Karen Burns looks back at 1970s Melbourne and shines a light on the important work of Deborah White and others building community institutions in the late modern city.

In 1975, Australian architect, academic and activist Deborah White was commissioned to write an essay on ‘Women and Architecture‘ for a themed issue of the literary cultural journal Meanjin. The special women’s issue was a local response to the United Nation’s designation of 1975 as International Women’s Year. White’s essay is the earliest public manifestation of the impact of second wave feminism in theories and histories of Australian architecture. She catalogues women’s long-standing minority place in the profession. Her article is also a significant contribution to the furious mid-1970s debates on the nature and future of architecture. In the following essay, I set Deborah White’s theoretical response to the architectural crisis in the context of her urban activism and alliances with fellow dissidents. Together with Ruth and Maurie Crow, Winsome McCaughey and others, White sought to rebuild communities in an inner city debilitated by official neglect, bureaucratic over-reach and poverty. Deborah White’s forgotten activism and architecture (with her buildings co-designed with Greg Burgess) is one of many hidden Australian histories in urgent need of recovery.

Bronze Medal Dissent

Australian architecture’s values and commodity status were explicitly called into question from mid- 1975 to mid-1976 in a furore sparked by the 1975 Royal Victorian Architecture Medal [1. I would like to sincerely thank Deborah White and Greg Burgess for their generous assistance in the preparation of this paper.]. Fervid newspaper coverage, bold professional journal articles and feisty, companionate pieces in the literary magazine Meanjin galvanised local dissent over the terms and practices of late modern architecture. It’s important to compare the two Meanjin essays – separately authored by Deborah White and the late Peter Corrigan – before setting White’s account in context to understand how inner urban networks, gendered activism and actions shaped her feminist critique of modernism and architecture. Her engagement in inner-city social movements and citizen pursuit of amenities for local communities establishes a different genealogy for late modern architecture’s identity crisis. Mapping White’s social networks and spatial practices locates the rejection of architectural “monuments to Capital” within urban communities and their experience of an alienating late modern city in a world linked to, but beyond disputes within the architectural confraternity.

In mid-1975, the Royal Victorian Institute of Architects awarded Yuncken Freeman’s Melbourne BHP building its most prestigious prize1. The following year Melbourne architect Peter Corrigan wrote a polemic on the award decision and the building titled “Bronze medal and brute steel” for the literary magazine Meanjin Quarterly[3. Peter Corrigan, “Bronze medal and brute steel: BHP building”, Meanjin Quarterly, Autumn 35, 1 (April 1976): 34–41.]. Corrigan dissected the architectural values and professional responsibilities enshrined in the sleek, black corporate tower. At the award ceremony, he wrote, the announcement of the prize to BHP was greeted with “boos and hisses”; and favourable and dissenting views of the building were canvassed in a subsequent newspaper article in the city’s most prominent daily2. BHP was also the target of another architectural essay in Meanjin, Deborah White’s “Women and Architecture: A personal observation”, which appeared five months before Corrigan’s essay3. White’s article is the first feminist publication on architecture in Australia4. In passing she used BHP as a trope for marshalling her critique of the profession and the social role embraced by many architects. She dismissed the building as an “extravagant Neo-Classical monument to Capital”, and added: “An indefensible amount of our personal resources are being expended on extravagantly commercial and institutional prestige buildings of irrational design”5. Corrigan, too, complained that the BHP building endorsed architecture as a particular kind of “product”: the short-term commodity6. Both White and Corrigan proposed non-market relations as the basis for a compact between people and buildings.

Corrigan and White’s essays were companion pieces in the growing Australian and international disquiet around modern and late modern architecture. The BHP medal was Melbourne’s Pruitt-Igoe moment, as storm clouds gathered around a building that could visibly embody signs of crisis, failure and fracture. Corrigan’s “Bronze medal” urged architects to understand that they had the capacity “to change the nature of our institutions”6. Deborah White was also interested in advancing a different social agenda for architecture and staking out an alternative domain for architects. Corrigan drew briefly on theatre as arena for rethinking the architectural project but rejected recent extra-disciplinary explorations, whilst White welcomed the expansion into urban studies, resource management and conservation, sociology and anthropology. Corrigan argued in humanist terms for the values of the “imagination” and the “spirit”, but White declared that women architects were excluded from dominant socio-economic patronage systems, and were already better placed to attempt to “fulfil” architecture’s “social and political responsibilities within the community”7. Architecture had mainly catered to “privileged beneficiaries”, she observed, rather than the multitude disadvantaged by a “hostile environment”. Brought closer “to the realities of human existence by their traditional direct involvement at the family and neighbourhood level”, women were already working within this sphere. For White, the “community in general, and not individuals and institutions or even ‘Architecture’ in particular . . . is the proper object of architectural concern”8. Both Peter Corrigan and Deborah White were interested in forming new organisations and redefining architecture’s project after the BHP crisis. Peter Corrigan’s path and his story afterwards are well known, Deborah White’s much less so.

