How can we challenge the ways that architecture represents and perpetuate certain gendered identities? In Part 1 of her essay Lori Brown explores architecture own disciplining methods within the broader social and political contexts.

Introduction

I am interested in, and passionate about, evolving our discipline – both in the academy and in practice – and challenging the “disciplining identities” of architecture. This commitment has developed from several ongoing efforts, including my first book, Feminist Practices: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Women in Architecture; a series of public roundtable discussions that expanded several of the book’s larger themes; and the resulting women’s organisation ArchiteXX, which I co-started and now co-lead in New York.

This essay is part of my ongoing research into organisations that are successfully changing the dynamics of other historically male-dominated professions; research that will help develop ArchiteXX’s own efforts. As I began to look outside of architecture I found far more interesting and inspiring groups that are making a difference their respective disciplines.

I begin with a few questions for you, the reader, to ponder:

- What is the identity of an architect?

- What is the identity of an interior designer?

- What does is mean that, in the US, 70% of interior designers are women? And that women comprise less than 20% of licensed architects?1 What do you think are some of the effects of these statistics?

- To what extent do you believe gender effects any aspect of your life?

Your responses to these questions will help you locate yourself within the broader discussion about the influences gender has on these design disciplines’ self-identities.

This essay discusses several current events, which provide a bigger context to help demonstrate how gender differences impact our social and cultural wellbeing, and outlines how the discipline of architecture has historically represented and perpetuated certain gendered identities. Drawing on research into the broader implications of gender for the advancement of women’s careers, I then discuss what it means to be a woman in the workforce. Part two of the essay highlights inspiring models outside of architecture, which we might draw on as we seek to shift our own discipline.

Contextualising: a few examples

There is a movement afoot. A critical mass is speaking louder and louder, gaining traction across a broad spectrum of social issues. This is important because this critical mass has more power to affect and force change. I would like to highlight a few events that, I believe, reflect a cultural pulse that contextualises the broader issues and serves as important parallels to “disciplining identities”.

I must first begin with Australia’s former Prime Minister, Julia Gillard and her inspiring speech back in October 2012 when she called out the opposition leader Tony Abbott for his sexist, misogynist behaviour.2 As Barbara Pini, Professor of Gender Studies at Griffith University in Queensland, commented immediately after this event: “it was a watershed moment”.

“It’s incredibly significant to have a prime minister powerfully state that she has experienced sexism and even more powerfully state that she will refuse to ignore it any longer … That the sexism which is so deeply embedded in the Australian body politic was named may give some women license to express and seek to counter the sexism they have experienced in their working lives.”

Representation

Back in January of 2012, the Obama administration mandated “most health insurance plans must cover contraceptives for women free of charge…” refusing the Catholic Church’s proposed religious exemption.3

Less than one month later, following strong backlash from religious groups, the administration announced a compromise requiring the “insurer – rather than the employer – to provide contraceptive coverage…”4 Obama’s contraception compromise precipitated a House of Representatives Oversight and Government Reform Committee hearing. One of the most distressing and outrageous results of the first hearing was that the coterie of witnesses comprised five men of various religious and academic affiliations. Women in support of contraceptive coverage were not allowed to testify.5 As committee chairman Representative Darrell Issa argued, “the hearing is not about reproductive rights and contraception but instead about the Administration’s actions as they related to freedom of religion and conscience.”6 Committee member Representative Carolyn Maloney (D-NY) asked, “What I want to know is, where are the women? … I look at this panel [of witnesses], and I don’t see one single individual representing the tens of millions of women across the country who want and need insurance coverage for basic preventive health care services, including family planning.”7 In objection, Representatives Maloney (D-NY) and Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-DC) walked out.6

