Jen Rodezno had been designing inclusive seniors’ communities, hospitals and schools for decades when her gloriously independent and social mum Joyce Tepper developed dementia, had a series of falls, and entered aged care as Covid struck. For Jen, personal experience underscored the power of design to help communities move beyond ageist assumptions and prioritise social connection and multi-generational interdependence.

Living means ageing. We’ve all been at it since birth. So, why have we internalised so many negative stereotypes about older age, especially when we’re surrounded by so many positive role models? Is it personal experience, fear or cultural cliches shaping our unconscious biases about older people as dependent, frail, a burden to be managed? We’d never reduce our own abilities, interests or value to match a number on a birth certificate. But we’re conditioned to understand older age as a lessening: of productivity, outlook and agency. We’re pretty loose about who we label, too, often lumping anyone from 60 to 90 into the same ‘old’ basket – until we approach it ourselves.

These ideas can become self-fulfilling prophesies. At a panel discussion my practice ClarkeHopkinsClarke Architects hosted in September 2022 about designing to defy ageism, Professor Pazit Levinger, principal researcher and exercise physiologist at NARI (National Ageing Research Institute), talked about how some older people internalise these limiting beliefs and avoid activities like outdoor exercise programs tailored to their needs. Evidence shows that these programs actually help them stay healthier, happier and socially connected for longer. Study after study highlights the adverse effects of ageist beliefs on our physical and cognitive health, wellbeing and sense of belonging. This is associated with increased social exclusion, diminished relationships and social roles, and greater loneliness, particularly for those with limited mobility, means or networks (after the loss of a spouse, especially). Seniors who stay socially engaged, not surprisingly, report much higher rates of happiness.

Professional inevitably becomes personal

My late mum Joyce’s recent experiences in care reflect all this to a tee. Like so many people forced into aged care by dementia and falls, Mum had been independent and sociable her whole life. A single parent and a customer service person who always loved a chat, she thrived in the sociable environment of a retirement village, and met the love of her life at age 78. But by the time she was forced into aged care during Melbourne’s long pandemic lockdown, social engagement had stopped in its tracks for Melburnians. She wasn’t able to tour facilities or decide for herself which might suit her best. So her partner, my sister and I had to try to anticipate her changing needs and preferences.

I’ve worked in seniors and dementia design for much of my career, in a practice that masterplans and designs facilities for maximum social engagement and community connection, and even for me this process was confronting and often counter-intuitive. For example, we found a lovely facility but chose a room in a quiet wing for Mum because she had great hearing and often found hospitals too noisy for a good night’s sleep. Over time, she became socially isolated and withdrawn. Ironically, when she contracted Covid she bounced back socially because she was forced to isolate near the busy nurses’ station, where the constant activity and chats with staff about their lives and daily happenings restored her to her sociable best. As soon as she recovered physically and moved back to her quiet space, she relapsed socially.

For me this was a valuable reminder that as designers, although we’re guided by stakeholder engagement at key moments in the design process, we’re also constantly making decisions on others’ behalf. Truly understanding their changing needs and preferences means talking more regularly with more diverse residents, families and staff to better understand their daily lives, and co-designing spaces where autonomy and multi-generational relationships can thrive.

Co-designing for multi-generational connection

Co-design is a growing focus for our practice and clients. When we listen deeply and design collaboratively with a wide range of residents, staff, families, community stakeholders and seniors’ advocacy organisations like Dementia Australia, we can defy ageist stereotypes and create welcoming, non-institutional environments that connect residents with their interests and networks, nature and neighbourhood. Design drivers open up accordingly: connection to home, site and Country. Detailing inspired by local contexts and narratives. Fresh approaches to form, colour, materiality and scale. At Rutherglen in north-eastern Victoria we’re involved in an innovative project achieving much of this through several key strategies.

For years, residents in and around Rutherglen in Victoria’s north-east have been forced to move away from their families and support networks to access residential aged care and many allied health services. Rutherglen Aged Care is a new community our practice has co-designed with client the Victorian Health Building Authority and an exceptionally broad mix of residents, family, staff, other community members and advocacy organisations including Dementia Australia. Construction starts later this year and, when completed, this facility will deliver small household care for 50 residents and intergenerational community facilities for the whole of Rutherglen. It introduces new allied health services and a healthy mix of indoor and outdoor environments that are dementia-friendly and universally accessible – all shaped by evidence-based research and contemporary models of care focused on resident and staff wellbeing.

A broad mix of stakeholder workshops was central to the process. Our architects designed and delivered a series of workshops that welcome participants into the ideation process as equal partners, helping us drill down into the minutiae of residents’ lived experiences, understand stakeholders’ needs, challenges and preferences, and design spaces that support them. The following were some of the most useful activities and strategies:

Journey mapping

We used informal conversations with residents to understand their life journeys before and after moving into care. I saw journey mapping deployed successfully at Mum’s aged care facility, too. Staff created visual maps on the wall of residents’ rooms using photos supplied by family members to show key aspects of their lives, their family tree, and personal likes and dislikes. It‘s such a simple strategy, but it really helped staff relate more personally to residents, which prompted my mum to open up in return and form closer relationships with staff.

