Monash University’s XYX Lab workshops ideas for a safer, more welcoming Melbourne for women and girls.

Women and Girls in Urban Space

Uneven development in cities across the world means that city spaces are inclusive of some people while simultaneously exclusive of others. Urban areas then become defined by their patterns of exclusion and inclusion, which may be based on a multifarious range of factors reflecting power differentials, from socio-economic status to age, from ethnicity to mobility.

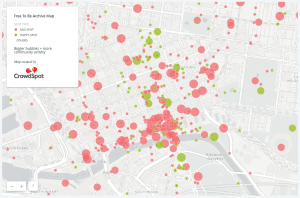

The degree to which the experiences of women and girls in neo-liberal cities are limited as a result of their gender was uncovered in a recent pilot project created by Plan International Australia in partnership with Crowdspot and the interdisciplinary XYX Lab at Monash University. The Free to Be map allows young women and girls to drop a ‘good’ pin on the locations in the city that they like and a ‘bad’ pin on the areas where they feel uncomfortable or unsafe.

Free to Be was designed in consultation with young women who were asked to identify where in Melbourne they felt safe and welcome, or unsafe and unwelcome. The map allowed women and girls to tag these places in the city, with an option to accompany the pin with a short statement in order to share their experiences of specific spaces and places. The final map was crowdsourced over a three-month period from October to December 2016 and gathered over 1,300 pins documenting these perceptions of safety. A further 600 plus statements supported the pins with comments. Safe and unsafe clusters and hotspots were quickly identifiable. By spatially highlighting the mechanisms of women’s exclusion, this initiative begins to reveal a range of propensities in urban space that limit access: ranging from the economic to the political, the legal to the implicit, and the subtle to the openly violent. These varying perceptions and experiences of safety for women very much influence their engagement with a city. In response, how might feminist design tools offer alternative approaches to creating more gender-sensitive and equitable design of urban space?

Free to Be Archive Map – happy and sad places. Data from Crowdspot.

Crowd-Mapping: A Feminist Method

Recent international initiatives that challenge sexual violence against women in urban spaces have utilised geolocative methods to collate and share data. The crowdsourcing method facilitates and streamlines the “processes that are required to generate data about socio-spatial perception and experiences”.1 The use of this technology encourages women and girls who have experienced or fear sexual violence to disclose the location, context and details. The data generated is termed geosocial and is made up of points that are created and tagged to a precise geographical location. When aggregated and freely available to the public, crowd-mapping surveys extend innovative social media activism and, when used to harness female collaboration, provide a uniquely feminist and female lens.2

This method of crowdsourcing sits alongside a movement in international activism – or “crowd-feminism” 3 – that has begun to document sexual violence against women in urban spaces. Projects like Everyday Sexism (UK), Safetipin (New Delhi, Jakarta, Bogota and Nairobi) and Harassmap (Egypt, India and other countries) all use geolocative smart technology. The benefit of this method is that once “these internal worlds become public, urban space is re-configured”.4

This technology encourages women and girls to disclose details in their own time and “in their own words, without the restrictions on narrative form associated with the traditional justice system”.5 The social media activism enabled by publicly available crowd-mapping surveys may serve as both a campaign method and a means of capturing the impressions of a space.6

However, although this kind of activism has great potential to give detailed spatial information, it seldom reaches the potential of transforming the urban environment.7 Indeed, the sheer volume of data collected by this method can pose immense problems for analysis.8 Similarly, if the information is simply collected but not analysed, or analysed without subsequent findings being acted upon, women sharing their experiences may actually feel increased fear and self-exclusion. Without analysis, action or response to the collectively highlighted issues and spaces of risk, gender inequity in urban spaces persists.

Feminist crowd-mapping captures the capacity to reveal shared yet diverse female and feminist voices and – as with the work in the discussion that follows – the possibility of undertaking deeper collaboration between stakeholders that might initiate new urban projects capable of addressing the needs of diverse populations. The benefits of combining geolocative crowd-mapping with design-based solutions provides tangible outcomes and real-world impact.9

In the case of the collaboration between XYX Lab, Plan International Australia and CrowdSpot, the Free to Be project uses the insights of women and girls to shape the design, redesign and communication of this concerning urban issue.