Less than one month later, following strong backlash from religious groups, the administration announced a compromise requiring the “insurer – rather than the employer – to provide contraceptive coverage…”4 Obama’s contraception compromise precipitated a House of Representatives Oversight and Government Reform Committee hearing. One of the most distressing and outrageous results of the first hearing was that the coterie of witnesses comprised five men of various religious and academic affiliations. Women in support of contraceptive coverage were not allowed to testify.5 As committee chairman Representative Darrell Issa argued, “the hearing is not about reproductive rights and contraception but instead about the Administration’s actions as they related to freedom of religion and conscience.”6 Committee member Representative Carolyn Maloney (D-NY) asked, “What I want to know is, where are the women? … I look at this panel [of witnesses], and I don’t see one single individual representing the tens of millions of women across the country who want and need insurance coverage for basic preventive health care services, including family planning.”7 In objection, Representatives Maloney (D-NY) and Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-DC) walked out.6

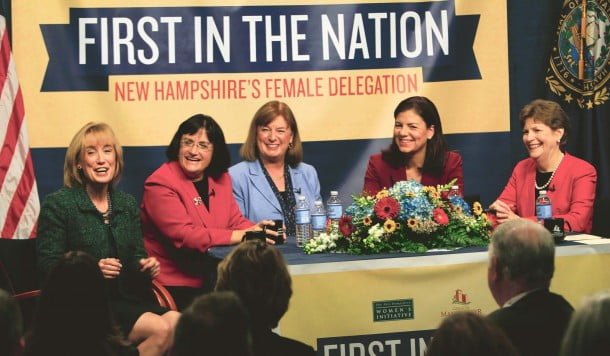

The 2012 United States Election for the 113th congress was a hallmark year for women in politics. As a result of that election, women now hold 98 (18.3%) of the 535 seats in the US Congress. Of these, 30 (30.6%) are women of color, 20 (20%) of the 100 seats in the Senate, and 78 (17.9%) of the 435 seats in the House of Representatives. As a comparison, to date a total of 293 women have served in the US Congress. This includes 33 women in the Senate, 250 women in the House, and 10 women in both the House and Senate.8

Additionally the state of New Hampshire became the first state to have an all female delegation where the governor, house representatives and senators are all women.

Additionally the state of New Hampshire became the first state to have an all female delegation where the governor, house representatives and senators are all women.

With the increase of women in the US Congress there have been actual spatial implications as well. Only three years ago the creation of a women’s restrooms adjacent to the House of Representatives floor was begun.9

Taking a closer look at the University of Melbourne in 2013, we find a mix in terms of gender parity among upper administrative levels. From the university’s website I was able to ascertain the senior office bearers are 9 and 15 men; the Office of the Provost has 13 women and 10 men; the Academic Deans fare the worst, with only one woman dean compared to 10 male deans; and the Faculty of Architecture is comprised of 11 women and 18 men.

Academic demographics

The data for US schools of architecture is quite revealing. According to the 2011 National Architectural Accrediting Board report (NAAB), those teaching architecture are far more often male and white across all levels of teaching. Full professors are 79% men and 85% are white; associate professors are 73% men and 79% are white; assistant professors are 68% men and 72% are white; and instructors are 70% men and 75% are white.10 The leadership of programs of architecture is even worse. There are currently 154 NAAB-accredited professional programs in architecture, housed in 123 institutions. Of these, only 22 deans are women – a mere 7% of all top leadership is female.11 Compare these numbers with recent NAAB student statistics – over 41% of students in accredited architecture programs are women and 43% of women graduate receiving an architecture degree.

