of women architects and client groups, but fewer inquiries into the everyday culture of work beyond statistical analysis and anecdotal reportage. Importantly, our research introduces a number of key issues and methods and moves beyond interview data into workplace analysis.

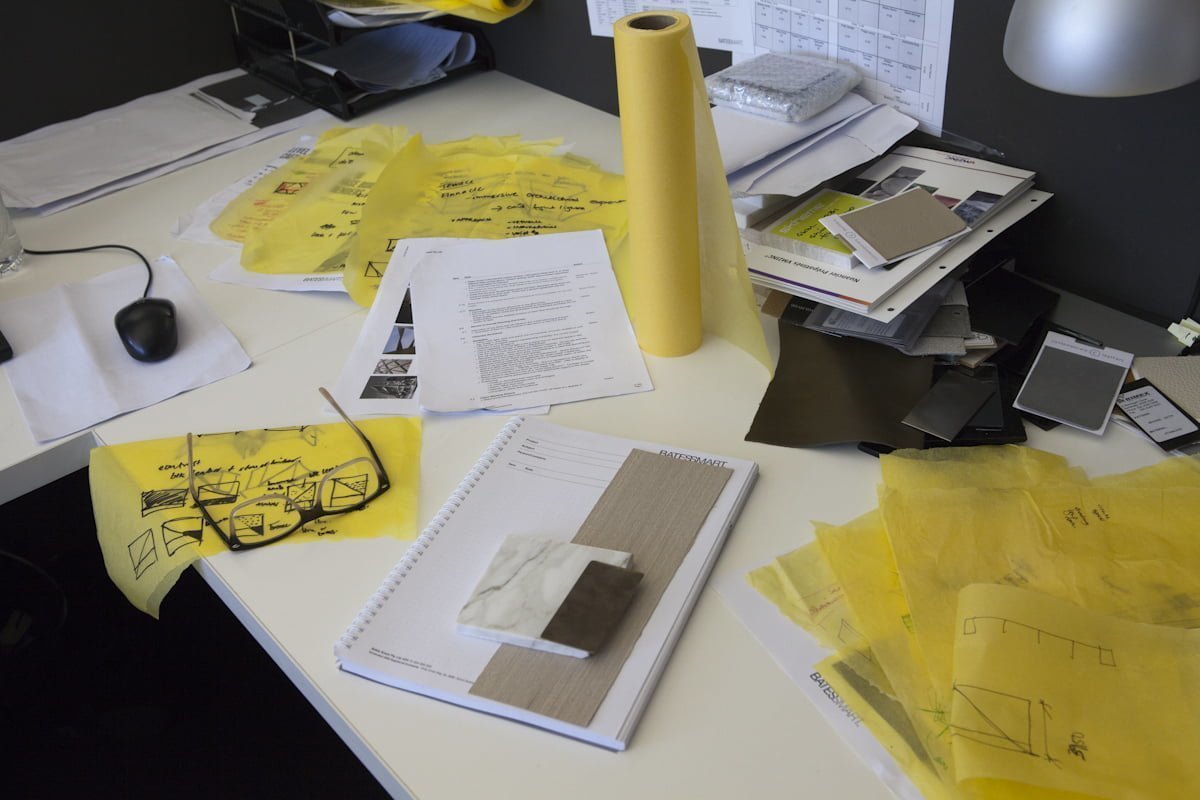

Our study works with three large architectural practices who are both partners and case studies for our investigation into work culture and women: Bates Smart Architects, BVN Architecture and PTW Architects. These three firms are keenly interested in helping us develop a best practice model. One of our partners, Bates Smart, has an excellent track record in appointing women to senior positions. Another, BVN Architecture, is “explicitly engaged with processes of innovation and collaboration in their architectural production and are keen to bring the same attitude to bear on the management of their staff.” The other practice, Peddle Thorp and Walker, based in Australia and China offers an insight into cultural difference and how this may affect workplace culture and gender dynamics.

Our project is an ethnographic study of the architectural workplace. It embeds a researcher in five architectural offices across Australia and one in China. Through participant observation and the collection of other data through interviews and other formats we will observe and analyse how gender operates in the architectural workplace.

