Interior architect, PhD candidate and caregiver in disability, Ilianna Ginnis argues for recognition of individuals with non-verbal and diverse communication, and the need to incorporate appropriate engagement and interaction into the design process.

Communication is a critical aspect of our work as designers. It enables expression and facilitation of needs and desires within space. What happens when our communication is not heard? Or, rather, not seen? How can design, as a multidisciplinary field, recognise diversity in communication needs?

As a sister to an individual who is non-verbal and who has an intellectual disability, I grew up with a deep understanding and empathy for those with diverse communication needs. Assisting my younger sister to communicate became my life passion. This has directed my career path and enabled me to further assist individuals with similar communication difficulties.

After graduating both as a caregiver in disability and an interior architect, it became evident to me that individuals who are non-verbal and who have intellectual disabilities are not recognised within the processes of design. This is possibly due to diversity in communication – but how can designers construct public and private spaces without the consideration of the users it aims to support? How can diverse cognition and perspectives be considered in design processes that are inflexible in their nature?

As a recent graduate and new practitioner, I am passionate about creating systems that are inclusive of people with intellectual disability who are non-verbal. It’s important that these systems support all people to attain agency, enabling them to be authors of their own narrative, as well as in communicating their needs and desires. My PhD aims at examining existing forms of non-verbal communication, which will guide the development of design methodologies that will provide a platform for non-verbal individuals to be ‘heard’. Additionally, my PhD aims at educating designers on how we, as practitioners, can become more aware of the diversity in communication, and how we can read behaviour and be inclusive of a person’s needs in space.

The problem is not in the communication. It is in the lack of recognition of diverse communication, which design has still not considered.

Colin Griffiths, through his doctoral research in intellectual disability and communication, highlights how “behaviours of people with profound intellectual and multiple disability whose communication may be difficult to interpret are at risk of being ignored”.1 Griffiths suggests that if all behaviour has the ability to be communicative, then there is a requirement for “observation, interpretation and understanding”, allowing communication to become more than just attempting “understanding” but further offering opportunity for interpretation. This could be applied to design practice, enabling users to be represented and recognised in design and spatial needs.

In communication, especially non-verbal, the ‘feedback process’ is essential for engagement.2 Non-verbal communicators rely on facial expressions, gestures and modelling for exchange of information. This can be applied to processes of design where behaviour is the main ‘voice’ in the conversation. A great example of inclusion of non-verbal communication in the design process is choices – offering the individual two sample textures or materials and observing their response. Another is observing the user in their space to gain an understanding of personality.

Are they walking around feeling textures and materials on the walls on their own? This may indicate they are extroverts and attain some sort of confidence in space, with little need for reassurance. Or, does the user cuddle up close to their parents/caregiver and hold hands, bringing objects close to their face to smell or feel textures more intimately? This would indicate a more introverted personality, which perhaps prefers familiar spaces, people and objects. This is reading the behaviour of the user as a language.

Non-verbal communicators’ intentions and symbolisation differ from person to person. These forms include “generalised movements and changes in muscle tone, vocalisation, facial expression, orientation, pause, touching, manipulating or moving with another person, acting on objects and using objects to interact with others, assuming positions and going to places, the use of conventional gestures, depictive actions, withdrawal and aggressive and self-injurious behaviour”.3 Additionally, there is pre-symbolic communication, which is behaviour that is more complex in interpreting and understanding. These forms of communication are “developed by the individual” themselves. There is potential to understand these behaviours, but this may require the building of connection and relationships, which takes time.

It all starts with the user. Who are they? How do they communicate? Who is their support network?

Kilmiston Respite

Towards the end of 2019, I was commissioned by St Mary’s Health Care Services, a disability caring agency, to redesign their respite home for individuals who are non-verbal with intellectual disabilities. As a designer, I wanted to take a different approach than traditional design processes, and therefore used methods of communication used by the specific individuals. A traditional design process follows a series of design phases that are driven more towards the outcome of the project. The designers communicate with the client verbally, through regular meetings. The process includes verbal and written feedback as well as limited engagement with the user. The design process is therefore created to respond to neurotypical forms of communication, making the design process exclusive to neurodiversity and communication.

