One of the standard ways to measure women’s participation in architecture is to look at the numbers of registered architects. But this is no straightforward matter in Australia. Gill Matthewson describes the trials and tribulations of counting registered women, and finishes the most accurate count we have to date.

If we want to work out what might be happening to women in architecture, then counting them is a good start – and counting registered architects in Australia should be an easy matter. I have been monitoring the count in New Zealand for a number of years; it takes less than half an hour to check this.

Australia is a larger country, so I expected the process here to be a bit trickier – but not nearly as tricky as it has turned out to be. The main issue is that Australia has more than one register. Architects are registered according to the Architects Act, legislated in each state and territory. Each state register is separately maintained and statistics for each state are held in different ways. In addition, to be the signing architect in a state, you must be registered there as well as in your home state. As a result many architects are registered in more than one state, and this is particularly common for architects that practice close to a state border.

Previous attempts to remedy this distortion of the figures involved extracting those architects not resident in a state from the count. We realised however, that a significant number of people are registered in one state (perhaps the state in which they first obtained a job) but are resident and working in another. These people are not registered in the state they currently work within, because they are not doing any of the legal sign-off of projects. So, this attempt to account for double-ups in registrations resulted in other inaccuracies.

In September 2012 the Architects Accreditation Council Of Australia (AACA) published a combined register for Australia, from information provided from each independent state board. This information was collated in alphabetical order, which meant that those registered in more than one state could be easily identified. This was a breakthrough. The combined register of over 12,500 entries was still, however, not entirely accurate – it was only as good as the information provided by each state. Non-practising architects in Western Australia and Victoria were included, along with companies registered in South Australia and a handful of people from the Australian Capital Territory were listed more than once. Some people were also recorded as located overseas.

To count registered architects all these anomalies — 10% of the entries — had to be removed from the calculation. The WA and VIC registers also had to be crosschecked for non-practising or inactive architects. Once the anomalies were isolated, each name had to be examined to determine gender. This determination was initially based on the gender commonly attached to the Christian name given, and the majority of names could be linked to a particular gender through this means. Less common or ambiguous names are currently being crosschecked in a number of different ways, including through:

- Googling the full name to see if a digital presence for the person exists, on Facebook, LinkedIn, etc. Photographs or other information online can potentially indicate gender.

- Crosschecking people who are registered in Queensland against the names on the Board of Architects of Queensland website, where they are listed with a gender title such as Mr or Ms (thank you Queensland).

- Checking names against websites that give the probability of a name by gender (although the results from this kind of search can be varied, particularly between different countries. ‘Ashley’, for example, is more commonly a female name in the USA and more commonly a male name in Australia).

Names in Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese and other East Asian languages posed some of the biggest challenges, as it is often not possible to determine the gender of name without seeing that name written in Chinese characters. For now, these names have been randomly assigned a gender, until further checking can be done.

The trend for females to be named with traditionally male names and spellings (and occasionally vice versa) also created some difficulty. In these cases, sometimes a listed second name clarified gender, but otherwise it was largely undetectable.

As each name on the register was checked for gender, where the address and name indicated a multiple state registrant, it was possible for the first time to count that registrant only once. Of all the entries in the full register, 1425 or 11% are multiple registrations. And men are more likely to be a multiple state registrant than women (1310 men and 115 (or 8%) women).

The information from the AACA included the state in which a person was registered, allowing a formula to be developed (with a great deal of head-scratching) to automatically count a person in their state, once they were established as an individual legitimate entry through the gender-checking process.

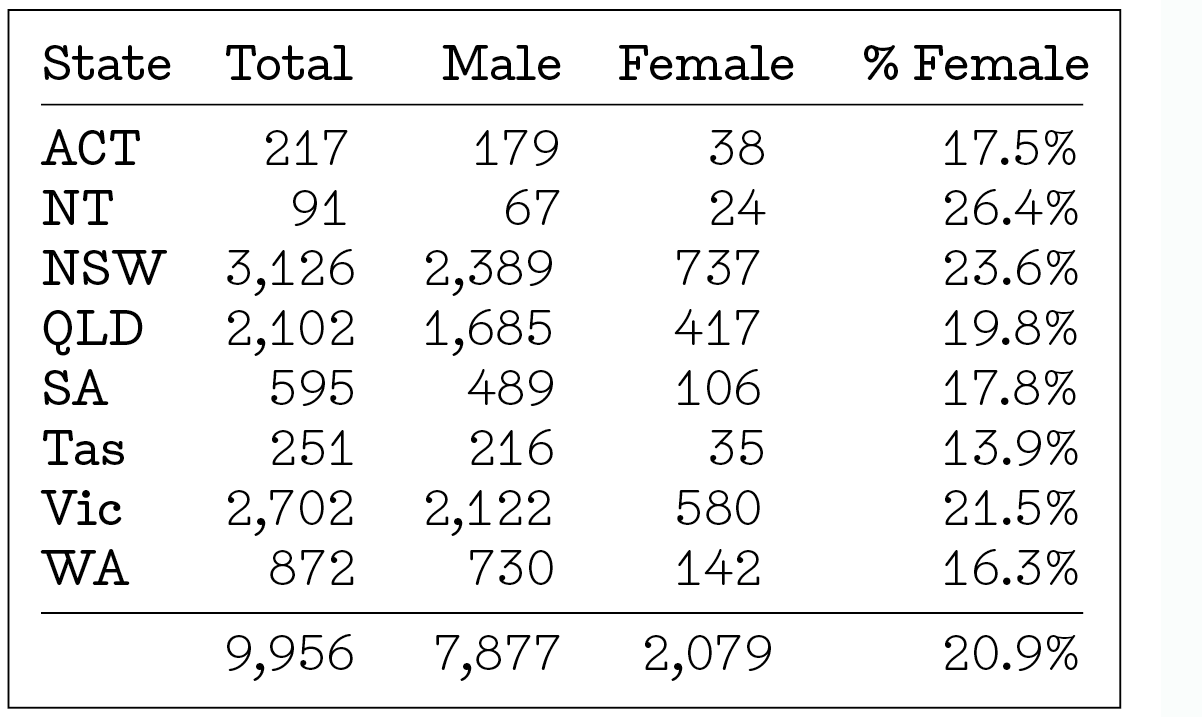

All the gender ‘assignments’ still need double-checking, but for the moment the numbers stand as follows:

One day we hope the register will be cleaner and easier to count. One day.

2 comments

Enamored With Place says:

Jan 17, 2013

Good work Gill,

Admirable effort to learn the sex of registered Australian architects. In the USA, each of the 50 state collect their own data, and about two years ago, when I asked New York State, one with lots of architects, they said that they didn’t identify the sex of registered architects (or any other social asset like race, disability, or marital status, etc). So what is often used in USA statistics is the numbers from the American Institute of Architects (AIA), however this institution can not claim that they speak for all licensed architects and I don’t know if they are are careful as you were in collecting your data. Bravo.

gill says:

Jan 17, 2013

Ah, that’s interesting to know. Thanks.

I think the information isn’t collected because people subscribe to the idea that such things make no difference – an architect is an architect. I would so like that to be true too, but unfortunately it simply isn’t. Architects reflect society and all its attendant inequities based on gender, race, economic and family background, etc. And by not collating that data they hide the issue.