Renowned UK writer, researcher, educator and unapologetic activist Jos Boys takes us on a journey from Covent Garden squatting to Matrix, from academic life to tearing down ableist stereotypes with The DisOrdinary Architecture Project.

Discovering architecture

I fell into architecture completely accidentally. I wanted to be a photographer, but it was the 1970s and I was told that I couldn’t do that. There were lots of reasons – girls shouldn’t go into a trade, it was unseemly, the cameras were too heavy… But architecture was fine. Though entirely male-dominated at the time, it was a profession, so for my school it was a more acceptable option for me. It didn’t occur to me to argue so I ended up at The Bartlett School of Architecture UCL, which was quite a renowned school, even then.

So, here I was, a kid up from South London with a family who didn’t really know what architecture was. At the time the Bartlett was quite hippy. It was part of the Slade art school, so there was paint all over the floor, the students served us all lentil stew, and I thought it was brilliant.

Education

I shipped up into architecture without any of those organised reasons that people have for choosing the profession – and then had this odd combination of really loving it and feeling like a misfit. But architecture education at that time was very much about being taught to be a modernist – and there was an assumption that this was really obvious. This is just what you did. Quite a large percentage of people were able to just absorb the way that architecture was taught and the things that mattered, which all related to modernism. You started from first principles and, somehow, you came out with white concrete buildings. For me, it didn’t sit well. There was quite a lot of struggle. It endlessly raised questions for me. I wondered, “Why are we doing that? Why aren’t we doing this?”

At the same time, there were some brilliant things about the course. The first thing we were taught to do was to douse for water under the ground, using a forked stick. We learnt about ley lines and sacred geometry. One of my first teachers there was an American who wore very pale leather trousers and went off halfway through our first year to dive for Atlantis in the Bermuda Triangle. We could choose to study Marxist planning rather than Structures. We looked at planning and urban development in really interesting ways. The undergraduate course resulted in a degree in Architecture, Planning, Building and Environmental Studies, with the aim of giving you all sorts of options – not just a conventional career as an architect.

Many people left that course and went and did other things. Lots of people went into building or they developed their own design / build practice. Others went into briefing organisations for development. One of my friends ended up at the World Bank. So, the idea that you were doing this degree to become an architect wasn’t really the norm.

Architectural journalism

At university, I had to write an academic essay about Marxism and the environmental crisis, and one of my tutors had remarked that I’d make a good journalist (which was intended as a criticism really). So, I went and got a job as a cub reporter at a trade paper called Building Design. The paper did lots of news stories, so I was able to go and interview people about what was going on in the industry. The people running the paper had been in traditional newspaper journalism, so they were really good at providing that kind of apprenticeship.

At first it was terrifying. I used to go and cry in the toilet. But they were really good at teaching me how to write. I learnt so much. I was there for two or three years. And then out of that, I ended up freelancing for another four or five years as a journalist. I wrote feminist material for The Architects Journal and I wrote architectural articles for Marxism Today – but I also did some straight up and down architectural journalism and criticism.

Community action

That whole period in London was very different from what it’s like today. In the 1970s and 80s, London was really very derelict, which is hard to imagine now. There were lots of vacant buildings and plans to tear everything down. The government wanted to drive motorways through the centre of London. A lot of high-rise office buildings were being built, which were entirely for the capital value, so the offices were empty (for example, Centre Point at one end of Tottenham Court Road, and Euston Tower at the other; both right next door to the university campus). Many Bartlett students got very involved in campaigning, working on schemes around community action. People were squatting and working with community groups. It was just what everybody did.

Some of these community actions were really powerful. Parts of the London South Bank have public housing on them today that would have been massive areas of office blocks if the developers had their way. So, community activism had a big effect. It was a real movement.