A day in the life discussions

Discussing residents’ daily routines, rituals and preferences around everything from bathing to preparing food is invaluable for designers but also for staff in creating time and spaces that support residents keen to do many tasks in their own time and way. Mum’s experience as a lifelong night owl, forced by her facility’s timetable to wake and go to bed much earlier than suited her, have attuned me to seeking out every little opportunity to support residents’ agency.

Ideas workshops and briefing packs

We invited ideas from all residents who wanted to have input into the design, and prepared them with briefing packs including a storyboard of key spaces and an accessible explanation of design development to date.

Cognitive decline group activities

Guided by expert advice, in workshops with residents living with cognitive decline, we focus less on verbal discussions and more on tasks and activities to capture their views and input.

Participatory working group sessions

When the time came for more detailed sessions with a working group to test ideas and reach decisions about specific rooms and designs relevant to the resident group, we carefully convened an inclusive cross-section of residents: able, supported, with cognitive difficulties, and with varied cultural profiles.

Surveys

SurveyMonkey quizzes helped us elicit detailed advice from staff and families about their experiences and needs, which informed the design process as well as design decisions.

Functional assessments and prototyping

For this phase we found a mix of mechanisms including plan/space reviews and prototyping helpful in testing specific design-related issues and delivering a home-like, resident-focused facility.

Creating vibrant communities methodology

A key focus for our practice across all sectors – from seniors to education – is to consider the project’s broader urban design context and community engagement opportunities. To that end, we go beyond traditional architectural roles to help our clients with their research and help them build the relationships they need with Councils, service providers and financial consultants. It’s a partnership-based approach that yields innovative results, like a multi-generational seniors design we’re currently collaborating on which combines aged care with training for university students and child-minding services.