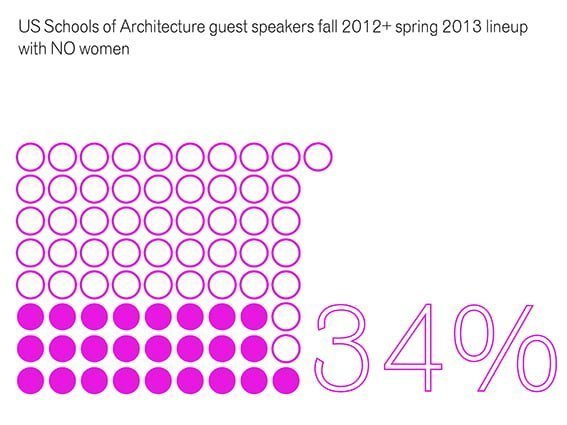

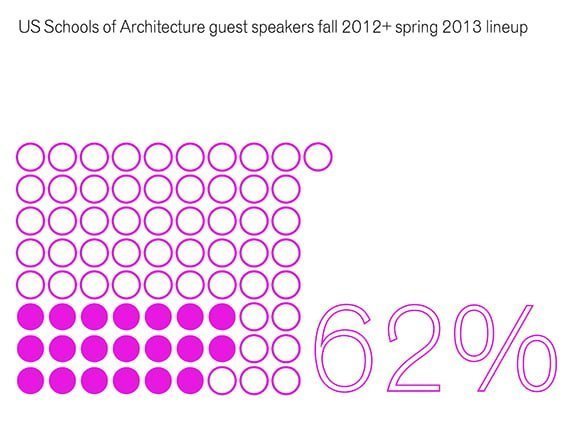

A school’s public events roster is also rather telling. Who are the invited speakers for lectures and symposia?12 My research assistants did quick searches for the past two years. Of the 73 schools they were able to locate information for, almost 62% of schools have either no women or only one woman invited as a public lecturer. Additionally, over one third (34.3%) have no women whatsoever as part of their public programming. This disturbing statistic demonstrates the perpetuation of gender discrimination within academia. How will female students and students of color realise they can be successful architects and designers if they do not see role models that look like them as part of leadership and public programming?

Why representation matters

All of these statistics illustrate a greater point – gender representations in a group matter. Research by Professor Tali Mendelberg and Assistant Professor Christopher Karpowitz into the impacts of gender parity in decision-making found that “female lawmakers significantly reshape policies only when they have true parity with men.”13 Their study of women in focus groups found that when women comprise [only] 20% of a decision-making body they have limited impact:

“Operat[ing] by majority rule, the average woman took up only about 60 percent of the floor time used by the average man. Women were perceived – by themselves and their peers – as more quiescent and less effective. They were more likely to be rudely interrupted; they were less likely to strongly advocate their policy preferences; and they seldom mentioned the vulnerable. These gender dynamics held even when adjusting for political ideology (beliefs about liberalism and egalitarianism) and income… But once women made up 60 to 80 percent or more of a group, they spoke as much as men, raised the needs of the vulnerable and argued for redistribution (and influenced the rhetoric of their male counterparts). They also encountered fewer hostile interruptions … In another study, [the researchers] pored through a sample of minutes from more than 14,000 local school boards and found that the pronounced gender gap in participation shrank sharply when women’s numbers reached parity – a real-world confirmation of [their] experimental findings.”14

We can extrapolate that, for example, if more women were part of the governance of the University of Melbourne, a wider range of concerns would be put forward and heard. The same can be argued for architecture.

One cannot deny that there has been progress in this area – there are now far more women in the workforce, far more women in architecture. But many, including myself, believe it has not improved nearly enough and that stagnation has occurred. As Linda Babcock and Sara Laschever write in Women Don’t Ask Negotiation and the Gender Divide, this stagnation suggests

“that we may have gotten as much mileage as possible out of the changes we’ve already made – and that new solutions need to be found if women’s progress is to continue. One of these solutions must be a change in society’s attitudes toward women who assert themselves. Another we’re convinced, will come from encouraging women to speak up for what they deserve – to recognize more opportunities in their circumstances, appreciate the value of their work, and ask for what they want.”15

I will speak more to this a bit later.

Awards

Within design fields, we award those we believe do the best work, are the most creative and are the most provocative.