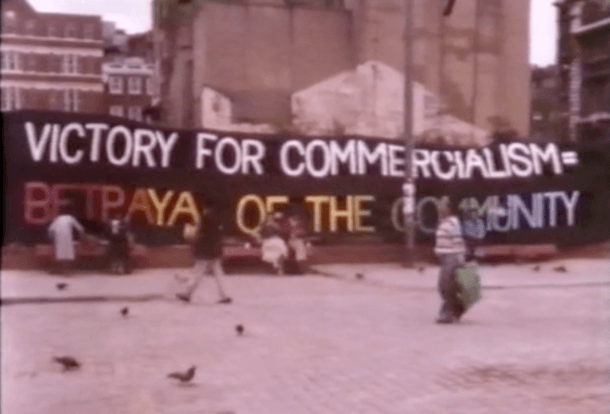

For instance, there were plans by the Greater London Council in the late 1960s to redevelop the old wholesale fruit and vegetable market in Covent Garden, in the West End. The plan was for demolition, with a new road system and pedestrian walkways driven through the middle of the area. Through the protest actions of local people, with support from radical planners and architects (particularly from the Architectural Association), this redevelopment was prevented.

Archive images from The Battle for Covent Garden video, made with digital:works.

As architectural students, we ended up living in a huge squat with a gang of friends, hippies and homeless people as part of saving the area. We lived in these beautiful eighteenth century Georgian terraces that were going to be replaced with high-rise offices – about 60 people squatted in six five-storey houses around a corner with a huge warehouse tucked in the middle, right next to Convent Garden tube station. The properties were derelict, with wrecked toilets and a roof that had already been damaged by the developers, who hoped this would bring the whole building down. We did an amateur repair job on the roof, and climbed through windows and over roofs to use the few toilets and bathrooms. In the end, we lived there for about two years. This didn’t save the houses or warehouse – after we moved out they were replaced, but at least it was with terraces of a similar scale and look.

The work of resisting the plan over many years is an interesting story, which you can find more about on the web. Our group of architecture students only arrived towards the tail end when the original plan had been dropped, and a more community-centred Action Area Plan was being negotiated, so we were only a minor cog in a much bigger community action.

Cheap living

Living in a squat when I first started working at Building Design obviously enabled me to live on a very low salary. Then when I started freelancing I was able to rent a shared workspace part-time just nearby in one of London’s first cooperative workspaces, called 5 Dryden Street (which also had the benefit of running water, telephones etc.) At that time, local councils usually didn’t have the funds to do up older houses in poor condition, often because of government restrictions, so they would get people to come and live in properties very cheaply. The rental costs were kept very low, and in exchange the renters would keep the properties maintained and unvandalised. So, after Covent Garden a group of us – now all ex-architecture students – ended up in what was known as a legalised squat in North London, two houses knocked together with eight people sharing.

That way of living – very cheaply and in pretty seedy conditions – was a fantastic way to develop a reasonable live-work strategy, because the overheads were incredibly low. As a freelance architectural journalist, I didn’t need to be earning huge amounts of money. Rent and transport costs were low. I was mixing with a really interesting group of people and I could do what I wanted.

At one point in the early stages of the developing Matrix Feminist Design Collective, we could use a front room in these houses as an office, for free. It was really only when I had my daughter that I felt the need to stabilise my living conditions and get a proper job (as a history/theory and studio tutor), as you do.

Splinter groups

The New Architecture Movement (NAM), which was founded in London in 1975, centrally aimed to unionise architectural practice, but also to criticise conventional notions of architectural professionalism. NAM produced lots of interesting work mainly through its magazine SLATE, but it also produced lots of splinter groups. For example, I was in a group called the Novemberists (I can’t remember why), which was really interested in unravelling the relationships between critiques of architecture as a deeply unequal system of economic patronage, and issues of actual design and aesthetics. We would endlessly discuss Marxist concepts of ‘Base’ (means and relationships of production) and ‘Superstructure’ (everything else) to see where different aspects of architectural practice fitted, so we could decide if architects were or weren’t an ideological tool of capitalism (!).

Another key splinter group was women who thought that NAM was male-dominated both in its ideas and in its organisation. It is only at this stage that I got to know this group when I went to cover their conference ‘Women in Space’ for Building Design as a freelance journalist. I was still squatting in Covent Garden at this time and had a co-working space with free access to rooms for meetings, so we had a lot of meetings there. We had large groups – 40–50 women at a time. It was fantastic. However, there were women with what felt like two quite different concerns in this group.

Some really wanted to focus on improving opportunities for women in the architecture profession. Then there was what became a group of about 20 called the Women’s Design Collective, which became the basis for Matrix. This group thought there was something deeply wrong with the way architecture was run, and that practice and education needed to be done completely differently.

So, in the end, there was a split that formed two groups: one called Matrix and one called Mitra, which was set up as an architecture practice (and a lot of those women are still around doing really great architectural work).

