What is good design? Historically, our perception of design has tended towards tangible outputs such as artefacts, physical systems and buildings. Yet this singular focus on product can lead to unintended consequences detrimental to people and planet. Authors of Designing Tomorrow, Martin Tomitsch and Steve Baty discuss how we can harness designer’s skill sets towards more long-term and system-wide perspectives. Rather than solely focusing on physical outcomes that can contribute to planetary problems, designers can be part of the solution in the improvement of livelihoods and a safer planet.

As the famous Eames quote goes, “The details are not details, they make the product”. This observation equally applies to designing physical structures, built environments, digital interactions, and services. It’s the details that make or break the experience.

But while focusing on the details, it is important to also keep the bigger picture in mind. When it comes to better briefing for design, the details make the outputs; the outcomes are shaped by the big-picture considerations. An output might take the form of a building or a website. The outcome is the impact that emerges from putting the building or website into the world.

We unpack this challenge in the opening chapter of our book Designing Tomorrow, calling out the limits of good design. As we explain in the book:

There is nothing wrong with good design. It can solve problems, give delight, and inspire beautiful thoughts and deeds. But as futurist Bruce Sterling says, ‘good design doesn’t necessarily make our world better’. Whether you are a designer or work for an organisation that designs things, it’s time to realise that good design is no longer enough. This is not, of course, a call for bad design. As Sterling goes on to point out, ‘bad design very commonly makes [the world] worse’.

