In the midst of many tributes to Zaha Hadid, Gill Matthewson offers a short reflection on what her career means in the context of gender and architecture, while John Gollings shares a fabulous image from his archive.

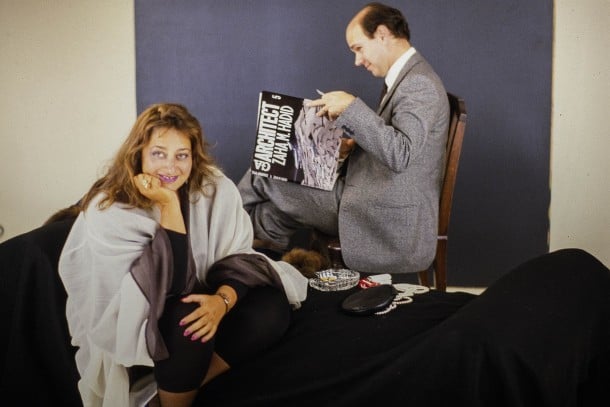

Zaha Hadid with Ian McDougall, Melbourne. Photograph by John Gollings, who explains “It was a relaxed family sort of visit, kids all around talking to her. She agreed to some group portraits. Her book of renderings had just come out, which is what Ian is looking at. Note the Marlboro ciggies which she chain smoked in those days.”

Zaha Hadid has died suddenly in Miami at the young age of 65. She has been a controversial figure in architecture. For some, she was an inspirational and visionary architect who broke rules and showed us the possibilities of an ambitious and complex architecture of new experiences; an architecture of the future and way outside the norms. For others she was the epitome of the self-absorbed, arrogant architect.

I see her as someone who demonstrated just how much determination and social, cultural, economic (and, perhaps, exotic) capital a woman of her generation needed to break through the enormous barriers her gender raised in the world of architecture.

As John Seabrook wrote in the New Yorker following her death, “she took no shit from anybody, though plenty was offered.” That the plentiful shit she received was liberally laced with sexism is undeniable1, but her presence has helped reduce that sexism for subsequent generations. It’s still there, but less.

Rem Koolhaas once called Hadid ‘a planet in her own inimitable orbit’. Some might argue that that orbit had become more predictable in recent years, but she showed that there are potentials for other orbits to exist in architecture. We should honour and celebrate that.

Footnote

- Igea Troiani (2012): Zaha: An Image of “The Woman Architect”, Architectural Theory Review, 17:2–3, 346–364.[↩]