An early poster for Matrix, when it shared space with Jos’s legalised squat.

Matrix

Matrix Feminist Design Cooperative was set up in 1980 and ran until 1996. It was founded by Frances Bradshaw, Anne Thorne, Barbara McFarlane and Susan Francis, who met as undergraduates at Newcastle University, and all continued their studies in different London Diploma schools. As I have said, via the New Architecture Movement, this also led to alliances with a wider feminist architectural network; and in Bradshaw and Francis’s case was deeply informed by training in building trades alongside women builders.

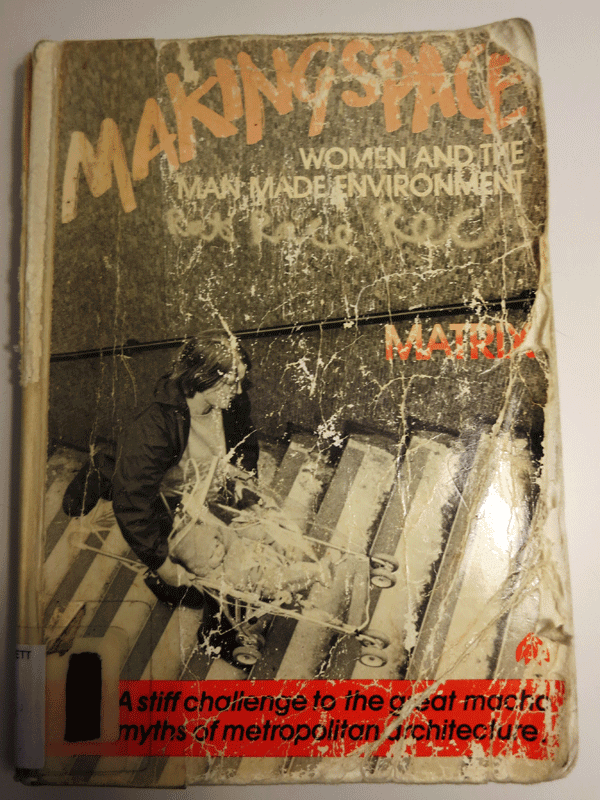

Cover of Making Space from the Bartlett architecture school library.

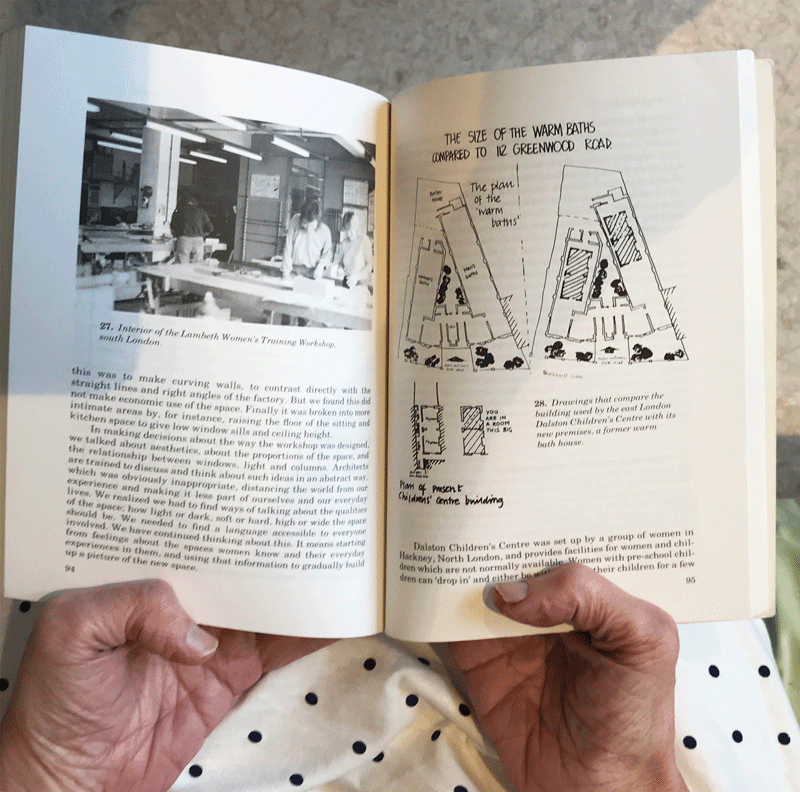

Sketch design for Dalston Children’s Centre, in the Making Space book.