The “Women and Architecture” essay and its vision of women architects, family, community and neighbourhood contains the kernel of a different architectural history of the 1970s[12. A fine national, longitudinal study of Australian community buildings from the 1920s to the present-day is Community Building Modern Australia, eds. Hannah Lewi and David Nichols (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2010). The breadth of the historical span necessitates a reduced focus on the 1970s and 1980s.]. This history is now rising to the surface as a result of White’s engagement in an oral history project focused on Australian women architects who were active in feminist and community organisation, action and politics in the 1970s and beyond, in Melbourne, Sydney and Canberra[13. The focus of this current project might become larger.]. Like a number of her peers, White’s story takes shape within geographies of urban activism, as women architects and others “designed” new sorts of places in the urban landscapes of the late modern city. This essay gives a brief snapshot of this untold history by tracing White’s involvement in inner-city social movement networks pursuing amenities for local communities. Focusing on the struggle to gain community child care provision, this piece traces citizen actions, children’s “right to the city”, and new typologies developed in child care centre designs. Like the city itself, layers of history are revealed in this archaeology. White’s spoken memory record offers clues to a bigger urban history and contextualises the critique of architecture made in her Meanjin essay. Urban action and the networks of the city provided a space to form and act out a different vision of the architect and the architectural project.

Meanjin Quarterly 4, 1975. Cover image: Vivienne Binns, Girl on a Stick, Aged 16

The Activist City

Women architects’ contributions to Australian city culture included policy development, evidence-based critiques of state projects, work within activist organisations, design for sustainable buildings, critiques of energy consumption, and the establishment, design, and construction of childcare, refuge, health, housing and education facilities. Activists in Sydney and Melbourne worked in community-rich, but physically and economically dilapidated urban environments. In the post-war period, public and private finance had disinvested from the inner suburbs and neglected welfare and education institutions. Cheaper accommodation provided shelter to disenfranchised and disadvantaged groups. Working class people were joined by post-war immigrant communities in these suburbs, in urban landscapes still dotted with the factories, workshops, gasometers and waste dumps of the industrial economy. In the 1960s and 1970s, the large-scale demolition policies and estate building programs of State Housing authorities displaced communities. By the early 1970s, local citizens were organising resistance, although contests over government incursions had begun in the 1950s9. At the beginning of the 1980s, community organisers in inner-city North Melbourne argued that their “community fabric” had been “torn to shreds” by urban renewal, the relocation of industry, and reduced housing stock. Community, they declared, was being “re-knitted”10.

Alliances of activists, professionals and communities “built” places in the urban landscape for marginalised and excluded groups, including women and children, immigrant communities, homeless people, tenants of public housing, and indigenous Australians, constructing their own self-governing organisations. These groups were building new collective institutions, although the term would have been anathema in the period (see below). Corrigan had railed against the complacency of architects, and argued that they were in a position to change the nature of our institutions “by suggesting new forms to take” and “new kinds of space for them to occupy”. He was urging fellow architects to become active. The inner Melbourne Community Child Care organisation quoted urban sociologist Christopher Lasch: “Citizens must take the solution of their problems – the deterioration of child care, for example – into their own hands. They must create their own agencies of collective self-help, their own ‘communities of competence'”11. The 1977 Carlton publication on Community Childcare argued that “community refers to that process of interaction between people, knowing and being known, caring and being cared for, sharing, exchanging and trading and so on.”[17. Winsome McCaughey and Pat Sebastian, Community Child Care: Resource Book for Parents and Those Planning Children (Carlton: Greenhouse Publications, 1977), 1.] This vision of shared and exchanged community resources was distinguished from the organisation of resources by capital or the state.