Using the culture of these offices as a study, we seek to understand how gender and workplace intersect in positive ways and in ways that may slow women’s career progression. We aim to map women’s participation in the profession and to understand why women are under-represented in senior management. We will look at both barriers and good employment practice. We aim to argue the case for the social, economic and architectural benefits of a gender-diverse workforce. Finally, we will be developing a national policy on equity and diversity for the Australian Institute of Architects.

Why?

When this research project is publicly discussed, people ask about its focus, wondering why we are interested in the large-scale office and particularly in women’s accession to senior positions. Why aren’t we focusing on buildings designed by women or women client groups or small practices? All of these studies need to be undertaken. Big offices are large enough to study women’s ascent through the career ladder. However, our project springs from an issue common to many offices, large, medium and small: the diminished number of women in the profession, particularly in senior roles. Studying the workplace allows us to consider why fewer women appear in the lists of registered architects compared to their student numbers in architectural schools. This problem has been noted by at least three architectural institute studies from the UK, Canada and Australia.1 It is known as the gap between training and opportunity. After graduation comes the work experience.

Retention

The education/profession disparity was identified some years ago. The foreword to a 1996 North American anthology The Sex of Architecture observed:

For the last two decades, they (women) have constituted nearly half the enrolment in this country’s most prestigious architecture programs – programs from which they consistently graduated at the tops of their classes. Yet in 1995, only 8.9% of registered architects and 8.7% of tenured faculty in the United States were women.

Fifteen years later, women comprised 17% of US registered architects (an increase of 8.1% – although Garry Stevens suggests that if we include unregistered professionals it may be closer to 24%).

The gap between training and opportunity has been noted in Britain and Australia as well. Data collected by Paula Whitman in 2002 indicated that women comprised 43% of architecture students in Australia. Their representation in the profession varied from state to state: 11.6% of registered architects in Queensland, 15% in New South Wales. Victoria has the highest proportion of women registered at 18.2%. In a UK survey from 2000, 13% of practising architects were women. Women comprised 38% of students and 22% of teaching staff.

Other professions and architecture

Women’s progress to proportional representation in the professions is slow everywhere. The Royal Architectural Institute of Canada 2003 Report offered a useful comparison between professions. Women in architecture comprised 18% of the profession compared to civil engineers at 8%, general practitioners at 30%, dentists at 22% and lawyers and notaries at 31%. Retention is a problem in all these areas.

The problem of proportional representation has other complexities beyond the question of parity between the classroom and the office. The numbers of women in the profession don’t seem to be accelerating at the pace we might expect. If North America has had equal numbers of male and female architecture students for thirty-five years, why have women only achieved 17% of the registered profession at the end of thirty-five years? In Australia we are very unlikely to meet a 1996 RAIA prediction that by 2018, women would form 40% of the profession – even though in 2010 women formed 44% of the Australian architectural student population. We also need the most up to date data, which our study will collate.

Examination of gender representation in the architectural profession reveals another curiosity: only very small numbers of women occupy senior positions. (Whitman reported that less than 1% of registered architects in Queensland in 2002 are directors of architectural companies.)

The statistics from the architecture profession confirm a broader social trend within professions and business. Many of these areas report a gap between women’s access to education and subsequent professional achievement. Local data confirms disparities of seniority in other professions. The Victorian Women Lawyers association reports that across 2008 and 2009, almost 50% of barristers signing the law rolls are women. However, women form only 22% of lawyers at the bar (that’s 421 women). Women comprise about 9% of senior or Queen’s Counsel lawyers in Victoria (20 women compared to 274 men). As widely reported earlier this year, in Australia in 2010 women represent a mere 9.8% of directors in the top two hundred company boards.2

Another discovery from the statistical data is that women earn less. The Royal Architectural Institute of Canada 2003 Report records that full-time women architectural workers earn 82% of the salary of full-time male workers in architecture, and part-time women architectural workers earn 62% of the salary of part-time male workers in architecture. Comparative professions also report the earning equality gap. Full-time women civil engineers earn 80% of male salaries, general practitioners earn 70%, dentists earn 66% and lawyers/notaries earn 68%. The reasons for this gap are complex but surely involve the over-representation of women at more junior levels of professions and management, which means lesser earnings.