There were different groups of women involved in various aspects of the initial setting up period: a ‘Women and Space’ conference group, a ‘Home Truths’ exhibition group, the design practice and a Matrix book group – which is where I was directly involved from 1980 to 1984 when the Making Space: Women and the Made-Made Environment book was published. We were brought together by a whole set of connected projects and ideas. For the book group, that was around even beginning to find a language for mapping and analysing how space and the profession were gendered.

At the time, the word sexism didn’t exist. The idea that the built environment wasn’t neutral didn’t exist as an idea. There was a belief in the mainstream that architecture was a rational profession that just did the best it could for everybody. So, through many group discussions around a kitchen table, or in people’s gardens, we tried to unpick the ways in which conventional built environment education and practice failed to engage with gender and space, or with inequalities in design, and construction processes.

This also meant exploring and implementing alternative forms of practice. There was already a lot of interest in community action and participatory methods, and there were already books on architecture without architects. There was a whole popular movement protesting state and top-down initiatives for things like road schemes and the design of public housing. We already had community technical aid centres (rather like legal aid services), which were architects providing services to community groups, usually directly in a locality through a shop. These activities were informed by feminist geographers and historians who were looking at what had been designed for women – people like Susanna Torre and Dolores Hayden in the US and Doreen Massey and Linda McDowell in the UK. So, there was feminist work to build on, although it tended to come out of geography and history, not architecture.

I never worked for the design practice, although I did help out with some funding bids and in reviewing the Building for Childcare booklet. From about 1984, when my daughter was born, I started teaching, and focused more on paid projects, such as helping to reframe Womens’ Design Service as an information service (rather than a design practice) and co-writing GLC guidance on Women and Planning with Sue Flack.

At one stage, I was invited to go to Perth to do some talks for the Ministry for Women’s Interests about feminism and women in architecture – everything from talking to an indigenous group of parents through to a huge group of planners from across the state. Many didn’t take it seriously and thought the ideas were a bit of a joke. They asked inane questions. Well, what does a feminist architecture look like then? They regarded our ideas as funny and alien. But, also, there was an idea that, maybe, we might just be able to tell them the answer. “Tell us the answer and we’ll be fine. We don’t need to do anything else. We don’t have to change at all. Just tell us what to do, so we can recognise a feminist building when we see one.” That was interesting. So often responses missed the point.

They were unable to see that feminism was challenging the very basis of architecture as an education, profession and practice; and not just offering a few ‘add-on’ adaptations that would enable the ‘boys club’ to go on in the same old ways, just feeling better about itself because it had ‘let’ a few more women in. I think that has always been a creative generator for me, trying to find persuasive ways of thinking and doing architecture differently – more equitably, and without the pretension.

A fertile ground

Looking back, I can see that it was an extremely privileged period for socially engaged work. Matrix arrived at the time that the Greater London Council (GLC) also became very progressive under Ken Livingstone. So, there was a whole patch of time where there was funding for feminist and community-based projects. The GLC women’s committee also funded the guidelines on gender and planning, as well as ones on race and planning, and there was, most importantly, funding for groups like Matrix to actively run and publish, design and complete projects.