These community resources were harnessed and traded at the level of the neighbourhood. The “social community” of a “neighbourhood clan network” countered the “hostile environment”, identified in White’s essay[18. Community Child Care Association, Child Care – Workable policies for working women (Fitzroy, Vic.: Community Child Care Association, July 1978), 3.]. For White, children were the most disadvantaged by a hostile environment and community childcare and the play spaces in these buildings and allotments offered a better environment for inner-city children[19. Child Care – Workable policies, 3.]. Women with architectural training – Deborah White, Lecki Ord and Barbara Wigley – used their building skills in tandem with Winsome McCaughey, the designer Mary Featherston, activist Ruth Crow, and many others to establish community-based care buildings and a child-care resource book in Melbourne. In a 1978 pamphlet on childcare for “working women”, the Fitzroy-based Childcare Association described a child’s confidence in, and knowledge of the people and places around her as the child’s “social “environment”. This can be contextualised within the framework offered by her Meanjin essay, as White interrogated the organisation of environments for the benefit of privileged beneficiaries.

White and the communities within which she was immersed were promoting rights-based access to the city, including asserting the rights of parents and children[20.Community Child Care Association, What is Community Childcare?, 2. It notes that the group is committed to ensuring that “children’s needs are met” and “their rights upheld”, and that the Community Child Care Association is “committed to meeting and upholding the needs and rights of parents”.]. The “liberation” of children was a project within the early feminist movement. In 1971 New York feminist Shulamith Firestone had used her groundbreaking book The Dialectic of Sex to proclaim that children as a “class” are “oppressed”[21.Shulamith Firestone, “Down with Childhood”, The dialectic of sex: the case for a feminist revolution (New York: Morrow, 1970), 81–118.]. Drawing on Philippe Aries’ history of childhood, she traced the historical emergence of the nuclear family and the development of the analytic category of the child12. Firestone exposed the schooling system and the family unit as major sites of the disciplining and subordination of children. In 1974, the Melbourne organisers of community child care grouped around Winsome McCaughey, distancing themselves from the “small, isolated, nuclear family” and the “authoritarian attitudes” of “the dumping depots and fortresses of institutionalisation”[23. Winsome McCaughey and Patricia Sebastian, eds., Community Child Care (Fitzroy, Vic.: Community Child Care Association, 1974), iv.].

Melbourne’s inner urban and middle suburban childcare movement was propelled by a number of issues, including the rising number of working mothers, concern for economically disadvantaged groups in which women had always worked, the isolation of first-generation migrant families from family care networks, and the desire for neighbourhood child care centres as generators of community identity and connection. Community had to be built and cultivated. The election of the radical Whitlam government in 1972 formalised these desires and funded them with the passing of the Child Care Act[24. The Child Care Act 1972 provided funding ($6.5 million for the first year) for “non-profit organisations (including local government bodies) to operate centre-based day care facilities for children of working and sick parents”. “Commonwealth Support for Childcare”, Parliament of Australia, Accessed 3 March 2016, www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/Publications_Archive/archive/childcaresupport.].

Childcare Actions in Inner Melbourne

In 1971, White, with a young baby and a teaching job in the Architecture School at the University of Melbourne, had started her own home-based child care group at her Victorian terrace house in St Vincent Place North, Albert Park13. Though she lived south of the CBD, she worked north of the city in Parkville. She was allied to a group of inner-city organisers who lived closer to the University and were based in North and West Melbourne. This group centred around Ruth and Maurie Crow and their North Melbourne Association – the Crows were a couple with long histories of urban organising in trade unions and welfare – and the much younger child-care organiser Winsome McCaughey, who also lived in North Melbourne14. With McCaughey and fellow architect Lecki Ord, Deborah made spaces and resources for child care. The 1972 Act would provide funds for non-profit organisations to finance child care for working and ill parents. This was a formal acknowledgement that women were also workers within the city, challenging the gender segregation of suburb and central business district[27. See the early study by Dolores Hayden, “What Would a Non-Sexist City Be Like? Speculations on Housing, Urban Design, and Human Work” in Catherine R. Stimpson et al., ed., Women and the American City (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1981), 167–184. The essays were republished from a special 1980 issue of the feminist journal Signs.].

Despite the funds, many child care organisations had limited resources, and buildings were generally “repurposed”15. The 1974 Melbourne resource manual on Community Child Care included an architectural plan, perhaps attributable to White, of a conversion of three terrace houses into a child care centre. Women activists followed patterns of earlier feminist generations in building on existing institutions, in this case the university and churches, to establish their new organisations within properties owned by older institutions. White reused university terrace houses for child care facilities and converted the vacant halls and church buildings belonging to the Presbyterian Church. The Church, in turn, lent support for the Community Child Care book.