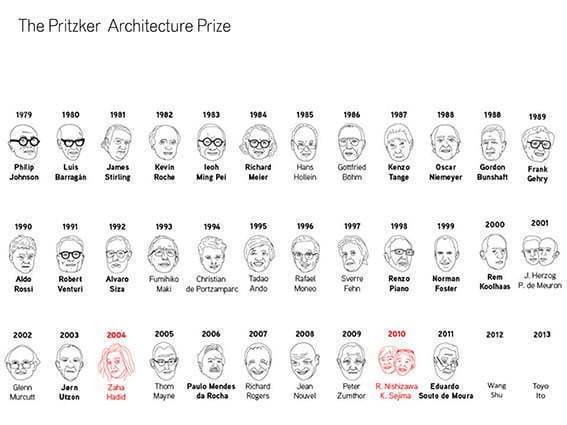

I’d like to mention Hilde Heyen’s critical analysis of the Pritzker Architectural Prize. Her essay “Genius, Gender and Architecture: The Star System as Exemplified in the Pritzker Prize” explores the “sexist bias in awarding the prize”.16 She notes that the prize, which began in 1979, had no women on the jury until 1987 and that since 2005 there have been only three women jurors. She cites research that demonstrates a consistent bias in assessment panels towards reproducing the majority culture. In other words, if men comprise a larger proportion of panel members, the panel replicates this dominant group in their selection. Her research also clearly demonstrates that, if those awarded the Pritzker Prize are deemed the most successful designers in the profession, this model favours the masculine. This further substantiates the research by Mendelberg and Karpowitz cited above.

I’d like to mention Hilde Heyen’s critical analysis of the Pritzker Architectural Prize. Her essay “Genius, Gender and Architecture: The Star System as Exemplified in the Pritzker Prize” explores the “sexist bias in awarding the prize”.16 She notes that the prize, which began in 1979, had no women on the jury until 1987 and that since 2005 there have been only three women jurors. She cites research that demonstrates a consistent bias in assessment panels towards reproducing the majority culture. In other words, if men comprise a larger proportion of panel members, the panel replicates this dominant group in their selection. Her research also clearly demonstrates that, if those awarded the Pritzker Prize are deemed the most successful designers in the profession, this model favours the masculine. This further substantiates the research by Mendelberg and Karpowitz cited above.

I would also like to highlight the petition by two former female graduate students at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design seeking recognition for Denise Scott Brown and her partnership and collaboration with Robert Venturi and his 1991 Pritzker Prize award. One could argue that Denise Scott Brown is one of the few matriarchs of twentieth-century architecture – and one of the only women I remember learning about as an undergraduate architecture student. Although the petition received over 19,000 signatures and generated much publicity, the Pritzker Prize Committee did not grant the petition’s request.

Women and Work – Having it all

Jumping to summer 2012, I want to briefly discuss Anne-Marie Slaughter’s widely read article in the July/August issue of The Atlantic “Why Women Still Can’t have it All.” 17

This precipitated an avalanche in both print and online journalism. Slaughter is the former first woman director of policy planning at the State Department under former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton (2009–2011), former dean of Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of International Relations, Professor Emerita of Politics and International Affairs at Princeton University, and currently the President and CEO of the New America Foundation, a public policy institute. Her article stems from her personal experience of juggling an incredibly successful career in academia and government and the immense personal difficulties she experienced while at the State Department when issues arose with one of her teenage sons at home. She explains her motivations in writing the article as follows: “when many members of the younger generation have stopped listening, on the grounds that glibly repeating ‘you can have it all’ is simply airbrushing reality, it is time to talk.” She continues, “I still strongly believe that women can “have it all”…” But not today, not with the way America’s economy and society are currently structured. [My] experiences over the past three years … forced [me] to confront a number of uncomfortable facts that need to be widely acknowledged – and quickly changed.”

Slaughter quotes Kerry Rubin and Lia Macko, authors of Midlife Crisis at 30. Their research found that “…while the empowerment part of the equation has been loudly celebrated, there has been very little honest discussions among women of our age about the real barriers and flaws that still exist in the system despite the opportunities we inherited.” I heard similar sentiments during the Van Alen roundtable discussions I led for my book Feminist Practices.