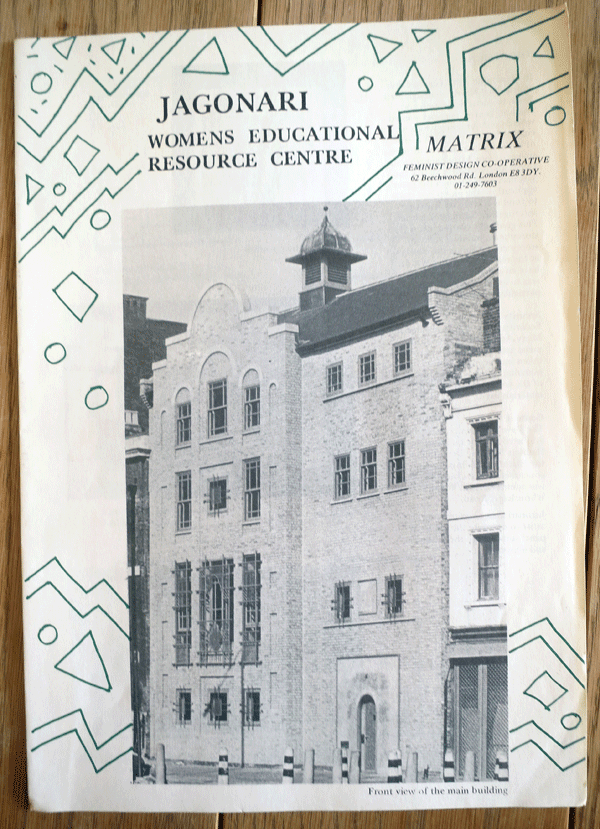

There were also community groups like Jagonari, which was an Asian women’s education and resource centre in East London. There was money for them to get a building and be involved in the design of it. So, there were opportunities to actually co-explore what a design process was like and how you did it and how you might do it differently. Jagonari was designed really, almost entirely around models, around visits to other places, around discussions with the client group, and that’s true of a lot of the other projects. Sometimes of course, Matrix projects never got built, not necessarily because there wasn’t the money, but because the groups might disintegrate or just couldn’t sustain themselves. But there was this moment through the 1980s where new kinds of community projects and innovative building types were being realised right across London and elsewhere.

Matrix promotional leaflet for the Jagonari centre.

Not a career

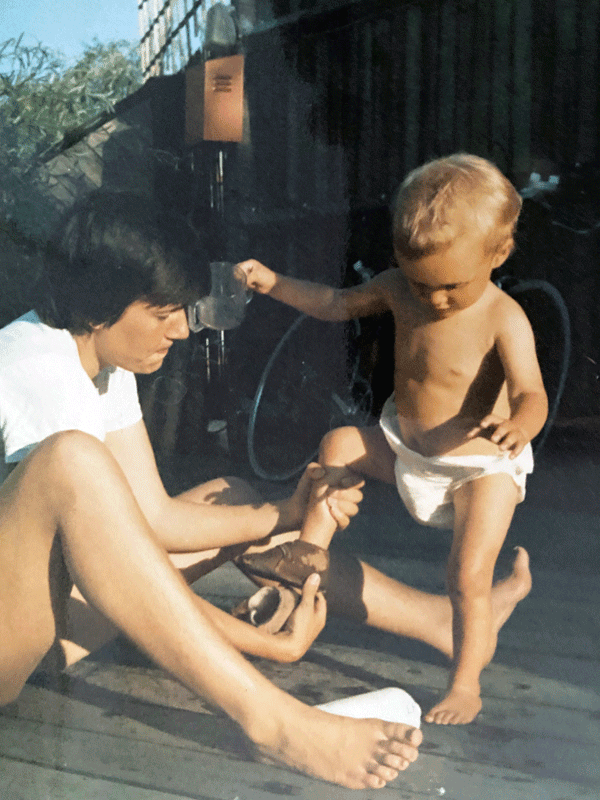

During this period, as I seem to be mentioning a lot, I still managed to have very low overheads. I was living on a boat in Central London with my daughter, because it was very cheap (she did, admittedly, fall in a couple of times). Being a single parent was fantastic, and my daughter gorgeous then and now. But she didn’t sleep much in the beginning. She wasn’t interested in sleeping, just always curious about everything and not wanting to miss out, so I was completely exhausted. I stopped working as a journalist because I could not guarantee hitting deadlines and started teaching architecture part-time at a university. At the Polytechnic of North London, they had a nursery which was free. My daughter and I made incredible friends with the nursery staff, who would also look after her, after hours, when I was working. So, that really helped. Actually, our timing was fantastically lucky, as just as my daughter turned five and went off to primary school, they started bringing in fees.

Life and times living on the canal.

I go on about the financial side because I made a choice really early on that I did not want to be forced into full-time work to pay for a mortgage and a ‘lifestyle’. So I have been able to freelance doing a range of different projects across journalism, research, teaching and consultancy for many parts of my life; often just by being on the lookout for opportunities, or generating those opportunities myself. I won’t pretend I haven’t done ‘9–5’ full-time jobs, but this is definitely the kind of work I am least suited for.

I really struggle with the word ‘career’. It’s not that I haven’t had a sense of what I want to be doing, but it’s been driven by being really interested in questions that don’t get asked around architecture, starting from when I was a student. So, how does space work in a gendered way? It’s just a really interesting question. I worked on that question for 12 years, because initially it was almost impossible to think through.