Following a unique design process that used multiple forms of communication and aids, I independently worked with the users and their network, understanding their preferred communication style as well as their likes, dislikes and spatial needs. These included:

- Object to symbol – using physical objects to communicate. The individual may bring an object to you or use it in correlation with a picture to express an action or need. For instance, bringing you a remote to change the temperature of the room.

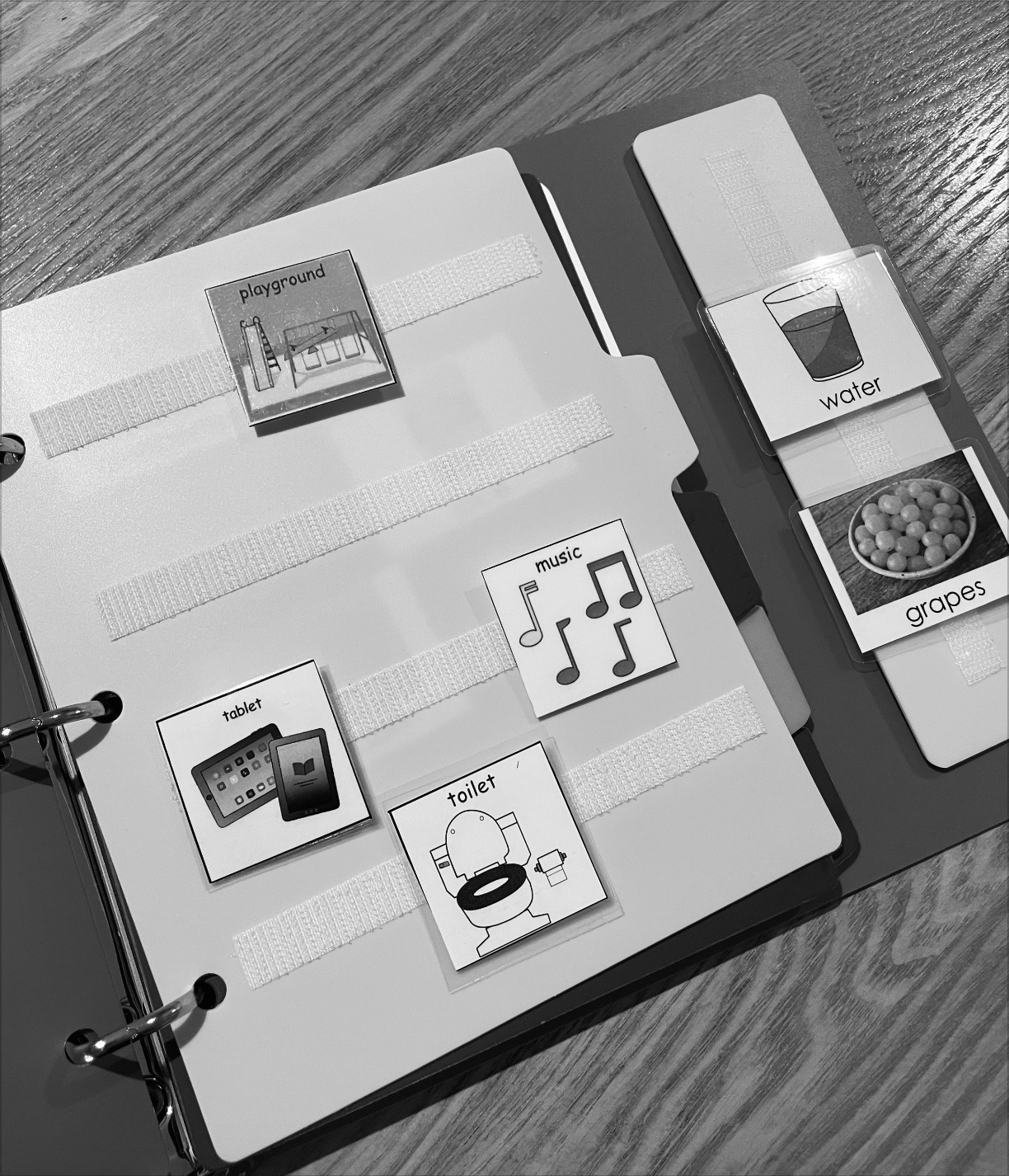

- Pecs (Picture exchange communication) – users communicate through visual imagery and illustration. The pictures make reference to what they are trying to communicate – for instance, the picture may show a particular food that the individual wants to eat.

