Nothing to see here – Janina Gosseye reflects on her recent experience of being written out of history and the challenge of how to respond, and longs for a time when such considerations are no longer necessary.

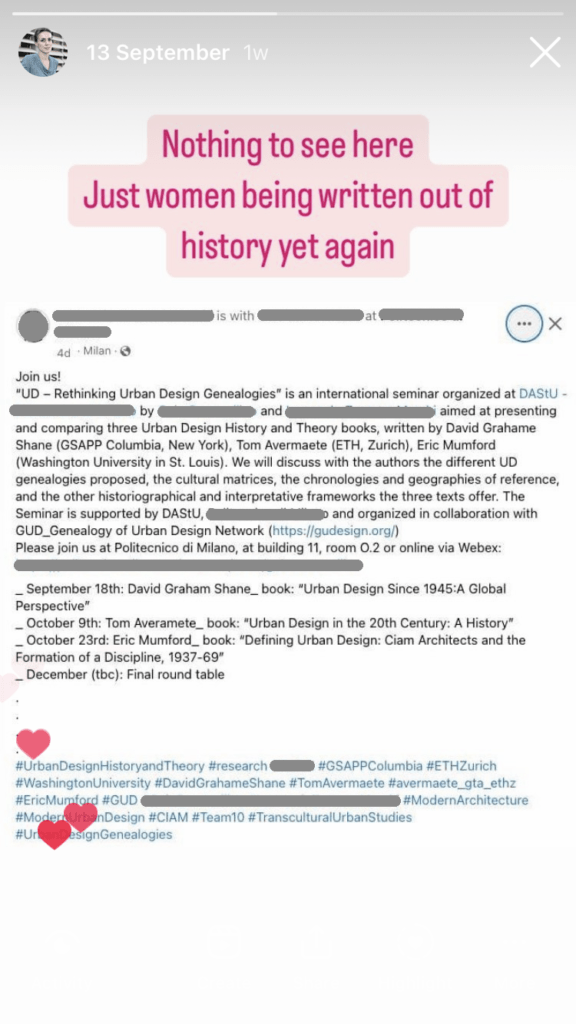

One morning in mid-September 2023, I read a post on Facebook that started with “Join us!”. It was about an event taking place at a respected European university the following month, entitled Rethinking Urban Design Genealogies. This “international seminar” – so the author of the post, who was also one of the two organisers of the event, wrote – “aimed at presenting and comparing three Urban Design History and Theory books, written by David Graham Shane (GSAPP Columbia, New York), Tom Avermaete (ETH, Zurich), [and] Eric Mumford (Washington University in St. Louis).” The post continued: “We will discuss with the authors the different UD [urban design] genealogies proposed, the cultural matrices, the chronologies and geographies of reference, and the other historiographical and interpretative frameworks the three texts offer”. At the bottom of the post and in the accompanying event poster, which was shared along with it, the titles and authors of the three books were mentioned: Urban Design Since 1945: A Global Perspective by David Graham Shane, Defining Urban Design: CIAM Architects and the Formation of a Discipline, 1937-69 by Eric Mumford, and Urban Design in the 20th Century: A History by Tom Avermaete and myself. Except, even though the title of our book and Tom’s name were mentioned, my name was nowhere to be seen. It did not show up in the Facebook post, or on the poster. I, a historian, had been carefully excised from the history of historiography. Ironic, I thought. But then again “well behaved women rarely make history”, right?

Upon seeing the post and poster, my blood began to boil. I called two close friends, both women, both academics. I ranted. I told them: “I am going to make a fuss about this” and “I am going to post on social media”. Both friends, who I respect and admire greatly, prompted me to sit on it for a little while; think first and then act. “Wait until the evening” and “think carefully about how to respond”, I was told. This is the advice I would have likely given them as well, had they called me with a similar predicament. I too would have said: “let it sink in” and “think about the consequences”. And so, reluctantly, I heeded their advice and did just that… for about half an hour.

Whenever my stress levels get high – too high – my body responds: my left eyelid starts twitching and the drum in my right ear starts vibrating intermittently for no apparent reason. In the thirty minutes that I waited, to let it sink in, the left eyelid began to twitch. I knew that the vibrating eardrum was not far off. I could not focus on anything – certainly not on the important deadline that I had by the end of that day. All I could think about was the Facebook post and the event poster. I felt hurt, angry, sad. I knew that until I responded in some way, I would be stuck thinking about it. Then the thought occurred: why should I spend hours of my day reflecting carefully on how to formulate a measured response, when such careful consideration – such respect not only for the work, but also for the feelings of others – had clearly not gone into preparing this event?