“Free to Be Design Thinking”: From Data to Action

The “Free to Be Design Thinking” workshop invited participants from all sectors of the community, with different jobs, ages, socio-cultural backgrounds and, most importantly, with diverse experiences and possibly conflicting perceptions of the same city.

The workshop aimed to outline a series of well-thought-out proposals for how the information and momentum built through the Free to Be mapping project could impact Melbourne. These proposals included policy recommendations, physical and tangible interventions, and experiences and events aimed to progress women and girls’ experiences in cities.

Importantly, the “impact ideas” developed throughout the day were created together by all the participants in the workshop. This means instead of the XYX Lab proposing ideas as architects and designers, the Lab instead relied upon those in the room: on each and every participant’s own lived experiences of the city, both personal and professional. Participants built upon each other’s differences by using the creative, hands-on approaches that the designers in the XYX Lab use to navigate complex problems.

The workshop was structured in four stages: understanding the context, coming up with ideas (ideation), thinking through and refining those ideas by visual means (visualising), and physically building and making things in order to present and discuss those ideas. At the beginning of each section, “play” activities were introduced to help break down existing barriers to thinking and interacting.

All the participants were divided between tables in a way that deliberately grouped strangers with varied experiences and perspectives. Right away, participants were asked to express themselves both verbally and through making. Each person was given a tetrahedron template that they could make into a 3D form to use while introducing themselves to their work group. This template asked participants to reflect on who they were and why they were at the workshop. Through this process we discovered we were a room full of [empathetic, caring, determined, passionate, creative] people who used [creativity, analysis, communication, inclusion, strategies] to solve problems, and spent our working days [connecting, developing, creating, engaging publics, organising]. More importantly, we were there combining those strengths and passions to think through ways to make Melbourne a better city.

Facilitator Zoe Condliffe, the Campaigns Officer for Plan International Australia, outlined the origin and development of the Free to Be map, ensuring that all workshop participants had a fundamental grasp of the project.

Analysis of Free to Be data by Dr Gill Matthewson. Photo by Gill Matthewson.

Facilitator Dr. Gill Matthewson approached the data provided by the Free to Be map by assessing the collective reasons why the young women designated places happy or sad, and safe or unsafe. The varying geographic patterns of these reasons were plotted in a number of different ways. This research found that, although locations shared reasons why they were reported to be considered safe or unsafe, the pattern for each location was unique. For example, poor physical conditions were the main reason for negative pins in some locations, and in others the physical conditions were not reported but sexual harassment was high.

Facilitator Dr. Pamela Salen closely observed the physical messaging in terms of the branding signage, advertising and language used in a number of the areas that were designated either happy or sad. Her analysis revealed patterns that may be contributing factors to a feeling of safety or lack of safety in these areas, including: masculine and feminine language and graphics and clusters of types of services, such as fast-food chains.

Brand & Advertising Analysis by Dr. Pamela Salen. Photo by Pamela Salen.

These presentations served to provide everyone in the room with a common baseline understanding of the issue. After hearing these presentations, participants were then asked to consider other ways of looking at the map and how the project could inspire changes and impacts. They were asked to suspend judgment and produce as many ideas as possible. These ideas were then organised according to whether they were political, experiential, digital, physical or other. These headings helped reveal what types of interventions and ideas were coming to the fore, but also demonstrated how interconnected the seemingly disparate contributing factors are within this wicked problem. Once all the ideas had been collected, each group voted on the strongest impact ideas for further discussion. The remaining ideas were collected and later analysed by the team to reveal trends and capture all the individual and collective thoughts of the workshop.

Each small group was provided with a guide to mapping out the story of their impact idea. This was a timeline that helped show the transformation of the impact idea into a reality. Groups began with prompts that helped them examine the current situation, and ended with producing a view of what the city would look like after their impact idea had been fully and successfully implemented. The space in between these points was the critical part of the timeline, as groups thought through and mapped out the steps that would lead to successful completion. In considering what resources might be required and what challenges and opportunities might be raised by the idea and its implementation, participants began to plot the transformation timelines. This process of thinking through how an idea might be implemented necessarily has tentative moments that need to be embraced, discussed and/or debated. The workshop emphasised the provisional nature of design thinking to negotiate these moments.