In 1974, McCaughey, White and others established the Wimble Street Child Care Co-operative in Parkville in a neighbourhood adjacent to North Melbourne and close to the University of Melbourne. At 18 Wimble Street, there was a large federation-era house with a dairy at the rear. By the mid-1970s, the suburb of North Melbourne contained large public housing estates, areas of urban demolition and abandonment, and remnant industries and industrial properties. A vast set of nineteenth-century open pavilions housed the Victoria market on the urban periphery of North Melbourne and dairies dotted the North Melbourne landscape. These industrial facilities for processing the agricultural product brought from the hinterland would be increasingly demolished and converted through the 1970s and 1980s. This inner-city landscape was in transition. In 1973 and 1974, Deborah White was busy with a lecturing job at the University of Melbourne and the full-time care of her young child; the Wimble Street renovation and extension was co-designed with Greg Burgess, a former student of Deborah White’s, who she had taught in the 1960s at the University of Melbourne. Burgess became an internationally and nationally acclaimed architect. His practice developed a strong specialisation in community facilities and built admirably co-operative relationships with community clients.

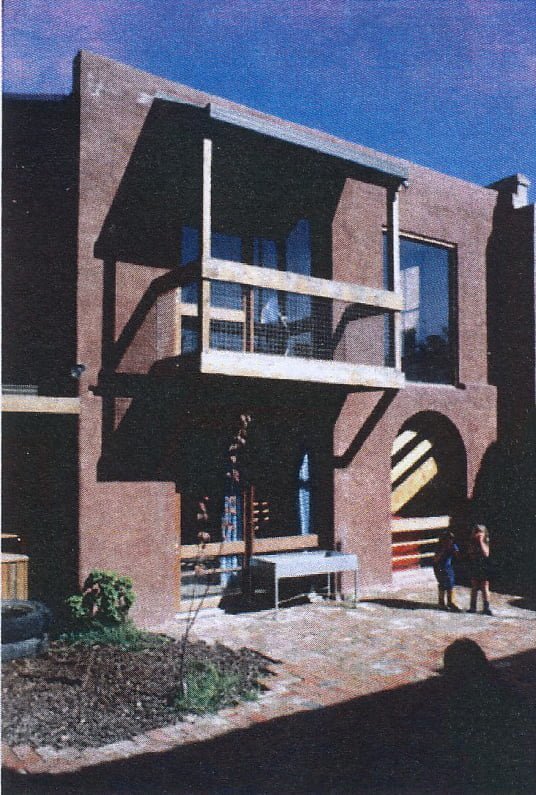

The rear facade of the Wimble Street extension. Photo: Greg Burgess.

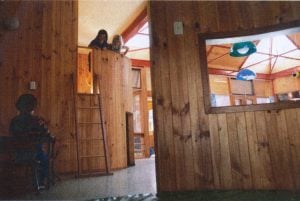

In line with the growing shift to human-environment relations, the new Wimble Street extension was conceptualised as an environment planned for children’s play. The involvement of the first director, a Montessori teacher, was crucial in both the design and functioning of the centre[29. The Montessori approach involved multi-age groupings to foster peer learning, and the guided choice of activity in a large space prepared by the teacher with learning materials meticulously arranged and available for use, thus developing independence, freedom within limits, and a sense of order. The child, through individual choice, makes use of what the environment offers, with ‘hands-off’ teacher support and/or guidance.]. The very large play-area ran counter to the received vision of the time, which assumed that children would be effectively ‘segregated’ by age, and tended to see large spaces as intimidating for small children. The early 1970s was the fulcrum of a post-war push theorising “play” as a critical element in early childhood development. In 1973, researcher Arvid Bengtsson declared the child’s right to play and explained the importance of children’s play, in which children acted out the world around them16. The disciplines of architecture and performance interacted. The purpose-designed environment was conceived as a constructed space and as a framework: a stage set for play actions17. An observational methodology was incorporated within the design guidelines provided by the Community Child Care resources manual. The 1974 plan of the converted terrace houses in the Community Child Care source book includes a window in the central reception area from which “a parent can watch the children playing”. A large proportion of indoor and outdoor space was devoted to play landscapes. Situating play as a form of performance, and conceiving of space as a framework for stimulating performance, links these designs to a broader architectural concern with space as theatre across the 1970s[32. The obvious local comparison is with the work of Edmond and Corrigan but research and studios conducted at the AA, notably by Bernard Tschumi and others, provide another example of this interest. On the former, see Richard Munday, “Passion in the Suburbs”, Architecture Australia, February/March 1977, 52; and Sandra Kaji O’Grady, “The London Conceptualists: Architecture and Performance in the 1970s”, Journal of Architectural Education, 61, 4, 2008: 43–51.].