My ‘career’ has been about being interested in a certain number of things and then, wherever possible, finding other great people to work with. Fortunately, there has also been a demand for articles, research or teaching courses in feminist and socially concerned aspects of architecture. So, I think I’ve been driven by finding answers to the things that bother me more than I’ve been driven by a sense that I have a career. I have also benefited hugely from being one of those first generations of white middle-class women who went in such large numbers to university through the post-war years, setting me up with the education and privileges to take such a view.

Jos Boys with Karen Burns speaking at a Parlour Summer Salon.

Creating an archive

Some people – mainly men – seem to have that career drive and sense they are going to be famous or notable from the very beginning. They start collecting letters and photos and documents for their archive when they start out, and they continue to collect them throughout their career. They will have a legacy. This became abundantly clear to me recently when an archivist friend found some letters for me in Richard Rogers’ archive – some correspondence with Brian Anson, one of the key activists in the Covent Garden revolt. This would have been when Rogers was a student or a tutor. Very early days. It made me think about Matrix and our lack of an archive.

Together with other women from the early days of Matrix, we started thinking about three years ago that we should actually try and see what we’ve got. We should explore what happens to that material, how it is stored and exhibited, how we think about it differently. Maybe we can use it as a way of thinking about what it is, especially about feminist work, that is different. What is a way of recording feminist practice that does it differently, that recognises that it isn’t straight up and down and mainstream? And also, feminist work is so often ephemeral. It’s so often women running out of energy and time, keeping stuff under the bed or in a cupboard.

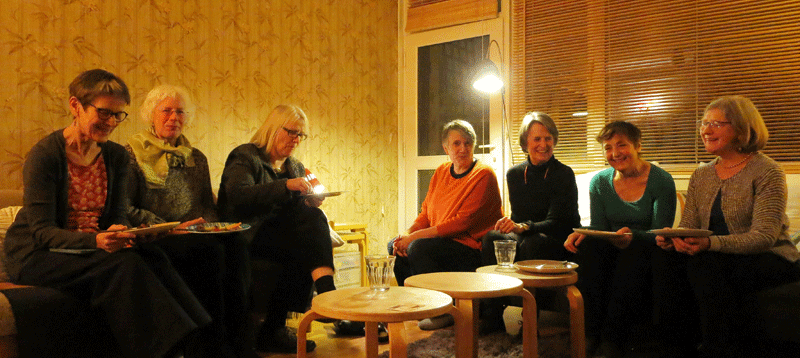

Out of this group of five, one – Sue Francis – died in 2018, a real shock to everyone. Recently we have also lost Julia Dwyer, which was really hard. So, now we are down to three, which definitely focuses the mind. We have younger people approaching us all the time who want to talk to us about Matrix before we die. We would like to work on our archive, but at the same time we’re all so busy. Since working at Matrix, Anne and Fran have run a very successful all-female practice, Anne Thorne Architects. Fran has built her own house and is building a set of sustainable houses in Norfolk. Annie is building a collective older persons’ housing scheme, intended as the last Anne Thorne Architects project before retirement. So, we’ve been meeting and talking about an archive for ages, but the doing is actually really hard. We do have a small fund – from the Bartlett UCL where I currently work – to make a start on an online archive (which will also allow us to gather materials to put in a physical archive, probably The Bishopgate Institute Archives in East London.) There’s very little online about this period of activist history in the 1970s and 80s, but we’re hoping to remedy that.

In addition, we’re trying to republish the book, which has been out of print for a very long time. Matrix has also been asked to do a small exhibition at the Barbican in London, which will open in September 2020 (with dates still dependent on how the COVID-19 pandemic develops.) This also means that previously simple tasks like visiting various past Matrix members to look at exactly what they do have under the bed, has become impossible. For now we are sharing photographs and scans, to get a sense of what is still extant. And we have great support from architectural feminists across the world, so things are finally happening.

Ex-Matrix members get together, 2016. From left to right: Julia Dwyer (1953–2020), Fran Bradshaw, Anne Thorne, Jos Boys, Lynne Walker, Marion Roberts and Susan Francis (1952–2017). Photo: Sue Ridge.