Slaughter argues that “The best hope for improving the lot of all women, and for closing … a “new gender gap” – measured by well-being rather than wages – is to close the leadership gap: to elect a woman president and 50 women senators; to ensure that women are equally represented in the ranks of corporate executives and judicial leaders. Only when women wield power in sufficient numbers will we create a society that genuinely works for all.” Slaughter argues that several key factors must change before we can achieve better balance. These include:

1. Changing the culture of face time.

We in architecture can clearly relate to this. “The culture of “time macho” – a relentless competition to work harder, stay later, pull more all-nighters, travel around the world and bill the extra hours that the international date line affords – remains astonishingly prevalent among professionals today.”18

As Slaughter writes, in professions where total hours spent on the job are not “explicitly reward[ed]” the expectation “to arrive early, stay late, and be available, always”, even on weekends can exert great pressure. This is something architects can identify with. Possibilities for change include redefining not only the time but place of work – working from home and employing technologies that enable telecommuting provide different options for how we manage work and personal time.

2. Redefining the arc of a successful career.

To this I would add redefining what a ‘successful’ career looks like – specifically within the discipline of architecture.

Slaughter writes, “[t]he American definition of a successful professional is someone who can climb the ladder the furthest in the shortest time, generally peaking between ages 45 and 55. It is a definition well suited to the mid-20th century, an era when people had kids in their 20s, stayed in one job, retired at 67, and were dead, on average, by age 71.”

She provides a positive example in the tenure-track process within academia, which demonstrates how an institution can create policies that support all faculty.

“[I]n 1970, Princeton established a tenure-extension policy that allowed female assistant professors expecting a child to request a one-year extension on their tenure clocks. This policy was later extended to men, and broadened to include adoptions. In the early 2000s, two reports … discovered that only about 3 percent of assistant professors requested tenure extensions in a given year… [a]nd women were much more likely than men to think that a tenure extension would be detrimental to an assistant professor’s career. [I]n 2005, under President Shirley Tilghman, Princeton changed the default rule … announc[ing] … all assistant professors, female and male, who had a new child would automatically receive a one-year extension…with no opt-outs allowed. Instead, assistant professors could request early consideration for tenure if they wished. The number of assistant professors who receive a tenure extension has tripled since th[is] change.”

3. Innovation nation

Slaughter mentions Deborah Epstein, a former big-firm litigator and now president of Flex-Time Lawyers, a national consulting firm focusing on strategies for the retention of female attorneys. In Law and Reorder, Epstein argues:

“… a legal profession “where the billable hour no longer works”; where attorneys, judges, recruiters, and academics all agree that this system of compensation has perverted the industry, leading to brutal work hours, massive inefficiency, and highly inflated costs. The answer – already being deployed in different corners of the industry – is a combination of alternative fee structures, virtual firms, women-owned firms, and the outsourcing of discrete legal jobs to other jurisdictions. Women, and Generation X and Y lawyers more generally, are pushing for these changes on the supply side; clients determined to reduce legal fees and increase flexible service are pulling on the demand side. Slowly, change is happening.”

It is important to note that, thus far, both law and medicine have been far more successful than architecture in retaining and promoting women into their upper ranks. Clearly this rethinking of law’s professional structure will create even more positive changes to the practice of Law. We have much to learn from their successes.

Slaughter concludes her essay by writing that, “[i]f women are ever to achieve real equality as leaders, then we have to stop accepting male behaviour and male choices as the default and the ideal. We must insist on changing social policies and bending career tracks to accommodate our choices, too… We’ll create a better society in the process….”

There is much to learn from the article, but it does not accurately reflect the generations – both men and women – younger than her. Slaughter acknowledges her position of privilege (including a tenured husband also teaching at Princeton), but does not discuss are all those that fall outside this elite world: single people, the working poor and middle-class families struggling to make ends meet. These groups have very little power to demand such things as flex-time, equal pay or even paid sick leave and are often just thankful to be employed.