About an hour after reading the Facebook post, I created my own, sarcastically congratulating the organisers of the seminar for putting together an all-male line-up, and scathingly stating: “If only I, a young woman academic, could write such a book”. I accompanied this post with an image of the cover of the book that Tom and I had written, which (evidently) mentions both our names. Then I went on to Instagram, where I created a story along similar lines, which made it even more plain that I had been deliberately left out: not only had I not been invited to speak, but the organisers had also chosen not to mention my name in their advertising as an author of one of these ‘urban design genealogies’ that they planned to discuss.

I received many messages that day. Tom, with whom I wrote the book, was quick to jump to action. Surprised and dismayed by the announcement (which he had not seen previously), he immediately wrote to the organisers, first demanding that they add my name to the poster, then suggesting that I take his place in the seminar. Apart from Tom, others responded as well. About 120 people reached out to me, both men and women, some of whom I know well, others less so. Their responses can be largely grouped into three categories.

First, there were messages of support and encouragement. People shared the post on their own social media accounts, sent facepalm emojis and raised fist emojis accompanied by the words “in solidarity”; they encouraged me to “say it loud” and “set them straight”. The second category of responses can be grouped under the term ‘anger’. The words ‘frustrating’, ‘infuriating’, ‘unacceptable’ and ‘sexist’ came up quite a bit, as did the expression ‘FFS’.

The third and final category were responses of sadness, surprise, and exasperation. Students and younger colleagues were dumbfounded that I, a ‘senior academic’ could have been excluded so blatantly, so unapologetically. “Didn’t know all male panels were still a thing” and “I thought that these days were over”, people wrote. Two young PhD students of mine (independently of each other) wrote that they were saddened to see that such a thing could still occur. Reading their messages, my heart sank. I thought that I was squashing people’s hopes for (or ideal of) an inclusive and equitable academic environment. Then a woman I met at a conference a decade ago wrote “This is one of the reasons I left academia”, and another friend, who recently obtained her degree in architecture, asked if she could share the post, explaining that “Many of my friends are young professionals who already feel the struggle. Me included.” Their responses shook me. I realised that I was, in fact, not squashing anyone’s hopes or ideals, but merely addressing something that many working and studying in academia still face every day: exclusion based on gender, skin colour, age, sexual orientation, religion, etc. Such exclusions and slights are often not as visible as the one that I experienced that day. They are more insidious, and therefore more difficult to call out in the very public way that I did – even more so for those in less privileged academic positions than myself.

Although I was (and am) immensely grateful for all the messages and support that I received that day as well as the following days, the thought kept nagging at me: Did I do the right thing? Should I have refrained from going public and dealt with this in a more private manner (as the organisers suggested I should have done when they saw my social media posts). Admittedly, it was not my finest hour. My reaction was visceral. I snapped. All I could think about was that I wanted ‘a pound of flesh’, and so I consciously engaged in publicly shaming two colleagues (the organisers of the event, both of whom are about my age). It was not a diplomatic response, nor a very collegial one, but it was honest and unfiltered.

Isabelle Doucet, with whom I discussed these after-the-fact ruminations, referred me to Sara Ahmed’s book Living a Feminist Life. In this book Ahmed writes about ‘the feminist snap’: a moment in which you realise that you can no longer carry on just doing what you are doing; a moment when you realise that it has become too much to bear. Another colleague, with whom I shared this text prior to publication, similarly reminded me that my ‘snap’ did not come out of the blue. It was the result of working in academia – with all its explicit and implicit power relations – for nearly two decades. Historically speaking, this environment has been just as exclusive as the historiographies that it has produced. In this sense, the organisers of the seminar were right: there is a lot of ‘rethinking’ to do. I would, however, argue that this rethinking should not be limited to the historiographies that we record, but should extend to those recording them. The genealogies of academia need to change.

Returning to my main question: to post or not to post. I am still unsure whether I should have gone public with this ordeal on social media or not. I also do not know whether I would do it again in the future – one friend remarked that “there is always damage”. What I do know, is that I long for a future where such ponderings – along with the need to call out bias and discrimination in whatever shape or form – have become obsolete.

Janina Gosseye is Professor of Building Ideologies in the Department of Architecture, Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment. Her research is situated at the nexus of 20th century architectural and urban history on the one hand, and social and political history on the other.

Janina has previously held academic positions in Belgium, Australia and Switzerland. She is currently series editor of the ‘Bloomsbury Studies in Modern Architecture’ book series (with Tom Avermaete), a member of the European Science Foundation College of Expert Reviewers, Honorary Senior Fellow at the University of Queensland, and Honorary Member of the Australian Institute of Architects.