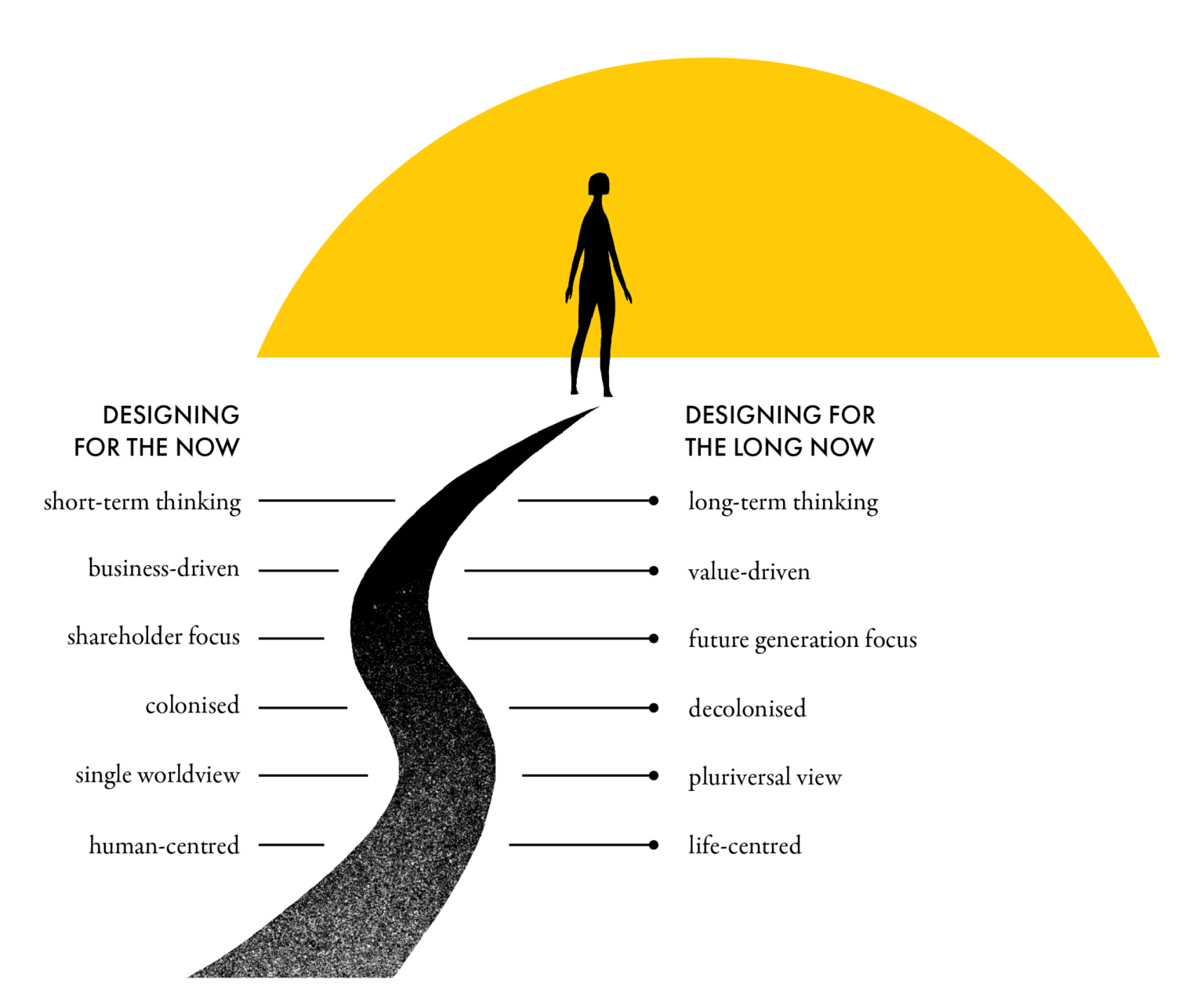

The state of the world and design’s contribution to where we find ourselves today calls for a shift in how we approach design. A shift from prioritising outputs to considering outcomes, from human-centred to life-centred design, from product to systems thinking.

It’s time to move beyond iterating and testing things in quick cycles. Especially when it comes to digital products, experiences and services, this approach – underpinned by the global success of the design thinking movement – imbues a Silicon Valley-esque sentiment. Tech companies like Meta, Uber and Airbnb built their empires on this kind of thinking. They failed to consider or, in some cases, deliberately chose to neglect the unintended consequences of the design decisions they made along the way. Uber, for example, intentionally set out to bypass regulations and undermine the economic foundations of taxi companies.

Instead of fast, intuitive thinking and subjective judgement, addressing the global challenges of our time requires actions based on slow, intentional thinking and deliberate decision-making. We need to stop designing things as though they exist within a closed system and instead recognise the reality of the interconnectedness of our modern, techno-social systems.

The short-sighted, siloed decisions organisations around the world continue to make today have an indisputable global-scale impact on the environment, communities, and future generations. If we continue to design things that push us beyond the planetary boundaries, we are essentially borrowing natural capital from future generations, and leaving them a wasteland in its place. To strategically drive change in organisations, we must realise that our role as designers and decision-makers goes beyond merely designing ‘things’. What we help to create has the power to influence the impact organisations bequeath the planet.