- Choice boards – similar to pecs, a user will have a series of cards with illustrations or graphics and can choose which one they prefer. For this project, it was interesting to see the choices in colour and material through the choice board communication system.

- Communication book – a diary with categories relating to discussion. The illustrated images allow the user to pick in context of the communication topic/thematic.

- Makaton communication system (where the individual uses signage to express needs) – this includes a series of gestures aimed to express a need or to communicate a desire. The gestures are simple, allowing an individual to communicate efficiently.

This photograph resembles the user’s likes and needs. The user communicates a need for outdoor space, his technology to assist his communication, calmness after a long day to wind down, and the importance of music in his life. Additionally, he requires assistance with the toilet, which was important to his needs in the space.

Additionally, with all these communication styles, I took into account behaviour and its ability to communicate. Non-verbal communication is expressive, using a variety of gestures, movements and vocalisations to express needs. As a designer, I wanted to allow access to communication for these users. Sometimes users are sensory seeking, meaning they look for textures and materials that cause a certain level of stimulation and feedback, during engagement. Providing sensory equipment supplied by occupational therapists assisted in keeping them engaged and allowing an individual to communicate with desired equipment. At other times, users may be sensory avoiding, meaning too much stimulus information – such as textures, noises, colours and tastes – may cause discomfort and distress in the user. It was important I understood the individuals’ likes and dislikes while communicating.

The design process allowed users to test the existing conditions, enabling me as a designer to understand what the space needed to meet needs and desires.

One of the important phases within my process was the observation. I examined what the individual liked and did not like, how they communicated, what their precursors were for communication, what happened before and after they communicated, and what they were sensory seeking. When observing an individual with non-verbal communication abilities, so many factors influence their behaviour. Therefore, it is important to view it holistically. Through observation, a designer is able to attain information about the user.

