Kerstin Thompson reviews US historian and writer Despina Stratigakos’s latest book Where are the Women Architects?

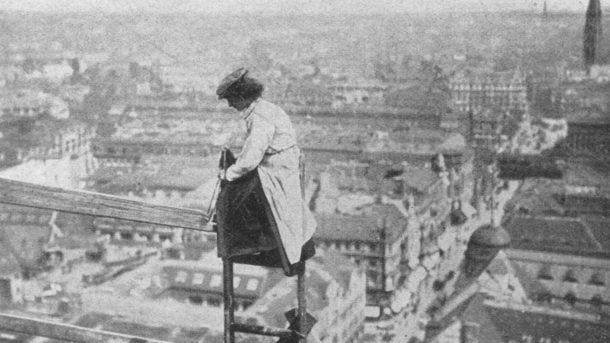

A female builder shows off her daring to the press while repairing the roof of Berlin’s City Hall in 1910. Illustrierte Frauenzeitung 38.

Picture this: a woman suspended on a swinging beam, nine storeys up, being interviewed about being an architect. This vision of daring and ambition is in the year 1911 and the woman is Fay Kellogg, a trailblazer keen to impress upon her peers and the public alike that women in her profession are capable of far more than ‘building closets’.

Reconcile that gesture with this fact: In 2015, when UK publication Architects Journal asked its readers whether they would encourage a woman to enter the profession only half said yes. Despina Stratigakos’s brief but to-the-point book replies to this apparent impasse by posing the question articulated in its title. In doing so it offers moments of both despair and delight in rendering the fit and place of women within the practice and culture of architecture.

Stratigakos’s analysis falls roughly in three parts. The first is where to put them. She quotes Kellogg: ‘I don’t think a woman architect ought to be satisfied with small pieces, but launch out into business buildings’. It’s an ambition that contrasts with the prevailing view of the time that women should remain aligned with the domestic sphere. As Jean Wehrheim informed The Chicago Tribune in 1966: ‘We have a natural inclination for designing homes … men prefer big projects, like offices and public buildings, but I know what I am doing when it comes to designing a kitchen.’ I’m with Ada Louise Huxtable when she laments that this ‘pious claptrap [about] women’s greater domestic sensibility’ only serves to manacle women’s talents and prospects.

Stratigakos states that her agenda is ‘less to chronicle women’s entry into the profession than to track an unfinished dialogue that has haunted architecture – in a cycle of acknowledging and then abandoning its gender issues – for a very long time.’ This, she says, is to strengthen a third wave of feminism in architecture, which follows on from the first wave of the nineteenth century and the second wave of the early 1970s. Because, as evidenced by this book with its distinctly American focus, and closer-to-home research by Australian-based Parlour, this long-lived debate has failed to fundamentally reshape who practises architecture and how.

So where do all the female architects go? Each chapter tackles the persistent phenomena of why, if 60% of university graduates are female (in the US at least) only 20% of registered architects are women. Stratigakos analyses research on attrition rates and highlights a potent mix of structural problems: industry conditions, sexism within the ranks of management, the implied ‘character’ of the profession as masculine, lack of female role models and mentors, and the problem of history repeating itself, thus quarantining the architectural cannon against traditional outsiders.

While the undesirable mix of low pay and long hours endemic to the current industry is experienced by both genders – hardly compatible with parenting and life balance – it’s exacerbated for women by the 20% pay gap. Beyond this, the inbuilt sexism of the industry is manifest not in the lazy cliché of the wolf whistle on-site but within the walls of the white-collar office. Here, it is disguised in more passive forms that subtly define and constrain a woman’s place within the production of buildings, the types of projects and kinds of roles supposedly ‘most fitting’ for them.

This leads Stratigakos to her next question: What does the architect look like? Enter Architect Barbie, a toy created by Mattel in 2011. In all her curvaceous, blonde splendour, Architect Barbie presents an image for the architect that embodies the binary opposite of Ayn Rand’s figure of Howard Roark as the twentieth-century architect archetype – male, bullish, determined, resolute, didactic, unwavering in the face of client desires. The chapter on Barbie outlines how, not surprisingly, the doll has provoked inter-generational anxiety, particularly amongst feminists. ‘Barbie … has the power to make things seem natural to little girls … ultimately she is for kids, not adults, and it is the politics of the sandbox that I hope to influence … when little girls claim hard hats and construction sites as just another part of their everyday world.’ I’ll side with those who see this initiative as one of empowerment and resistance not oppression, namely for its capacity to speak to and through the next generation via the everyday world of play, to ‘learn how to shape and control their own spaces’.

Stratigakos’s book places great emphasis on the issue of recognition and argues that new communication technologies and social media promise a means of ensuring the stories of women in architecture can be told, rectifying their long pattern of omission from the writing of history. If old modes of recognition, such as the monograph, were predisposed to documenting the contributions of single authors, then new modes such as Wikipedia and other more dynamic, nimble online forums can begin to advocate for women in architecture in new ways.

She examines the pros and cons of initiatives such as women-only awards and their role in compensating for the problematic faith in a meritocracy. Of note here is how few women have received the most prestigious of trophies for their contribution to architecture. And when they have, like Zaha Hadid (the only woman to receive the Pritzker in her own right), they are lampooned for details of their personal life and required to take the hit for society’s reservations around ambition and self-promotion as an ‘unattractive female trait’.

While some questions go unanswered – why, for example, the retention of women graduates in architecture still lags behind other former male bastions such as law and medicine – Stratigakos’s provocations render this a valuable read. Perhaps in wrestling with these questions we might illuminate a path towards more sustainable forms of practice, for all its practitioners – women or men.

And to those who responded to the Architects Journal’s survey in the negative, I would advocate for more optimism and wager a bet that the future skies and great heights of our cities will be occupied by many more Fay Kelloggs.

Kerstin Thompson is principal of Melbourne-based Kerstin Thompson Architects (KTA). She is also professor of design in architecture at VUW in New Zealand and an adjunct professor of architecture at RMIT University and Monash University.

Note: A slightly shorter version of this review was first published in The Age and Fairfax Media, and is republished here with permission.