Warwick Mihaly reflects on architecture and fatherhood.

I am an architect and I am a dad.

I’m lots of other things as well – a husband, a small business owner, a writer, a teacher, a runner – but these two things (together with being a husband) represent the biggest and most important part of me. They demand the lion’s share of my waking life and I dedicate to them the lion’s share of my passions and energy.

For many parents, both men and women, the separation of these roles is reinforced by any number of influences: the physical act of leaving one’s home to go to work; the contrasting mental spaces required to work and to parent; fossilised attitudes within the workplace; even the desire to safeguard the efficiency of work and preciousness of family. The latter was certainly the case for my parents, who put great effort while I was growing up into protecting the bookends of the day.

Deservedly, this subject has received a lot of recent attention in lecture, institutional and media circles. The gender discussion is multifaceted, but revolves predominantly around equity, work/life balance and family. Thanks to excellent research conducted by Parlour, we know that women disappear from the profession as they get older.[1. Around 45% of architects in their twenties are women. This number declines to less than 10% for architects over 55 years of age. Statistics sourced from Gill Matthewson; The numbers so far; Parlour; March 2012.] We know that disparity between the career progression of men and women still exists. And we know that long hours and poor pay remain a systemic problem within the industry, conditions that prohibit the balance of work and family.

But this is not my experience.

For me, the presence of women in the workplace, together with a flexible, family-friendly approach to working hours are the norm. After graduating, I worked at Perkins Architects where half of the twelve architecture staff were women, where part-time work for returning mothers was encouraged, and where the day started at nine and finished at six. Since establishing Mihaly Slocombe in 2010 with my wife, Erica Slocombe, these conditions have endured. We work from home, enjoy flexible working hours, wrap up by six, and our son, Oscar, is an important (if sometimes destructive) part of the studio environment.

This is not to say that we are world’s best practice. We don’t have an official gender or family policy. Plenty of the choices that have lead to our current work / life balance have been unconscious. And our parenting roles are in many ways based on traditional gender divisions. We are not driven by a fervour for gender equity, we just live and work in a fluid way that feels right.

I wonder if this is a commonplace arrangement? Since so many architects at some point start their own practice, surely my experience is not unique. Surely there are other archidads out there sharing the parenting load… Which is why I’m writing this article. Amidst all of the wonderful energy devoted to revealing and correcting the gender imbalance and poor working conditions that we know persist in our profession, the role of working men in parenting seems to be a less popular subject. While the picture we have of working mothers is highly detailed, the one of working fathers is blurry at best.[2. I refer here to the general tone of the gender equity discussion. Since I am by no means an expert, I may be entirely wrong here. Please feel free to correct me if I am.]

I’d like to share my story in the hope that it provides some (tiny) measure of balance to the gender discussion. There is no doubt that the old boys club, unconscious bias and the glass ceiling are men’s shame to bear, but when I reflect on my dual identities as architect and dad, or should I say, co-identities, I am struck by how unlike the traditional caricature of male architects my life is.

Location, location, location

More than anything, this distinction is enabled by the location of the Mihaly Slocombe studio in our spare bedroom. Working from home means work and family flow into one another: I am around my family, and my family are around my work, all the time. Design presentations, emails and piles of drawings overlap with play, songs and piles of toys. There is a shifting but ever-present colony of Matchbox cars in every corner of our house, my desk included.

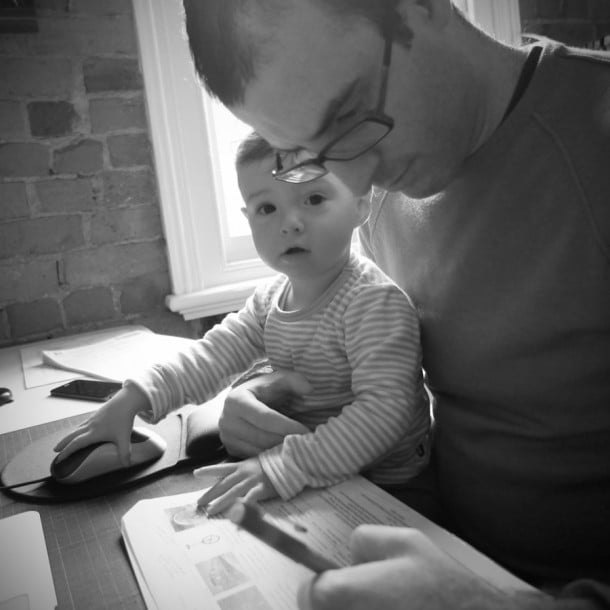

My day would not be complete without at least one stint of working with Daddy time, memorable sessions involving Oscar perched on my lap while he navigates my iPhone with unnerving aptitude and I try valiantly to tap away at my keyboard around him. Meetings and deadlines are scheduled around nap times, dance class and nanny days. Making any decision in our work life means negotiating the needs of our family life, and vice versa.