There is also a gendered difference in the extent of labour market participation. Put simply, women are over-represented in the part-time workforce and this limits earnings and career opportunities. A 2004 UK architectural survey reported that two-thirds of women in architecture had worked part-time at some stage.3

Once again labour patterns in architecture can be contextualized within broader social trends. In 2010, Melbourne University’s Graduate School of Education released a twenty-year longitudinal study, “Gen X Women Graduates.” Now aged in their mid-thirties, “only 38.4% of women with university degrees worked full-time, compared to 90% of university educated Gen X men.”4 Again the reasons for women’s over-representation in part-time work are complex.5 It’s been argued that women move between full-time and part-time work over the course of their lives “according to their work histories and positions in the family life cycle.”6

From the statistical data alone we can note women’s greater representation in different work experiences: across retention rates, lesser earnings, more junior positions and the part-time work force. Looking closely at the dynamics of workplace culture might help tease out some of these demographic figures.

Workplace culture

The architectural workplace organizes labour and production – but the office can also be analysed as a cultural system. Dana Cuff first interpreted the architectural workplace within an anthropological understanding of offices as key sites for the “culture of architectural practice.” In her fine study, Architecture: The Story of Practice, she argues that each office has a management style that includes “the norms and values appropriate to the office, the patterns that projects and teams follow, and the rewards and incentives for workers.” For Cuff the office’s cultural system also includes “the office’s dialect, mores, activity patterns, power structure, and roles.” These events and gestures provide a portrait of an office’s culture – and from here we can generalize patterns of behaviour and values beyond individual workplaces.7

If a workplace is a cultural system we might expect that other components of culture bob up there. Gender surely is one of these. A number of sociologists of work have observed that the workplace is gendered. The 2010 Monash University “Social inclusion at Monash: gender equity strategy 2010–2015” explicitly described organizations as sexed cultures.

Organizational norms continue to reflect masculine experiences, values and life situations. These norms contain unquestioned assumptions about the value of specific types of work practice and achievements. Normative practices continue to reward linear employment path, the freedom to work long hours and prioritizing work of any other commitment.8

The report notes three things as gendered norms: linear employment, long hours and the absolute prioritizing of work. Examining these things may help us to understand the demographic disparity between male and female architectural workers. Data on why women leave the profession can be correlated to the Monash report in order to see what, if anything, is distinctive about the gendered experience of architectural workplaces.

Why do women leave architecture?

An English study by Fowler and Wilson reports that young women leave the profession due to lengthy hours, slow career progression and low pay.9 A 2000 Québécois study produced one of the few comparative accounts of male and female exits from architecture.10 Men departed for the same reasons, including low salaries and economic downturn. Like women, they were dissatisfied by “narrow” or restricted definitions of architecture and also left to pursue alternate careers in related fields. However, this information acquires more complex detail when we examine the list of reasons given by the RIBA 2003 report “Why Do Women Leave Architecture?” It lists fifteen factors:

- Low pay

- Unequal pay

- Long working hours

- Inflexible/un-family-friendly work hours

- Sidelining

- Stressful working conditions

- Protective paternalism preventing development of experience

- Limited area of work

- Glass ceiling

- Macho culture

- Sexism

- Redundancy and/or dismissal

- High litigation risk and high insurance costs

- Lack of returnee training

- More job satisfaction elsewhere

Of these fifteen reasons, seven deal with forms of gender discrimination that limit work experience and advancement opportunities. A further three reasons deal with the family/work balance, which includes the issue of long hours and lack of returnee training. Thus ten out of fifteen reasons given for women’s exit from the profession are gender-based.

I want to discuss these within the context of research produced on gendered workplace practice. I’m going to focus now on a more detailed discussion of five issues: standard employees/standard careers, work hours, flexibility, returnees and finally sexism.

Redefining work

In 2006 the Australian Bureau of Statistics reported that 84% of Australian women aged 40–44 had children (I couldn’t find the data on men). Some researchers on workplace culture describe both paid and unpaid work patterns when analysing people’s labour – as Janet Walsh observes, paid and unpaid work impact on each other.11 Another labour market analyst noted the gender differential in the relationship: “Responsibility for children impacts on women’s and men’s paid and unpaid work. Time-use surveys reveal gendered impacts – work changes women’s paid and unpaid work much greater than time for men.”12

Before I discuss the impact of family caring responsibilities I would like to note that the Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission has declared that men haven’t been able to care equally for their families and this is an equal opportunity issue for men.