Rethinking architectural work

Slaughter’s article also helped me to recognise the generalised acceptance of architecture’s professional and hierarchical structure. We have not yet called out for radical rethinking of how work works. Some readers may be familiar with the fascinating study by the sociologists Bridget Fowler and Fiona Wilson, which examines architecture as a “typical masculine-dominated profession”. They aim to “clarify the material and cultural constraints that block the path to gender progress. It is only by grasping the social relations on which women’s participation is premised that equal access to the fields of modern professional performance can be granted.”19 The authors develop “an explanation of the deep-rooted gender inequalities within architecture in terms of a ‘naturalized social construction’ of masculine domination.” I would like to highlight two points from this research that have the potential to impact on our thinking of how architecture work works.

The first centres on our educational system and the indoctrination of young students into “becoming an architect”. One of these “rites of institution” is the studio system. The “masters” are male and design juries, typically, have few women reviewers among a coterie of men.20 As Fowler and Wilson state, “design education is structured through an individualistic masculine culture somewhat like a boot camp dominated by competitions, star system, and high-risk gambles.”

My second point relates Fowler and Wilson’s conclusion. They write:

“the profession may be rationalised to allow women’s entry while permitting men merely to regroup to retain their collective interests linking this to not only allow men to shine among other men but also to the nature of renewed market structures and their new ‘spirit of capitalism’ While liberating architectural ‘stars’ from parochial boundaries and deploying a rhetoric of flexibility or authenticity which might appear to favour women, harsh economic climate has in fact undercut the conditions which are conducive to gender equality.21

In essence, we are not getting anywhere near gender parity quickly.

Women and Work – Leaning in

The other recently popularised and politicised book I want to discuss is Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In published in 2013. Sandberg, Google’s Chief Executive Officer, cites statistics to illustrate the global scope of gender disparity. Women are not making it to the top of any profession any where in the world.

Of 190 heads of state in governments worldwide, only 9 are women. Only 13% of all the parliaments are women. In corporate sector c-level jobs and board seats worldwide, there are approximately 15 –16% women. These statistics have remained the same since 2002 and are currently declining. Even in the non-profit world (generally considered to be more women friendly) only 20% of the leaders are women.22 And in academia in the United States, only 24% women are full professors. Women are nowhere close to 50% representation on decision-making bodies – this means we do not have an equal voice at the table. Sandberg believes that we will only start to solve this generation’s moral problem of gender equality when gender equality exists across governments, businesses and universities. She argues there must be more women at all levels in order to change and reshape the conversation. This is the only way to make sure women’s voices are heard and heeded, not overlooked and ignored. She also states that her generation is not going to change this problem. Thirty years ago women became 50% of college graduates – which should have been enough time for change to occur – but it has not.23

Like Slaughter, her basic argument can be distilled into 3 larger ideas.

1. Sit at the table

Sandberg argues that women systematically underestimate their own abilities. Women do not negotiate in the workforce. For her this matters because “no one gets to the corner office by sitting on the side, not at the table. No one receives the promotion if they do not think they deserve their success or they do not understand their own success.”24

2. Make your partner a real partner

There has been more progress towards gender parity in the workforce than in the home – data clearly demonstrates this. Studies show households with equal earning and equal responsibility have half the divorce rate. Being in a relationship with greater equality proves to be beneficial not only for the couple and their family but also for society at large.

3. Don’t leave before you leave

She believes actions women are taking with the intention of staying in the workforce actually leads to their eventual departure. Sandberg provides an example where the moment a woman begins to consider having a child. To make room for that child she begins to leave in incremental ways. The concern of “how I am going to fit a child in with everything else I am doing” can begin to establish a different professional path. Sandberg says a woman raises her hand much less and she starts leaning back. She doesn’t ask for the promotion, she doesn’t take on the new project, and she doesn’t say “I want to do that!”