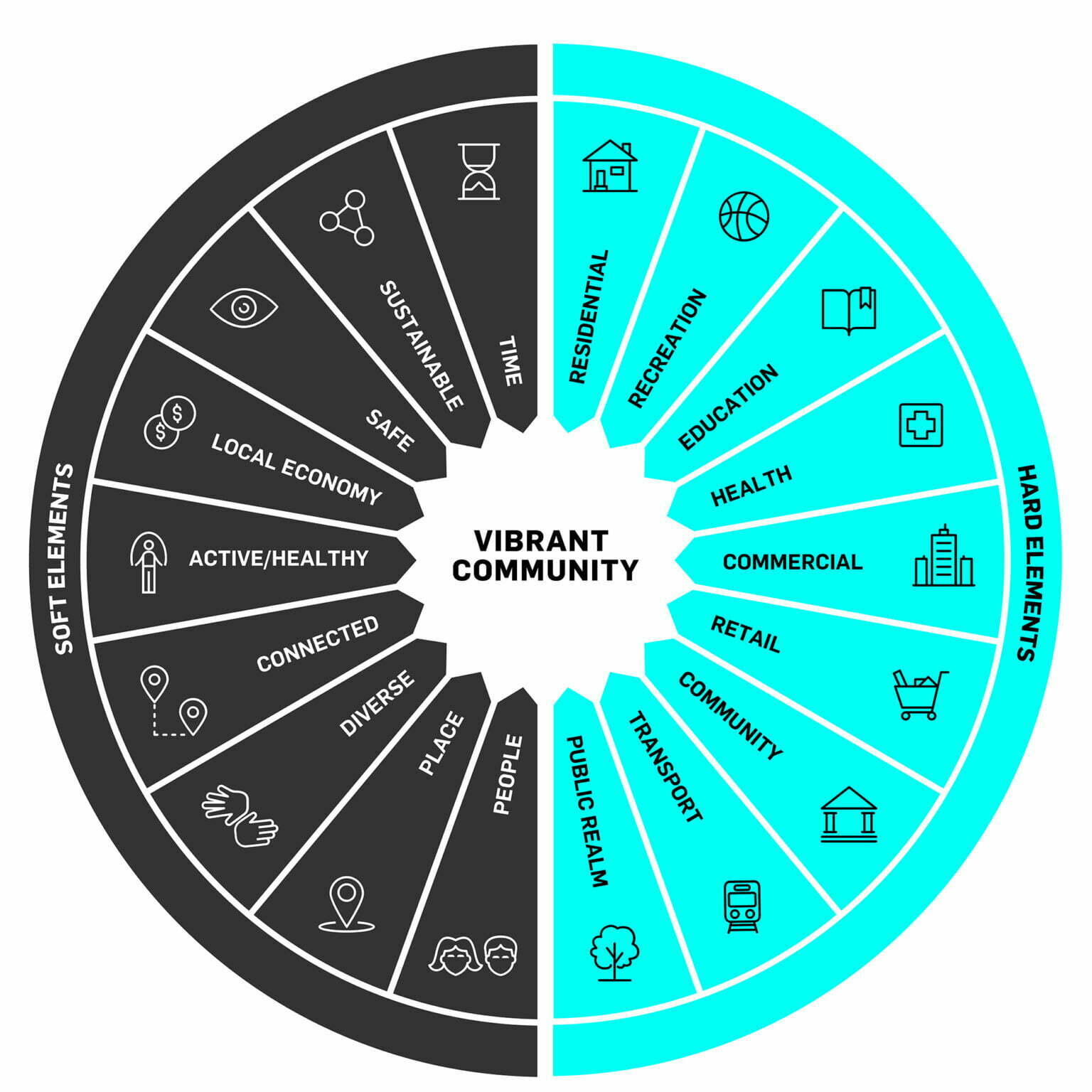

Over the past decade, our practice has developed a distinctive methodology grounded in masterplanning principles, which is explored in-depth in the book Creating Vibrant Communities by Dean Landy, the partner leading our urban design and mixed use teams.

Our Seniors Living & Care team applies these principles to our projects, using CVC workshops to systematically tease out the tangible and intangible elements central to great placemaking, explore how to apply them on this particular project, and arrive at a shared vision that guides the whole project team – clients, stakeholders, designers and consultants – from design to delivery and activation.

On a current project, our CVC workshops identified four pillars:

- Connected to community

- Vibrancy through scale

- Technology as an enabler

- Resident-first innovation

They also created targets for every element on the CVC wheel, which shaped our shared vision. A couple of examples are:

People

- Residents feel they have a life worth living, where they are at the heart of all decision making.

- Staff are engaged with their work and able to create meaningful connections with residents.

- Families are comfortable knowing they are sending their loved ones to a safe place where families are also welcome.

- The diverse range of ages and abilities have been considered and catered for.

Active/Healthy

- There is a platform for families to share in a partnership of care through the provision and enjoyment of everyday activities.

- There are accessible spaces for residents and local seniors to engage in physical activity that suits their needs and abilities.

- Outdoor spaces provide passive and active recreation opportunities for all age groups.

- Biophilic design brings a sense of wellbeing through considered connections to the natural world.

Exploring small households and hybrids

Since the Royal Commission, our industry has understandably been focused on the potential of small household models of between 7 and 16 residents to deliver the home-like intimacy of scale and experience that seniors and their friends and families seek and deserve. As designers we support small household models and celebrate the success stories emerging in Australia. But since well before the Commission, in our work with government, community and for-profit developers operating in quite different urban and regional contexts, we’ve also found many benefits in hybrid small household–intimate neighbourhood models, which allow larger operators to adapt in ways that are commercially sustainable.

Grouping several intimate residential neighbourhoods around shared food or care hubs, for example, can create both the intimacy of scale and efficiency of spatial planning to allow for more than 16 residents overall, while actually increasing the time staff have to engage meaningfully with residents. Hybrid small household models are obviously endlessly adaptable, but we’ve found the best all feature six key characteristics:

- Clear separation between resident and service spaces

- Communal areas of varied scales and of varying use

- Smaller nooks for casual interactions and quieter chats

- Domestic or island-style kitchens, accessible to residents and visitors

- Space to welcome family into the residential domain

- Gradation of public, semi-public, semi-private and private areas

Design guidelines

Designing collaboratively means we’re learning constantly, which makes our constantly evolving Design Guidelines for Seniors Living & Care central to our process. Our team is constantly refining and updating our succinct, highly visual guidelines, which aim to capture everything from guiding principles through to detailed dos and don’ts when designing and specifying. The following are the most useful strategies we’ve found to create home-like, non-institutional residences for seniors are:

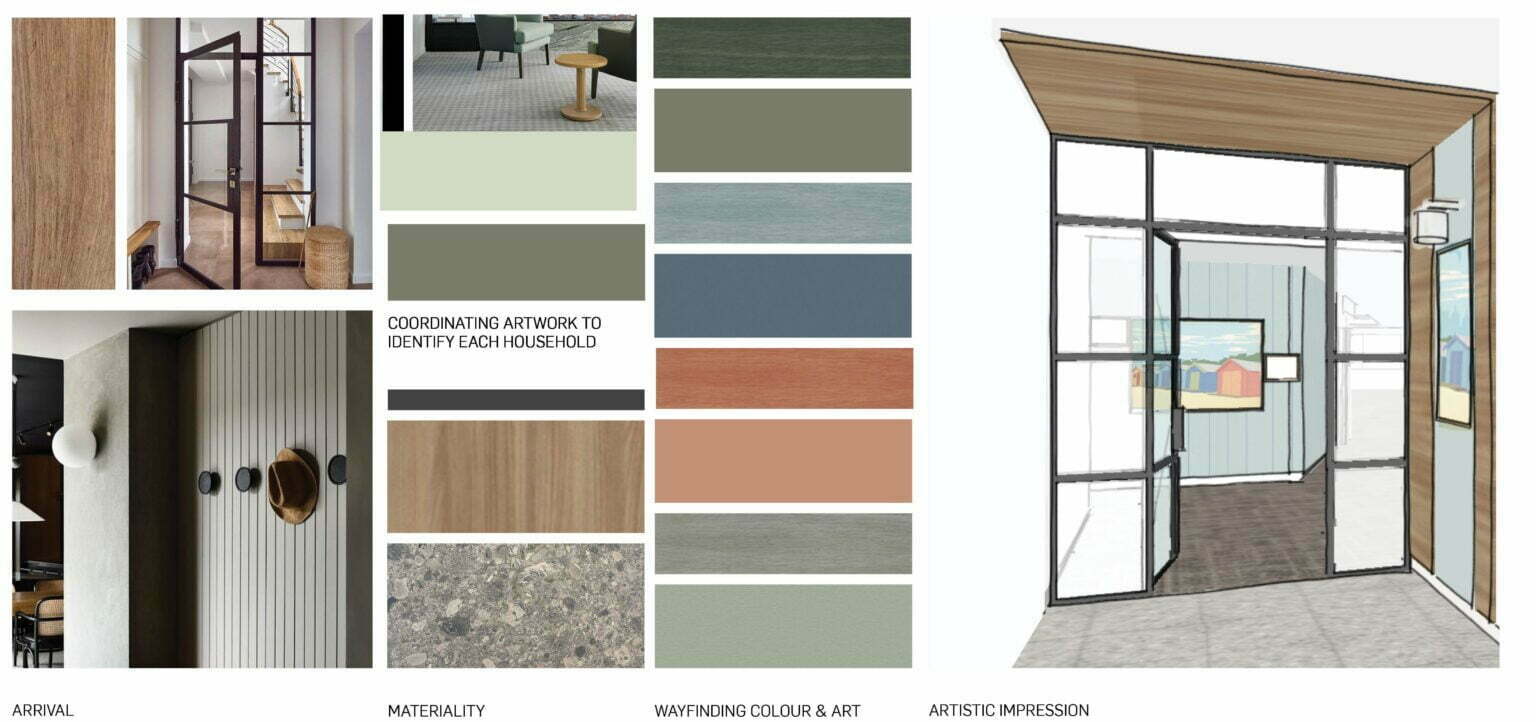

Materiality and wayfinding

In very broad terms, we use a timeless, durable and natural-look base materials palette and complement this with warm timbers, subtle patterns, acoustic texture fabrics, feature colours and graphic elements. But we’re careful to balance the need to create a contextually relevant identity for the shared spaces and individual residences with a more calming neutral palette that allows residents to personalise their space with their belongings. As a designer and as a daughter I was heartened to see how bringing in her couches, tables, paintings, photo frames and lamps from home helped Mum settle into her care facility and feel more at home there.

Balancing and controlling stimuli

We work closely with organisations like Dementia Australia to ensure our designers understand the huge range of experiences possible with dementia, from muscle weakness to brittle bones, hallucinations and changes in vision, hearing and spatial orientation. We’ve learned that designing dementia-friendly spaces involves many strategies that benefit all residents – and staff and families too in many cases. This includes allowing residents to control their level of stimulation in any particular moment, designing in ways that strike the right balance of sensory experiences throughout a facility, and employing intuitive and basic wayfinding to maximum effect. The latter may involve the use of colour or themed artwork to identify different floors or households in a facility, as well as design elements like thresholds, landmarks, focal points and icons or pictograms offering colour and contrast.

Technology

Non-invasive technologies like in-floor sensors can be useful in helping designers and staff understand precisely where residents are choosing to go and when, and what they’re choosing to do for themselves, which can help us design and activate spaces that offer them greater autonomy and better suit their personal preferences.

Other technologies, like virtual holidays and interactive pets, can be useful in creating a journey or personal connection to help isolation and loneliness. My mum loved the companionship and focus of a cute, interactive seal robot at her facility – a great way to lift residents’ spirits.

Ultimately, as architects, I think the greatest contribution we can make to seniors’ happiness through our work is to design not for stereotypes of ageing around degeneration and despondency, but for growth, independence and intergenerational interdependence. In the end, that benefits all of us.

Jennifer Rodezno is a Senior Associate at ClarkeHopkinsClarke Architects, who brings broad experience in practice development, educational design and staff mentoring to her role in Seniors Living & Care.