The Wimble Street extension was designed for children’s play. Photo: Greg Burgess.

Organised day-care aimed to supplement the informal arrangements that many inner-city parents used and to provide stability, since informal day-care could involve frequent changes and disruptions. Many of the reports paid specific attention to the needs of immigrant families who sometimes lacked extended family networks. Having spent a year in Italy in the mid-1960s, White was fluent in Italian. She taught English at the Istituto Italiano di Cultura and through these relationships became the co-designer for the Italo-Australian Foundation Childcare Centre in Carlton in 1975. Once again, White collaborated on the design with Greg Burgess’s office. Organisers within the Italo-Australian Education Foundation had a strong cultural mandate for the project, using funds raised by the Italian Community Charity Quest18. A child care centre staffed by native speakers was important for maintenance of cultural identity. Living language use was key for both parents and children. The design uses a sweeping brick Corbusian wall as a screen to unite two Victorian terrace houses and an adjoining block19. Cut outs in the wall plane reveal the remnant houses; the south portico frames the terrace house behind, and a circular viewing window over the northern portico entry exposes the interior mezzanine. Once more, the interior is organised around a play landscape. The internal walls of the existing terraces were demolished and the new timber and post structural system allowed the creation of multiple mezzanine levels of great variety.

The Italo-Australian Foundation Childcare Centre in Carlton. Photo: Greg Burgess.

In 1975, the Whitlam government fell, but many of its concerns with community and funding for community ventures, housing and multiculturalism were continued by the incoming conservative government. Community groups and new facilities thrived during the 1980s. White’s urban landscape of social movements, local organisers, family, neighbourhood, and new community organisations (not institutions) and marginalised groups presented a different course of action for architects within the city. The demands articulated in her “Women and Architecture” essay presented a radical challenge to architectural values by asserting community as the concern for architecture, and dismissing “the heroic myth of the gentleman architect” who produces “great monuments at the behest of an admiring client”8. In recent years, these disciplinary fissures have reignited20. The theme for the 2016 London Festival of Architecture was “Constructing Community”. This essay recovers 1970s community building histories in order to construct an archive and context for the current return to community as a focus of architectural action21.

Architecture’s commodity value (its bronze medal status) was explicitly called into question in the period from 1975 to 1976. Deborah White’s critical terms were organised by ideas of gender, resources and community. Geography was critical to the communal endeavour, as the city was framed around the scale of the neighbourhood. Community was not a pre-assumed organic entity but a structure of connection, formed through physical proximity and shaped in organised spaces of encounter and exchange. Local child care centres provided part of the social environment for children where they would act out the world around them, including their identity within a broader community. The centres also provided parents with a locus for sharing and exchanging resources and the emotional structure of community “knowing and being known, caring and being cared for”. The North Melbourne Association summoned the metaphor of “community fabric” “torn to shreds” to describe transformations within the late modern city. They countered the alienation of the modern city (White’s “hostile environment”, Corrigan’s “brute steel”) with a communal ideal, thus continuing a theme introduced by social critics of the nineteenth-century industrial city22.

In the City

White’s story takes shape within geographies of urban activism, as women architects and others “designed” new sorts of places in the late modern city. The city is a cultural landscape that can be mapped through a “network of relationships”. The story of transforming the city is a story of relationships, friendships and urban networks. Setting the story in the city unravels the complex links between architecture, women’s activism and other social movements in which White was engaged: from urban environmentalism, to sustainable energy campaigns, to planning protests. Her practices and those of her child care allies were a form of “community feminism”: a type of activism organised through social movements and voluntary associations in local communities[39. Nupur Chaudhuri, Sherry J. Katz and Mary Elizabeth Perry, eds, Contesting Archives: finding women in the sources (Chicago, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2010), viii.]. Key books from architectural critics such as Charles Jencks and Malcolm MacEwan are often cited as documents in the growing 1970s “crisis” around architecture and late modernism, but as this brief history testifies, different archival material can link the post-modern architectural turn with activist actions and urban contests.