We will not be successful unless we ensure that men and women have the same opportunities to engage in paid and unpaid caring work. While we have come a long way in opening up opportunities for women in paid work, we have not had the same success in allowing men and women to care equally for their families. It is this second half of the equality revolution that this project aims to accelerate.13

A study titled 100% is underway and will survey Australian men about their attitudes to work/life balance.

As employment lawyer Juliet Bourke declares, “The argument we never engage with is the structure of work itself, who is advantaged by it and how they make their decisions.” When Monash University’s 2010 report observes that a masculinized workplace prioritizes commitment to work over all other commitments, how does family care fare in this model? Having a family even if you work full-time means you need greater flexibility around working hours, arrival and departure times and demands to be in the office.

One of the reasons given in the 2003 RIBA report for women’s exit from the profession was inflexible work places/unfamily friendly work hours. Let’s take a close look at the issue of work hours.

Hours

Some professions assume or demand long working hours more than others. A 2004 UK architecture survey reports that “without exception, every architect [male and female] portrayed architecture as requiring long hours of work in a highly competitive environment.”14 Dana Cuff argues that the architectural workplace is dominated by a “charette ethos,” beginning in architecture school. A 2000 Québécois study of architectural professionals identified “the cult of overtime.” It seems that economic uncertainty, at least in Britain, may have intensified this work habit. The 2004 RIBA report observed: “Periods of economic and employment uncertainty … have created a climate where it is necessary to demonstrate high commitment and to some extent, ‘presenteeism’ for the salaried architects.”

These salaried workers are described as “overworkers.” Employees didn’t see this demand as positive; “they see the balance of rewards to themselves as negative due to the economic necessity to work or fear of job loss.”15 The RIBA study notes a sharp divide between salaried architectural workers and employers (principals of practices or directors of solo practices) over this issue of required overwork. Does it matter? Can you opt out? You can in some ways, but women in architecture report a penalty (other than long hours). The ability to do overtime is seen as a key factor in getting ahead, according to 67% of the women in architecture surveyed by the 2005 Whitman/RAIA report. It seems that architecture mirrors this longstanding assumption of the corporate world where managers substitute quantity for quality in their evaluation of work.15

Can we address this issue or do we assume that long hours are part of the fixed, eternal structure of architectural production? We can look to other workplace models, discovering, for example, that business is already moving on this issue. Employment lawyer Juliet Bourke observed last year, “The sort of people who can do these eighty-hours-a-week jobs are basically people who don’t have anything else in their lives … Research shows that it’s not good for business to have highly stressed ‘monocentric’ employees.”

I would argue time is an economic resource. It is not endless and needs to be managed to produce profitability and employee health and happiness. Another researcher and myself are going to undertake a study of medium sized architectural practices to see how time can be managed for best business practice. We will look at profitable, expanding firms that have strong boundaries around weekend work and lengthy days. They work smart not long.

Furthermore, we can re-examine the demands for presenteeism in architecture under the impact of the digital communications revolution. Does everyone need to be in the office all these hours? Could parents with children or other carers partly work from home? We have electronic file sharing of documents. We have globally distributed architectural offices. Can we evaluate work as productive output and not hours on the office floor? Rethinking these issues in an architectural context would put us on par with other researchers and consultants rethinking the structure of work.

The question of working hours can also be thought about in another way – as the difference between part-time and full-time work. I’ve already pointed out that only 38.45% of current Gen X women full-time. The 2004 RIBA study noted that two-thirds of women in architecture report working part–time at some stage. As well as the issue of the availability of part-time work, we might wonder about its financial differential. You may remember that in the RAIC 2003 study women part-time architectural workers earnt 62% of male part-time earnings. (Is this because part-time male architectural workers are senior retired practitioners or highly prized freelance consultants?) We need more gender comparative data in architecture.

