For the past decade, US architect Katherine Williams has been researching and reporting on the licensure status of African American women architects, with numbers doubling over that period.

In 2010, I was on the precipice of finishing my architecture registration exams and becoming a licensed architect. It was the culmination of a journey that started when I first met an architect in my elementary school years and decided that the profession was interesting and something I wanted to pursue.

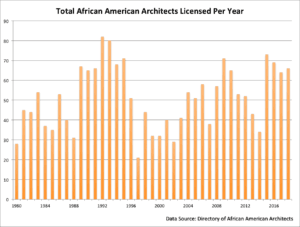

In 2010, I started corresponding by email with Dennis Mann, one of the editors of the Directory of African American Architects, about ways to give a historical view of the numbers of the people in the directory. The website lists all of the African American architects who have reported on their licensure status in the US. Personally, I was curious about the trends of the numbers: what years did the most architects get licensed? What affected the up and downs of the numbers? Were we doing any better in 2010 than we did in 2000? And so on.

In the US, architects are licensed by each state. To earn their license, candidates must earn an accredited degree, complete and document experience hours in a variety of topics and then complete an exam. Once licensed in a state, architects can get reciprocal licensure in additional states.

The Data

Dennis sent me some of the data and I started creating charts. This was before infographics were so commonly used, but as a person in a visual profession I knew the importance of communicating using graphics and not just words.

Since that time almost 10 years ago, I request data annually from Dennis and try to do some comparisons and rudimentary analysis about the status of African Americans in the profession. I have expanded and, in some years, looked at the comparison with economic trends, world events, and also NCARB’s annual report on licensure (NCARB is the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards, which creates and administers the licensing exam). I have put these charts and information into an annual blog post to give people a picture of the actual numbers and as a tool to encourage those who are in the process to continue their journey and increase the numbers.

Dennis Mann, Brad Grant and the University of Cincinnati have been stewarding the Directory project since the early 1990s. It has become a valuable asset and a source of pride when one gets listed. They regularly get inquiries about lists for other groups because people want to know how many of their particular racial, ethnic or other group outside the white, hetero, male stereotypical picture of an architect, are licensed architects. It has only been since 2015 that NCARB started including racial breakouts in their annual report. Before that, the demographic data, regarding who was testing and in the NCARB pipeline, was virtually hidden. That report can now also be used as a tool to see where the profession is on increasing diversity in the benchmarks that NCARB tracks.

Findings

Over the years, we can see from the charts that there are spikes and valleys. Many of these are the result of outside forces. NCARB’s exam updates precipitate a lot of people trying to finish as they want to avoid moving to a new exam. We see this in the numbers from 1994 and 1995 as there was an increase and then a drop in 1996. An even larger decrease occurred in 1997 as the full digital exam was activated. In 2009 and 2010, the change from exam version 4.0 to 5.0 drove many to try to finish before the exam changed, as content was being rearranged and a new exam format was being introduced.

NCARB introduced a five-year rolling clock on exams in 2006. Scores are only valid for five years. This forces candidates to not delay taking their exams. If extenuating circumstances occur, candidates can ask for a reprieve on this rule. However, this does mean that people are not remaining in the pipeline for ten years or more as was the case before this policy was implemented.

Another outside influence is the economy, and indirectly the political climate. Recessions affect graduates entering the profession. If firms are not hiring because there is less work, full graduating classes may take a longer time to engage in taking exams. The recession of the early 1990s probably affected the number of people that would have been testing in the mid to late 1990s. The recession of 2008–10 affected who was eligible to test in the 2011–14 years. This may be less of a factor going forward, as in most states candidates no longer have to complete the required experience hours, approximately three years, before testing. Exams can now be taken at the same time as interning and some schools are now piloting integrating the exams into their curriculum. If interns are looking to firms to help fund their exam fees, their employment status also will influence when they take exams.

This year we are already seeing the pace slow in the number of African American getting licensed and reporting. That is a little concerning since the economy is still relatively positive for architects. It may take a year or two before we have hindsight to recognise what factors are influencing this year’s numbers.

One of the positives that this tracking showed is the number of African American women architects. In 2007, there were only 200 licensed African American women architects. In 2017, that number reached 400 women and topped 450 in 2018. What had previously taken about 60 years to achieve – going from zero to 200 – was repeated in ten years. This speaks to the fact that more women are graduating from architecture school and more women are pursuing opportunities in the profession and seeking leadership roles. This also demonstrates that more women may either be getting support in their firms to get licensed or are looking to start their own firms, which requires licensure.

Conclusion

Data is important. Without it we can have stories and anecdotes but we do not have a complete picture of what is happening. We need the data to tell the full story. My reports are one piece to add to a fuller picture of where the architecture industry is regarding creating a more inclusive profession.

Katherine Williams, AIA, NOMA, LEED AP is a licensed architect in Northern Virginia. She has had a varied career path from traditional architecture firms to community development to managing commercial construction for a general contractor. She has served as chair of the AIA Housing and Community Development KC advisory group, the NOMA magazine editor, and was an Enterprise Rose Architectural Fellow in San Francisco. She was a 2016 recipient of the AIA Virginia Emerging Professionals award. She writes at katherinerw.com.