I even muse sometimes what influence this will have on Jake, our graduate architect. He takes part in the rituals of family lunch most days; he gets to enjoy Oscar’s regular visits to our studio space and interchangeable demands for John Lennon’s Give Peace a Chance and Craig Smith’s timeless The Wonky Donkey; he arrives in the morning to tales of sleep deprivation; he has watched Oscar grow from a baby into a toddler.

Blurring boundaries

While working from home began as a decision to reduce our operating costs, it has evolved into an essential ingredient in the way we do business. This might strike many as highly counterproductive. And it’s true that a different office environment might facilitate greater profitability (as might slogging away at work 10 hours a day, 7 days a week). But in Oscar’s three years, I’ve never found the blurring of my identities to be a problem.

The practice of architecture has always expanded and contracted to fill the gaps in my life. All the way back to my primary school years, sketching houses was a weekend hobby. I undertook my first project commission while studying at university, and my second while working four days a week at Perkins. As a dad, architecture continues to bend and sway, to take place when it can and must.

I recognise this situation won’t last. Erica, Jake and I work 10 full-time-equivalent days between us, some of which overlap with us all working together. Our spare bedroom studio is very comfortable for two, but the third is challenging. Adding even one additional staff member would be impossible. But when a career first takes shape as a primary school hobby, even the difficult bits are imbued with a lustre of ease. I’m incredibly lucky to feel like this, I know, and recognise that for vast swathes of Australia, work is a chore. But for me, it’s just not. I love my family. I love architecture. While I still can, why in the world would I want to keep them separate?

Shared decision making

To use an old (somewhat gender-stereotypical) saying, it’s hard to say who in our family wears the pants. The same goes for our practice. As the primary carer, Erica is the expert on Oscar and so drives most decisions concerning him. As the primary businessperson, I drive most decisions concerning Mihaly Slocombe. But we are fortunate to enjoy both a work and life partnership where neither of us makes those decisions independently. The pants therefore are either large enough to fit us both, or we hop about wearing one leg each.

Ownership of our projects is also shared, as is any sense of individual authorship. This has only become more evident since Jake came on board two years ago, and his critical design input through modelling, detailing and documentation have come to reshape our design process.

Is this sharing of responsibilities rare or is it the norm? I’ve never canvassed opinion amongst either my friends or work colleagues, though it’s likely there exists a whole spectrum of structures. I do know it makes me uncomfortable watching Mad Men’s Donald Draper make executive decisions for his family. Perhaps it should be the norm. It is no coincidence that Parlour considers issues of gender equity as the canary in the coalmine for the whole architecture profession, women and men inclusive. We’re all in this together.

Future decisions

Writing this article has inspired me to reconsider my work and life ambitions. With a new baby on the way, and all the attendant furniture that will inevitably accompany her, the idea of keeping our studio at home has become more tenuous. But it’s an arrangement I hope we can retain, at least until Oscar and his baby sister head off to school, as it allows me to be the sort of parent I want to be. I like being around, listening all day to the sounds of Oscar’s play even if I’m not directly part of it. I like the zero commute time, the morning hustle to get the house ready for its use as a studio, and then the evening hustle to finish off work in time for dinner at 6pm.

When Erica returns to being a full-time mum next year, having our studio at home will also enable her to remain connected to the work of the architecture practice that bears her name. Just as I am around Oscar all day, she will be around our work all day. Quick questions can be fielded, clients can be greeted, progress discussions can be had over lunch.

When I think about it, isn’t this what the entire gender discussion boils down to? How can we, as individuals living in a contemporary, egalitarian society, live our lives so the parts are in balance with one another? Working long hours sucks. Spending evenings locked up in the office sucks. Working the right amount to contribute meaningfully to the broader community while still dedicating the right amount of time to my family feels great.

I like my life.

Note: Parlour is pleased to co-publish this article, which first appeared on the Mihaly Slocombe blog Panfilocastaldi.

1 comments

Nicole Kirby says:

Dec 29, 2014

It’s great to be able to read article like this! As a student architect, coming into my third year, it is refreshing to hear that my career can be balanced with my general life and I won’t have to sacrifice the things I love and the people I love. While you’re studying, it becomes very disheartening to hear your fellow peers complain about the negatives of the career they are heading into, i.e low pay, long working hours. Unfortunately I do see this as something already obvious in the conditions of my university work. I know if am definitely naïve in my aspiration but reading articles, such as this excellent one Warwick Mihaly, I feel inspired to pursue a career that allows balance in all aspects of my life.