Part-time work / non-standard careers

The question of part-time work and absences from the structured, paid labour market, perhaps predominantly due to childbirth and child rearing, have further impacts on women’s careers. The 2010 Monash University “Social Inclusion” document noted that linear career paths were part of the masculine norms of the workplace that may provide gendered work patterns. Discontinuities in paid employment produce stop/start or non-standard CVs and may then produce different career paths.

What happens when your last project was four years ago? Paula Whitman’s 2005 study of 550 women in architecture notes: “Women suggested that good performance on previous projects, compatibility with senior management and office culture, as well as an ability to lead and manage staff are the key factors in career progression … Given the discontinuous nature of women’s careers, this emphasis on good performance on previous jobs has the potential to be problematic.”

Janet Walsh in her study of part-time workers observes, “more part time work experience increases the probability of remaining in part time rather than a full time job.” (There are voluntary and involuntary reasons for this.) One important further issue is the question of returnees – I don’t have data on this for the profession although only a third of women architects in the Fowler study in the UK reported having access to maternity leave. There is a much larger question of what happens to women when they return to work and our study may be able to see some of these patterns. Women move between part-time and full-time work.

Towards a conclusion

These kinds of factors can produce accumulative disadvantage in women’s careers. US professor of psychology Virginia Valian argues that “success is largely the accumulation of advantage, the parlaying of small gains into larger ones.”16 Women experience small disadvantages that add up.

We might imagine that these small things are the factors we’ve already examined, such as part-time work, or the inability to do overtime. However, this focus on women with children to explain women’s glacial progress doesn’t allow us to account for two other things. Childless women experience slower rates of progress than men – what’s disadvantaging them? And Valian asks how we account for workplaces where “nothing seems to be wrong, where people genuinely and sincerely espouse egalitarian beliefs and are well intentioned, where few men or women overtly harass women.” These are sobering questions which suggest that gender perception also plays a part in constructing women’s different work experience.

Valian proposes that everyone, male and female, shares a “gender schema.” She is not accusatory or blaming, but analytical and concerned with the structure of human behaviour. She argues that human beings categorize, and that we prefer to have fewer rather than more categories when we are categorize. Our gender schemas are not necessarily accurate and the inaccuracies are not necessarily sexist, but “sexism steps in when values are attached and prescriptions imposed.” She uses a number of experimental psychology studies to show that we (men and women) are likely “to overvalue men and undervalue women.”17 All of these affect “perceptions of competence, the ability of women to benefit from their achievements and to be perceived as leaders.” We are all participants, no matter how well intentioned, when we assess the lecturers in front of us, our employees, our prospective employees.

This effect can be countermanded by conscious strategies, policies and checklists, workplace mentoring, role models, promotion structures, development programs, transparency of promotion criteria and pay structures .

We have examples of workplaces that have done this, such as the medical schools at John Hopkins and Monash. With conscious policies and procedures, they raise the level of women’s participation and promotion and offset the creep in unconscious disadvantage.

Architecture’s image

The 2003 RIBA report offers a very blunt comment on the image of architecture in society. It argues that a more gender, racially and ethnically diverse architectural profession could have a positive impact on the image of architecture. The report claims (but without concrete evidence), “The profession does not have a particularly positive image and if it does want to move forward and change this, part of the exercise is to better reflect society rather than appearing arrogant, aloof and unaware of social shifts.” Institute reports from Britain, Canada and Australia recommend producing more diverse narratives of the profession (RIBA) or different award criteria and exhibitions around the diversity of contributions made by different team members (RAIA, 2005), not just to profile women in architecture but to suggest something about the kinds of professional skills possessed by architects, “to raise the image of architects” (RAIC, 2003). This is where the third site of architectural production comes in.

Mirroring our client groups

Having a best practice model for retaining and fostering women’s career progression could have a benefit for practices who do this. They will mirror some of our client groups, many of which are engaging in this activity. Our businesses need to be seen to mirror their policies.