This is an edited version of an essay originally published as part of “Gold”, the 2016 Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians of Australia and New Zealand.

Karen Burns is a member of the Parlour collective. She is a researcher in the Melbourne School of Design at the University of Melbourne. With Lori Brown she is co-editing The Bloomsbury Global Encyclopaedia of Women in Architecture, 1960-2015 (forthcoming 2021). Her research on Deborah White is part of an oral history project on second wave feminism and Australian architecture, which she is working on very slowly. She would love to hear from anyone who might be able to contribute stories, images and biographies to this project.

- The Royal Victorian Architecture Medal; see also Judging Architecture: issues, divisions, triumphs, Victorian Architecture Awards 1929–2003, ed. Philip Goad (Melbourne: Royal Australian Institute of Architects, 2003).[↩]

- Corrigan, “Bronze Medal”, 34.[↩]

- Deborah White, “Women and Architecture: A personal observation”, Meanjin Quarterly, Summer 34, 4 (December 1975): 399–404.[↩]

- White graduated from the University of Melbourne in 1962. She is of the same “architectural generation” as Daryl Jackson and Evan Walker. After returning from Italy, she worked in Robin Boyd’s office, run by the powerhouse Berenice Harris.[↩]

- White, “Women and Architecture”, 404.[↩]

- Corrigan, “Bronze Medal”, 41.[↩][↩]

- Corrigan, “Bronze Medal”, 41; White, “Women and Architecture”, 402–403.[↩]

- White, “Women and Architecture”, 403.[↩][↩]

- See Renate Howe, David Nichols and Graeme Davison, Trendyville: The Battle for Australia’s Inner Cities (Clayton: Monash University Publishing, 2014); and Meredith Burgmann and Verity Burgmann, Green Bans, Red Union: Environmental Activism and the New South Wales Builders Labourers Federation (Sydney: UNSW Press, 1998). For more on earlier 1950s protest, see David Nichols, “Boiling in Anger: Activist Local Newspapers of the 1960s and 1970s”, History Australia, 2, no.2, 2005: 1–16; and James Miller, The Representation of Place: Urban Planning and Protest in France and Great Britain 1950–1980 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003).[↩]

- North and West Melbourne Neighbourhood Centre, Discovering Our District: “When Bull-dozing Boomed” (Fitzroy, Vic.: Sybylla Press, 1985), 17.[↩]

- Community Child Care Association, What is Community Childcare? (Fitzroy, Vic.: Community Child Care Association, ca.1979/1980), 2.[↩]

- Philippe Aries, Centuries of Childhood: A Social History of Family Life, trans. Robert Baldick (New York: Vintage, 1962).[↩]

- Deborah White, interview with the author, December 2015.[↩]

- The North Melbourne Association produced a submission in June 1972 to “The Consultation Council on Pre-School Child Development”, based on detailed questionnaires distributed, filled out and analysed from within the local community. Pamphlet, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne.[↩]

- The repurposing of buildings can be traced back into the nineteenth century. See Marta Gutman, A City for Children: Women, Architecture and the Charitable Landscapes of Oakland, 1850–1950 (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2014).[↩]

- See Arvid Bengtsson, Environmental Planning for Children’s Play (London: Crosby Lockwood Staples, 1973).[↩]

- See the bibliography of reading resources – including Bengtsson listed in the final pages of the 1977 edition of Community Child Care, ed. Winsome McCaughey.[↩]

- James Gobbo, Something to Declare (Melbourne: The Miegunyah Press, 2010), 132.[↩]

- Jennifer Taylor, Australian Architecture Since 1960 (Sydney: Law Book Company, 1986), 160.[↩]

- See Maren Harnack et al, ed., Community Spaces: conception, appropriation, identities (Berlin: Technical University, 2015). For an important critique of the binary opposition community/architecture, see Jeremy Till, “Architecture of the Impure Community” in Occupations of Architecture, ed. Jonathan Hill (London: Routledge, 1998): 61–75.[↩]

- Brian Donnelly, “Locating Graphic Design History in Canada”, Journal of Design History, 19, 4, Winter 2006: 291.[↩]

- Notably Augustus Welby Pugin and John Ruskin. See Edward Timms and David Kelley, eds., Unreal City: urban experience in modern European literature and art (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1985).[↩]