Re-Imagining the City

Throughout the day a colourful paper model of a city sat at the front of the room. Textures, colours and signage evoked the city of Melbourne, but the model was arranged into a generic urban layout. The pieces of this version of the city were taken apart and used to build a new vision of Melbourne, imbued with meaning. Each group used the pieces to construct a model of how their idea would improve, change and contribute to a safer, more inclusive Melbourne. They did so by ripping, tearing, folding, taping, drawing and making a future version of the city to visually represent the impact and consequential effects of their idea.

While the models ranged from literal to abstract, each represented concrete and tangible ideas for a more inclusive city. These models were joined together at the end of the day with each group explaining their impact idea to make a new vision for Melbourne. The presentation order was not predetermined. Each group took their cue from the presentation of the preceding group. This process demonstrated how the ideas supported or reinforced others and how a fluid narrative around a shared ambition – to make Melbourne a safer place for everyone – could be realised through a number of diverse, but interconnected ideas.

Co-design is often seen as an equalising force, creating inclusion and addressing power dynamics in small ways, as the approach disrupts and “contests dominant hierarchically oriented top-down power structures” by requiring “mutual learning between the stakeholders/actors”.10 When addressing wicked problems, such as unequal gendered experiences of a city, bringing together diverse and underrepresented voices is crucial. This workshop brought together young women, designers, architects, government officials, and members of the police force and public transport to co-create a shared vision. Rather than a reactive afterthought, the ideas were future-focused and placed the safety of women at the forefront of the discussion. Building on the foundational awareness of women’s stories from the map, the framing of this issue as an important community responsibility represents an alternative approach to placemaking.

The key goal of the XYX Lab at Monash University is to produce knowledge about how space and design shape the causes, consequences and approaches to understanding, controlling and preventing gender inequity in Australia. Led by Director Dr Nicole Kalms – and with the combined strength of the core members – Dr Gene Bawden, Dr Pamela Salen, Dr Gill Matthewson, Allison Edwards and Hannah Korsmeyer – the Lab communicates through innovative mediums to speak not only to practitioners and scholars in design, architecture and urbanism, but also to those working in policy and social services.

This article first appeared in The Site Magazine, Volume 38: Feminisms, and is republished here with permission.

- Matthew James Kelley, “The Emergent Urban Imaginaries of Geosocial Media”, GeoJournal 78, no. 1 (2013): 185.[↩]

- Nicole Kalms,“Digital technology and the safety of women and girls in urban space: Personal safety Apps or crowd-sourced activism tools?”, Architecture and Feminisms: Ecologies, Economies, Technologies, eds. Hélène Frichot, Catharina Gabrielsson and Helen Runting (London: Routledge, 2017), 10[↩]

- Sara Rabie, “Crowd-Feminism: Crowdmapping as a Tool for Activism” (Master’s thesis, Goldsmiths University, 2013), 40–43.[↩]

- Kelley, “The Emergent Urban Imaginaries of Geosocial Media”, 184.[↩]

- Bianca Fileborn, “Special report”, Griffith Report Law and Violence 2, no. 1 (2014): 45.[↩]

- A.T. Crooks, A. Croitoru, A. Jenkins, R. Mahabir, P. Agouris and A. Stefanidis, “User-generated big data and urban morphology”, Built Environment 42, no. 3 (2016): 396–414.[↩]

- Reinout Kleinhans, Maarten Van Ham and Jennifer Evans-Cowley, “Using social media and mobile technologies to foster engagement and self-organization in participatory urban planning and neighbourhood governance”, Planning Practice & Research 30 (2015): 237–47; Melanie Lambrick, “Safer discursive spaces: Artistic interventions and online action research”, in Building Inclusive Cities: Women’s Safety and the Right to the City, eds. Carolyn Whitzman, Crystal Legacy, Caroline Andrew, Fran Klodawsky, Margaret Shaw and Kapana Viswanath (London: Routledge, 2013).[↩]

- Michael Batty, “Big Data and the City,” Built Environment 42, no. 3 (2016): 317–320.[↩]

- Kalms, ‘‘Digital technology and the safety of women and girls in urban space”, in Architecture and Feminisms; Lambrick, “Safer discursive spaces”, in Building Inclusive Cities.[↩]

- Alastair Fuad-Luke, Design Activism: Beautiful Strangeness for a Sustainable World (London: Earthscan, 2009), 147.[↩]