The business model

Some researchers and reports have been formulating the case for gender diversity as the “business benefits of social inclusion.” I’m most familiar with the business case in the argument mounted in the UK government-commissioned report on women on corporate boards. The February 2011 report “Women on Boards” registered the statistics: women currently make up 12.5% of corporate boards of FTSE 100 companies. The report notes: “Evidence suggests that companies with a strong female representation at board and top management level perform better than those without and that gender diverse boards have a positive impact on performance.” They measure operational and share price performance, returns on sales, equity and capital. (E.g. companies with more women on their boards were found to outperform their rivals, with a 42% higher return in sales.) As well as performance and governance issues, the report argues for the need to access the biggest talent pool possible.

The report doesn’t claim that gender-diverse boards perform better because women are inherently more highly skilled or intrinsically ethical. It argues that boards are more successful when they can draw on a broader range of skills, perspectives and experiences. The report also identifies the danger of single-sex boards operating through “group think.” Although an appalling misuse of the English language, the term does identify the dangerous culture of assent when organizations are demographically homogeneous. A questioning or dissenting voice may prompt further consideration of the impact of decisions. That’s not a gender-specific trait.

Our research project proposes outcomes in two categories, policy and communication. Policy outcomes include a national policy on gender and diversity for the Australian Institute of Architects and developing strategies for retention, promotion and reduced discrimination. Virginia Valian’s work on the gender schema demonstrates that all of us, both male and female, make instinctive and different judgments of men and women which can act to disadvantage women, particularly when women are considered for leadership roles. Conscious policy-making and monitoring of gender issues can help offset these biases. Communication of our findings will also raise the visibility of women in office practice and contribute to scholarship. Developing a best-practice model from the research results offers a blueprint for Australian architectural business seeking to be in step with corporate and government clients on issues of social inclusion and well-rounded employees. We thank the architectural practices and the Institute for making this research project possible. They are offering leadership in fostering a best practice for women’s retention and seniority study and, in so doing, are remaking models of leadership.

- See RIBA, 2003, Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, 2003 and the then Royal Australian Institute of Architects, 2005 study.[↩]

- The Age, 19 September 2011.[↩]

- Bridget Fowler and Fiona Wilson, “Women architects and their discontents,” Sociology, February 2004, 38 no 1.[↩]

- The Age, 11 July 2010.[↩]

- See Janet Walsh, “Myths and counter-myths: an analysis of part-time female employees and their orientations to work and working hours,” Work, Employment & Society, June 1999, vol 13 no 2, 179–203. A study of the banking industry.[↩]

- Walsh, “Myths and counter-myths,” 1999.[↩]

- Dana Cuff, Architecture: The Story of Practice (MIT Press, 1992).[↩]

- ”Social inclusion at Monash: gender equity strategy 2010–2015,” Monash University, 2010.[↩]

- Fowler and Wilson, 2004.[↩]

- Annmarie Adams and Peta Tancred, Designing Women: Gender and the architectural profession, (University of Toronto Press, 2000).[↩]

- Janet Walsh, “Myths and Counter-Myths: An Analysis of Part-Time Female Employees and Their Orientations to Work and Working Hours”, Work, Employment & Society, 13, 2, 1999.[↩]

- Marty Grace, “Australian women’s and men’s income by age of youngest child,” Journal of Business Systems, Governance and Ethics 2 no 2, 2007.[↩]

- HREOC (Australia) 2005 report.[↩]

- Fowler and Wilson, 2004. My addition in parentheses.[↩]

- Val Caven, “Constructing a career: women architects at work,” Career Development International, 9 issue 5, 2004.[↩]

- Virginia Valian, “Sex, Schemas, and Success: what’s keeping women back?”, Academe, Sept/Oct 1998, vol 84 no 5, 50–55.[↩]

- Virginia Valian, “Beyond gender schemas: improving the advancement of women in academia,” Hypatia, Summer 2005, vol 20 no 3, 198–213.[↩]

1 comments

A. Wilson says:

Jul 3, 2012

On the topic of gender schema, a recent article in The Atlantic reports on recent research that found that men’s attitudes to women were strongly influenced by their marital status: “We found that employed husbands in traditional marriages, compared to those in modern marriages, tend to (a) view the presence of women in the workplace unfavorably, (b) perceive that organizations with higher numbers of female employees are operating less smoothly, (c) find organizations with female leaders as relatively unattractive, and (d) deny, more frequently, qualified female employees opportunities for promotion.”