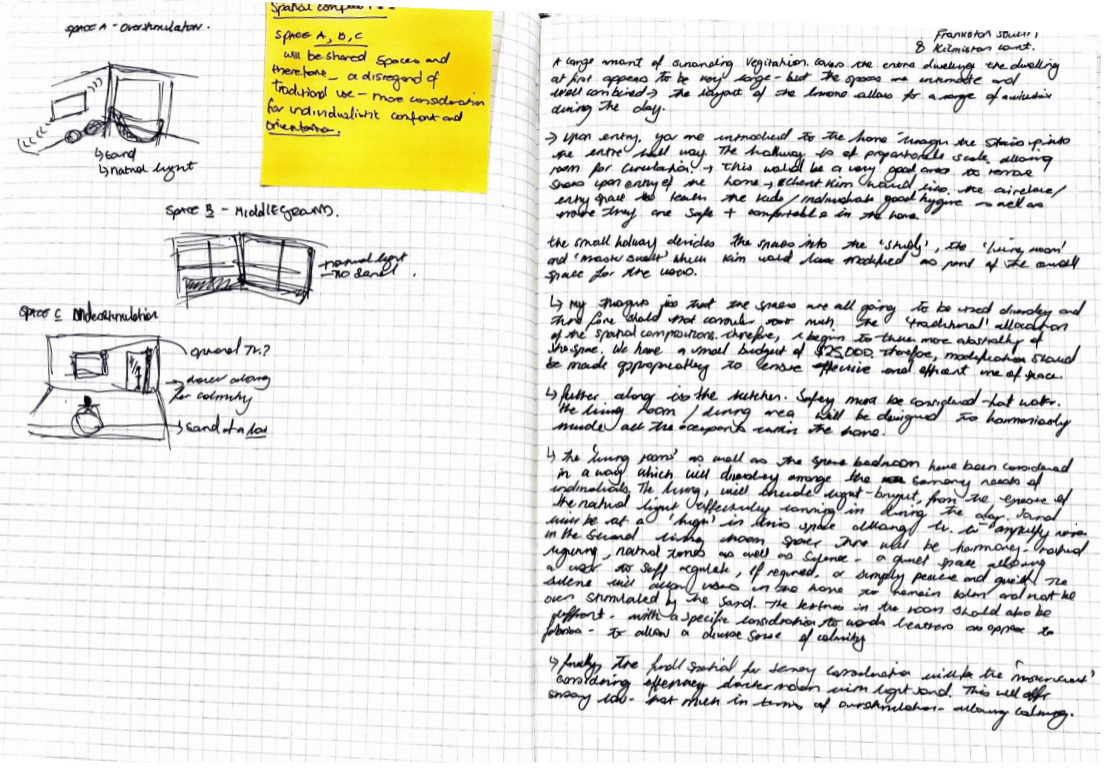

The space took into consideration sensory elements to offer calming and ease. Every user has their own desire for calm and sensory stimulation. The use of natural materials had been incorporated within the spaces and a neutral colour palette offered harmony. Materials were tested with users, offering them a combination of hard textured surfaces, reflective smooth surfaces and soft materiality.

The spatial layout and composition was designed with the user, focusing more on needs and desires rather than conventional and traditional uses of space. The design worked with these intimate moments and interesting qualities – for instance, the shadows on the wall during the day, reflecting the leaves from the garden. I observed that individuals gravitated towards these moments during the day and incorporated them as part of the design.

The natural colour palette allowed for limited contrast and no overwhelming colour tones. Textures were chosen on the specific setting of the space. The rooms were divided based on their sensory qualities. For instance, one of the rooms allowed for high sensory stimulation; therefore, textures were ‘fluffy’, soft and compressible. In another room, textures consisted of leather finishes, hard polished timber and exposed brick, all of which reflected sound, therefore acting as a quieter space – limited sound and finishes offered an atmosphere of stability. The space was designed for flexibility, so the user could change the sensory qualities of the space when they desired. An example of the flexibility in the space included lighting and sound. These could be played around with to meet users’ stimulation and sensory needs. Another example was the furniture, making it easy to transport from one room to another to create a balance in sensation.

In other instances, I took into consideration that people would want a darker, more mellow space, and therefore integrated rooms with minimal lighting. These rooms also comprised soft finishes, further allowing compression for sensory relief or overstimulation. Most importantly, the rooms are adaptable. They can be interchanged depending on the user of the space at the time and their desires and needs. The respite project had complexities in considering multiple user needs.

The space was designed with the user and this has the potential for a rich design process. The user became central to the process, allowing the design to reflect their perspective on the world.

After the project was completed, it went through an evaluation phase to examine if the users were happy with the results. Feedback was collected from the families and the individuals residing there. Families observed a decrease in anxiety and users were excited to attend the respite. As a designer, I want to make sure I revisit the project for further evaluation. User needs and behaviour will inevitably change, and the space needs to reflect these changes to suit user needs.

I want to create recognition of individuals with diverse communication. Designers can model these forms of communication in design processes to offer opportunity for engagement and interaction, enabling inclusion within design. Communication access is extremely important and relevant, particularly within the practice of design, where expression of needs, desires and function is crucial to the user. The next step is for the receiver of the message to accept these forms of communication to allow for inclusivity and communication access.

Ilianna Ginnis is an Interior Architect (Honours) and a current PhD. Candidate within the Design Health Collab at Monash University, and a caregiver for persons with disability. Ilianna has experience within specialist schools as a caregiver and teacher’s assistant with many disability agencies, as well as personal lived experience as a sister. As an emerging designer, Ilianna is passionate about engagement, participation and the response we have to architecture and the interior, using a fusion of visual receptivity and useful purpose, both in the tangible and intangible sense. Her current PhD speculates on how design processes begin to consider persons with severe and profound intellectual disability and non-verbal communication, allowing designers to integrate users into complex processes as narrators of their own experience, as well as enabling representation within the design, eliminating possible marginalisation, offering agency to persons with intellectual disability.

PhD Supervision: Dr. Chris Cottrell, Professor Daphne Flynn and Dr. Kanvar Nayer

- Colin Griffiths and Martine Smith, “You and Me: The Structural Basis for the Interaction of People with Severe and Profound Intellectual Disability and Others,” Journal of Intellectual Disabilities 21, no. 2 (2017): 103–17.[↩]

- Ross Buck and C. VanLear, “Verbal and Nonverbal Communication: Distinguishing Symbolic, Spontaneous, and Pseudo-spontaneous Nonverbal Behavior”, Journal of Communication 52, no. 3 (2002): 522–41.[↩]

- Griffiths and Smith, “You and Me”.[↩]