So, now that we have the research, what do we do? Naomi Stead and Justine Clark outline the programs and tools for a more equitable profession.

The profession finds itself in a rare moment of promise: a moment full of potential to change things that have haunted and held back the profession for thirty years or more.

We want to make the most of this moment. To do so, our research team has provided a strong evidence base demonstrating the fact of gender inequity in Australian architecture, offered expert analysis and identified “best practice” models. But we also aim to leverage this evidence and analysis to have real impact – to actively encourage change. We do this by building awareness and understanding, by offering realistic, practical suggestions and by encouraging individuals, practices and institutions to each step up and make a difference.

The evidence base was developed using methods ranging from the fairly conventional to the experimental. A new, thorough statistical picture of women’s participation in the profession is complemented by more innovative approaches, such as visual research undertaken by Naomi Stead and the ethnographic fieldwork Gill Matthewson has undertaken within three architecture practices as part of her PhD – an uncommon approach within architecture.

Communities of interest

The project is also unusual in that it treats the architectural community as active contributors to the enquiry, not simply as the subject of the study. Firmly grounded in the rigour of academic research, the project moves beyond this to make new spaces for discussion and debate within the wider architectural community. We have invited commentary from a broad range of people, expanding the topics covered and reflecting the research findings back through the lens of practice.

This was partly a matter of tactics – we were aware that there had already been a number of excellent reports on women in Australian architecture, each of which had made achievable, important recommendations. However, few, if any, of these were acted on. We realized that to maintain momentum there needed to be many voices from many directions. We became activists and advocates as well as researchers and scholars.

This website has played a fundamental role in this and has been highly effective in developing what American critic Alexandra Lange calls “communities of interest.” Launched in May 2012, Parlour quickly attracted a high level of interest – at the time of writing it has had well over fifty thousand visitors from more than three thousand cities across 172 countries.

Parlour tapped into a current of concern that had previously had no outlet. It allowed many women to realize that they were not alone in their experiences, and to recognize these as part of larger structural issues. It allowed many men to say that they, too, wanted change in working conditions in architecture. As the site received more and more traffic, it became apparent that such a thing had been missing within the architectural community globally, and that the discussion we were trying to encourage – informed, reasonable, productive conversations about equity – were sorely needed everywhere.

It also became apparent that the problems faced by many women in architecture are closely tied into larger workplace and practice issues that go to the heart of the profession’s ongoing viability. Our first public event tackled this head-on, arguing that a more inclusive profession would also be stronger and more sustainable.

Transform: Altering the Future of Architecture was a one-day symposium that positioned women at the centre of the discussion of the profession’s future. Numerous panellists spoke frankly about challenges and opportunities in shifting how architectural work is managed and valued. They showed that change is possible – that there are other ways to operate successfully in architecture that expand the diversity and possibilities of architectural practice. Transform reinforced that our community – one of engaged, thoughtful, hopeful individuals looking to make change – is the profession’s greatest resource.

Policy

Traditional institutions and conventional workplaces – the sites of the production of much architectural culture – also need to change if we are to move towards a more equitable profession. This change is, in itself, a radical project.

One particular project aim was to assist the Australian Institute of Architects to draft a gender equity policy. After much hard work by research team members and the Institute Working Group (chaired by Shelley Penn), the policy was adopted in December 2013. This formally acknowledges, and aims to redress, the underlying structural issues that generate gender inequity in architecture. Its scope covers both the Institute’s internal processes and women’s broad participation and “ownership and leadership” in the profession. Future action is guided by ten clear principles.

Of course, policies can be merely symbolic documents, a way of paying lip service in a document that, after an initial fanfare, is tucked away on a shelf to gather dust. But the signs are good so far. A new, national committee has been charged with implementing the policy and has a mandate for change. It will recommend initiatives and programs, and will report on progress to national council and the membership. This is a serious committee, which is seemingly being taken seriously. If it works, it will be a powerful force for good.

Equitable practice

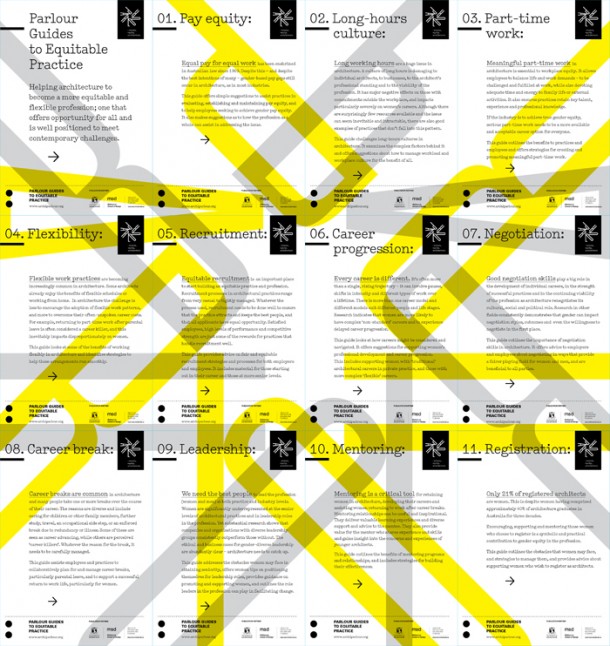

We have also produced our own direct action initiatives, in particular the Parlour Guides to Equitable Practice. Addressed to practices, employees and the wider profession, the Parlour guides outline the key issues facing women in architecture and provide positive, productive strategies for change. Combining our research findings with precedents in other fields, the guides were developed through an exhaustive consultation process with the profession.

From ensuring pay equity to combating the culture of long hours, from the provision of meaningful part-time work to developing skills in negotiation, from equitable recruitment to a culture of flexibility – the guides provide practical tools enabling women and men, employees and employers to work together for the benefit of all.

Our activism is focused on community building and on incremental change. We aim for positive, pragmatic advocacy that recognizes the real difficulties in managing and sustaining any architectural practice, but that also promotes the wellbeing of individuals in their work lives and the professional benefits that this brings. We seek to build consensus, because only the collaborative effort of women and men working together will make a difference.

Ours has been a very ambitious project – we have aimed for nothing less than the transformation of architecture to become a more diverse, sustainable, resilient and equitable profession. But this ambition must be shared, because ultimately real change must come from within the profession. If there was ever a moment to grasp the opportunity for change, it is now.

Note:

First published in the AA Dossier: The State of Gender Equity, Architecture Australia vol 103 no 5 (September/October 2014) and also available online. Read the other pieces in the dossier here.