In Part 2 of this essay Lori Brown explores how we might draw on initiatives from other fields to help change our own discipline. She found many inspiring groups making significant and far reaching changes in professions still lacking gender parity. These creative strategies include both bottom up and top down approaches that architecture can learn from.

- “Facts, Figures, and the Profession,” The American Institute of Architects. Arlene Hirst, “Women in Design: Confronting the Glass Ceiling,” accessed April 27, 2013. The American Institute of Architects counted 83,000 members at the end of 2012, yet only 18 percent are women. In contrast, according to Interior Design’s recent Universe Study, of the 87,000 interior designers in the United States, a whopping 69 percent are women.[↩]

- Alison Rourke, “Julia Gillard’s attack on sexism hailed as turning point for Australian women,” The Guardian, accessed May 22, 2013.[↩]

- Robert Pear, “Obama Reaffirms Insurers Must Cover Contraception,” New York Times, January 20, 2012, accessed March 14, 2012.[↩]

- Laura Bassett, “Obama Birth Control Compromise Announced (UPDATE)”, Huffington Post, February 10, 2012, accessed May 16, 2012.[↩]

- Robert Pear, “Passions Flare as House Debates Birth Control Rule,” New York Times, February 17, 2012, accessed May 16, 2012.[↩]

- Jen Doll, “Why Are Men Dominating the Debate About Birth Control for Women?” The Atlanta Wire, February 16, 2012, accessed May 16, 2012.[↩][↩]

- J. Lester Feder, “Carolyn Maloney, Eleanor Holmes Norton walk out of contraception hearing,” Politico Pro, February 16, 2012, accessed May 16, 2012.[↩]

- Center for American Women and Politics, “Women in the U.S. Congress 2013 Fact Sheet.” April 2013.[↩]

- Jennifer Steinhauer, “In the House, a Step Toward Potty Parity,” New York Times July 20, 2011, accessed April 30, 2013. See also Amanda Terkel and Ryan Grim, “How A Women’s Bathroom Helped John Boehner Pull Off A Capitol Land Grab,” Huffington Post February 4, 2011, accessed April 30, 2013. In the Senate chamber, a woman’s restroom was constructed in 1993 when female senator numbers increased from four to seven.[↩]

- “2011 Report on Accreditation in Architecture Education,” The National Architectural Accrediting Board, Inc. (March 2012), 28-30.[↩]

- “Academic Leaders in Architecture,” accessed March 21, 2013.[↩]

- Despina Stratigakos, “Why Architects Need Feminism”, Places, 2012[↩]

- Tali Menderberg and Christopher F. Karpowitz, “More Women, but Not Nearly Enough.” New York Times The Opinion Pages November 8, 2012, accessed April 28, 2013.[↩]

- Menderberg and Karpowitz 2012.[↩]

- Linda Babcock and Sara Laschever, Women Don’t Ask Negotiation and the Gender Divide (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), xiii.[↩]

- Hilde Heynen, “Genius, Gender and Architecture: The Star System as Exemplified in the Pritzker Prize” Architectural Theory Review 17(2-3) 2012, 332.[↩]

- Anne-Marie Slaughter, “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All,” The Atlantic July/August 2012, accessed October 6, 2012.[↩]

- Kate Bolick, “Single People Deserve Work-Life Balance, Too,” The Atlantic June 28, 2012, accessed October 6, 2012.[↩]

- Bridget Fowler and Fiona Wilson, “Women Architects and Their Discontents,” Sociology 38(1): 2004, 102.[↩]

- See also Lori Brown and Joseph Godlewski, “7 Ways to Transform Studio Culture & Bring It into the 21st Century” 13 Jun 2014, ArchDaily.[↩]

- Fowler and Wilson 2004, 117.[↩]

- The book is based on Sandberg’s earlier “Why we have too few women leaders,” TED Women’s talk December 2010.[↩]

- Sheryl Sandberg, Barnard College 199th Commencement Ceremony speech.[↩]

- Sheryl Sandberg, “Why we have too few women leaders”.[↩]