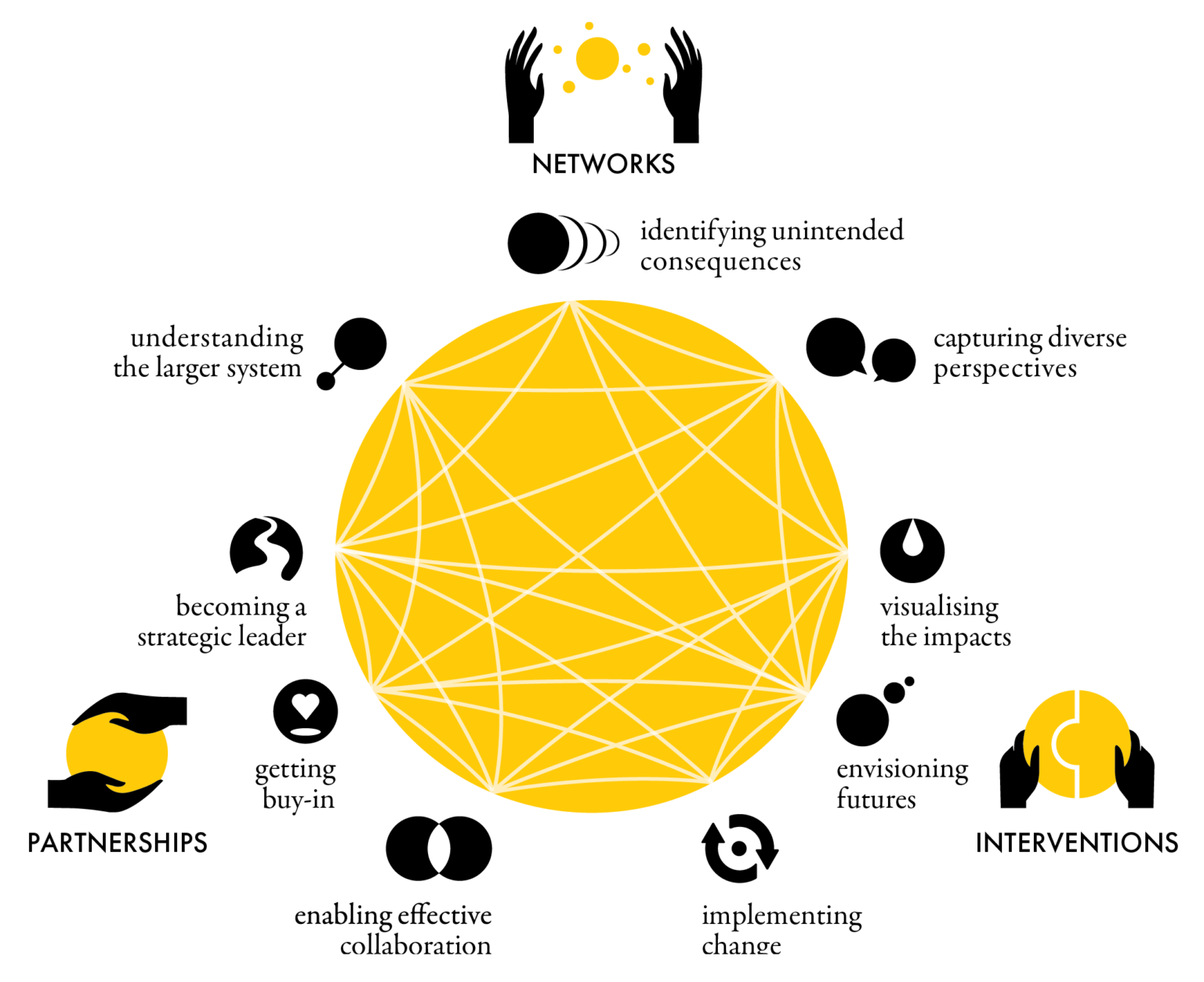

Designing Tomorrow sets out a framework for designers and decision-makers to achieve this strategic change by invoking three pillars: networks, interventions and partnerships. The first pillar, networks, provides the tools and strategies to systematically map out the multi-scale challenges and opportunities, and to understand the unintended consequences of design decisions.

The second pillar, interventions, involves turning those opportunities into change, one step at a time. Studies of non-violent protests show it only takes 3.5 percent of the population to start a movement. By embedding the strategic design tactics into the work we do, we contribute to achieving the threshold for positive change.

Through activating the third pillar, partnerships, we can take this change even further and make sure it is sustained over time.

Good design is no longer enough. But this doesn’t mean that we have to unlearn everything from our past. We can use our design skills and ability to influence decisions to help us consider the larger system and highlight potential unintended consequences.

Having contributed to the problems our world faces today provides designers and decision-makers with perspective as well as a responsibility to change what we do. We can become part of the solution.

Martin Tomitsch is a Professor and Head of the Transdisciplinary School at the University of Technology Sydney and a founding member of the Life-centred Design Collective. Martin’s other books include Making Cities Smarter and Design Think Make Break Repeat.

Steve Baty is a strategic designer with over 25 years experience as a business founder, keynote speaker, awards judge, Interaction Design Association (IxDA) president, conference organiser, and UX Book Club founder. Steve is co-founder of both Meld Studios and UX Australia.

This article is part of a series of guest articles on the Integrative Briefing for Better Design website, which covers themes relating to integrative briefing and design for transformative change. If you would like to contribute a 500-word guest article to this ongoing discussion, please email Fiona Young.