Jim Gall discusses traditional architectural perspectives of sustainability, and the need for architects to re-think design to ensure a more sustainable future.

An overarching problem for now and the future is the design and making of human habitation that can sustain and be sustained by the ecosystems that support it. This makes sense as the way humans can continue to inhabit the Earth.

However, this forms a definition of sustainability that is well beyond the one understood by architects and the construction and development industries. It’s the same understanding of sustainability embedded in my early environmental/ecological education and one that is not new. It wasn’t until architects began talking about regeneration as the next step on from sustainability that it became apparent that their definition of sustainability was limited to the application of technologies and practices to the construction and use of buildings to reduce their biophysical (related energy, materials, water, waste, etc.) impacts. The assumption of building is not questioned – perhaps not even seen. This only allows the inherently unsustainable to be sustained for a while.1 Sustainability is not a technological/practical problem. It is a social/cultural problem. It is a people problem.

The idea of regeneration is embedded in this broader understanding of sustainability.

A seemingly new concept to architecture/architects, it’s been seen and understood for a long time (see, for example, G. Tyler Miller’s book Living in the Environment (1974), which talks at length about carbon dioxide emissions and global warming). Certainly, the idea of repair and design/making of systems that regenerate and/or reinstate sustainable and sustaining ecological systems (not limited to the biophysical) has been championed, studied and implemented by ecologists, biologists and a whole bunch of others usually consciously, and sometime unconsciously.

Architecture should lift its eyes from buildings as just technical, material objects. The designing of regenerative buildings or other commodities is something of an illusion. To design and make (build, in our case) requires destruction. Embodied (if you will) impacts on a vast range of systems ”upstream“ of the building, in construction and ongoing during use and occupation of land, space and time. At a foundational level, it is not possible to create without destroying. If you contemplate relationally, understanding that the environment is everything, not just the biophysical, and reach back though the destruction that occurs before and around a building through time, you realise that a new building can’t regenerate more than it destroys. A “normal” architectural project can never be regenerative.

This doesn’t mean architecture/architects have nothing to do or cannot work on regenerative projects. It means design as a way of thinking has to be much better understood. As Tony Fry and others say, it may be that it is used to eliminate something (elimination design) or the need for something.2

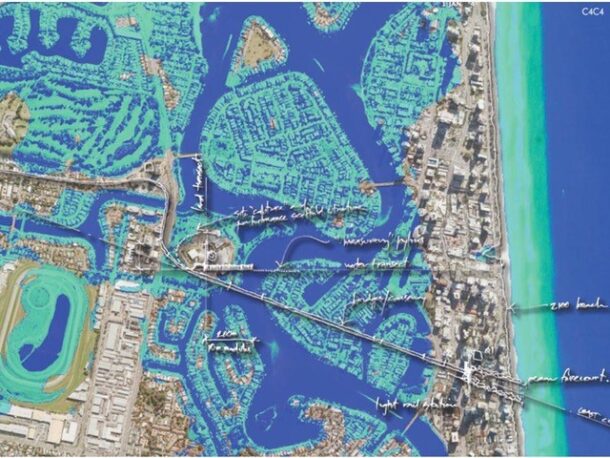

The Gold Coast 2100 probable scenario: sea level rise with storm surge and flooding. (Image courtesy of Jim Gall from an ideas competition winning entry by Team DES, Gall & Medek Architects and staff and students of Design Futures at the Queensland College of Art, Griffith University, 2007).

The opportunity is for design to have a much broader scope than new buildings. Designing should be involved before defining any action(s). These opportunities are lost if design isn’t in place at the beginning to question, re-imagine and develop a brief.

What this means or at least suggests, is that design outcomes must be considered broadly beyond the material/physical/built. They might move us (head and hearts) from the material to the immaterial, from the quantitative to the qualitative. They might be managerial. They might be social. They might be experiential. Or they might be virtual. They can be regenerative rather than destructive.

Through design, as part of brief development, the need for something may be eliminated. Increasingly into the future, the outcome may not even be built.

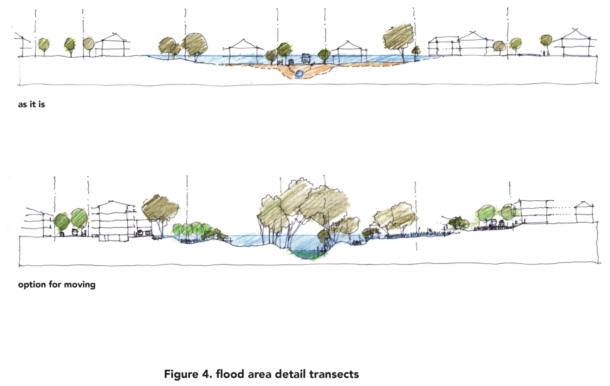

How can people living in flooding areas be moved out of harm’s way as the frequency and volume of flooding increase? (Image courtesy of Jim Gall, 2022)

This article was originally published on the Better Briefing for Design website and has been republished here with permission.

Jim Gall is the Director of Gall Architects and design educator at Queensland University of Technology (QUT) in Brisbane, Australia. Jim’s first degree is in Environmental Science, hence his multi-disciplinary and ecological view of the world. He is especially concerned with the importance of design as a way of thinking and acting and the enormous opportunities and possibilities sustainability offers for architecture to have a core role in working with the complexities of making our place in a complex world.