An honest account

It’s important that our archive is not just a representation of how wonderful Matrix is, or how ‘foundational it was’ but is, somehow, a complicated and multi-faceted moment in much bigger processes, both within the period when it operated, and in relation to what happened before and since. It should be as much about the difficulties as the successes. When we look at the massive amounts of drawings that were done for very small schemes, it’s not just about that scheme – it’s about how, even in a feminist circumstance, the obsessive work ethic wasn’t resisted. There was a lot of internal strife about what was acceptable as a reason to slow down. Having children was acceptable, but if you didn’t have children it could become more blurry. It’s hard in our discipline – then and now – to imagine a less intense form of working.

We need to be honest about what it was actually like working on these projects. Twenty-five to thirty women passed through Matrix and a few of them didn’t enjoy the experience. Lots of people burnt out. So, there’s something in that that needs to be recovered, but in a way that is about learning lessons from it.

It’s also about opening up more questions. How can a Matrix archive become a jumping off point for many different conversations and analyses: about alternative educational and working practices; about the role of the construction industry and of client bodies; about new kinds of design methods; about models for community participation and co-design; about what archives are for; about what constitute feminist architectural artefacts and their interpretation; about changing technologies for design and communication; about feminism and intersectionality; about social, spatial and material justice? The list could be endless. So, that’s what we are just in the process of exploring now.

Dis/ability and architecture

My introduction to work in disability was through a part-time job for the Centre for Accessible Environments (CAE) in the UK several years ago. I had been teaching in universities for quite a long time, and writing a lot about feminism and architecture. I was looking for something different.

Matrix had been quite good at working in an intersectional way, and accessibility was embedded in the projects, as well as in the work Anne and Fran have done since; but I personally hadn’t really thought about access and disability and inclusion very much over the years. I found it odd that there were no disabled people working at CAE. (Can you imagine a feminist organisation without any women in it?) This was an introduction to the charitable model of disability; where things are done for people with disabilities, not by them or even with them. (CAE has changed since then.)

The brilliant thing about my time there was that on the edges I met many extremely interesting disabled artists or people who were working in museums and galleries, who were really thoughtful and thought-provoking about how you might think about disability and ability differently. This included Zoe Partington, a partially sighted artist who had been working around access and inclusion for a very long time. I discovered that, actually, in that world of access, of disability, arts, scholarship and activism, there was a whole lot of stuff that just didn’t get anywhere near architecture, which was doing for disability what feminism had done, to some degree, for gender. It was just mind-blowing. It was so interesting.

Meanwhile, in architecture, we were still just ticking off items on the disability checklists as if disability was a completely unproblematic and functional category. And in architecture schools, disability was virtually invisible, both in the people themselves and in the curriculum.

There is a culture where architects, educators and students are not meeting or wanting to meet anyone who’s disabled, being anxious about saying the wrong thing. Of course, since then, I have met many disabled students and educators in architectural schools; who have never felt safe enough to disclose before.

Always the academic, I started reading books about disability. I began to find all this amazing stuff, and work with these amazing people across disability studies and disability arts. It was really re-energising.

An early (2008) project called Architecture Inside Out in the Turbine Hall, Tate Modern.

In 2008, I co-founded what is now called The DisOrdinary Architecture Project with Zoe Partington. This aims to bring disabled artists into built environment education and practice to creatively open up spaces for doing access and inclusion very differently; in ways that go beyond functional and legal building regulations. The platform has a core group of about 12 artists who regularly do DisOrdinary workshops and events with probably another 20 who get involved in specific projects. There is also an increasing number of disabled and non-disabled educators, students and practitioners who collaborate as part of our network.

One of the first things we did was a huge event at the Tate Modern in London when we took over the Turbine Hall to make artworks through combined teams of architects and disabled artists, in response to the brief ‘welcome all ye who enter here’. We had a planning session beforehand with 10 disabled artists working together and talking about what it is you might do around access and inclusion creatively with architects, and what it was like working with architects. The event was brilliant, with enormous enthusiasm from everyone involved. We made installations and got members of the public to join in, in myriad ways. The artists felt that it was a very productive way of communicating access issues. The architects were very enthused and said they had never thought about disability as a creative generator before. Funded by the Arts Council and supported by the access team at the Tate Modern, it was a fantastically good starting event. We have since created a whole series of different, often event-based, projects, mainly in architecture and interior design schools, but increasingly with architectural practices and client bodies. You can find more information on our website.

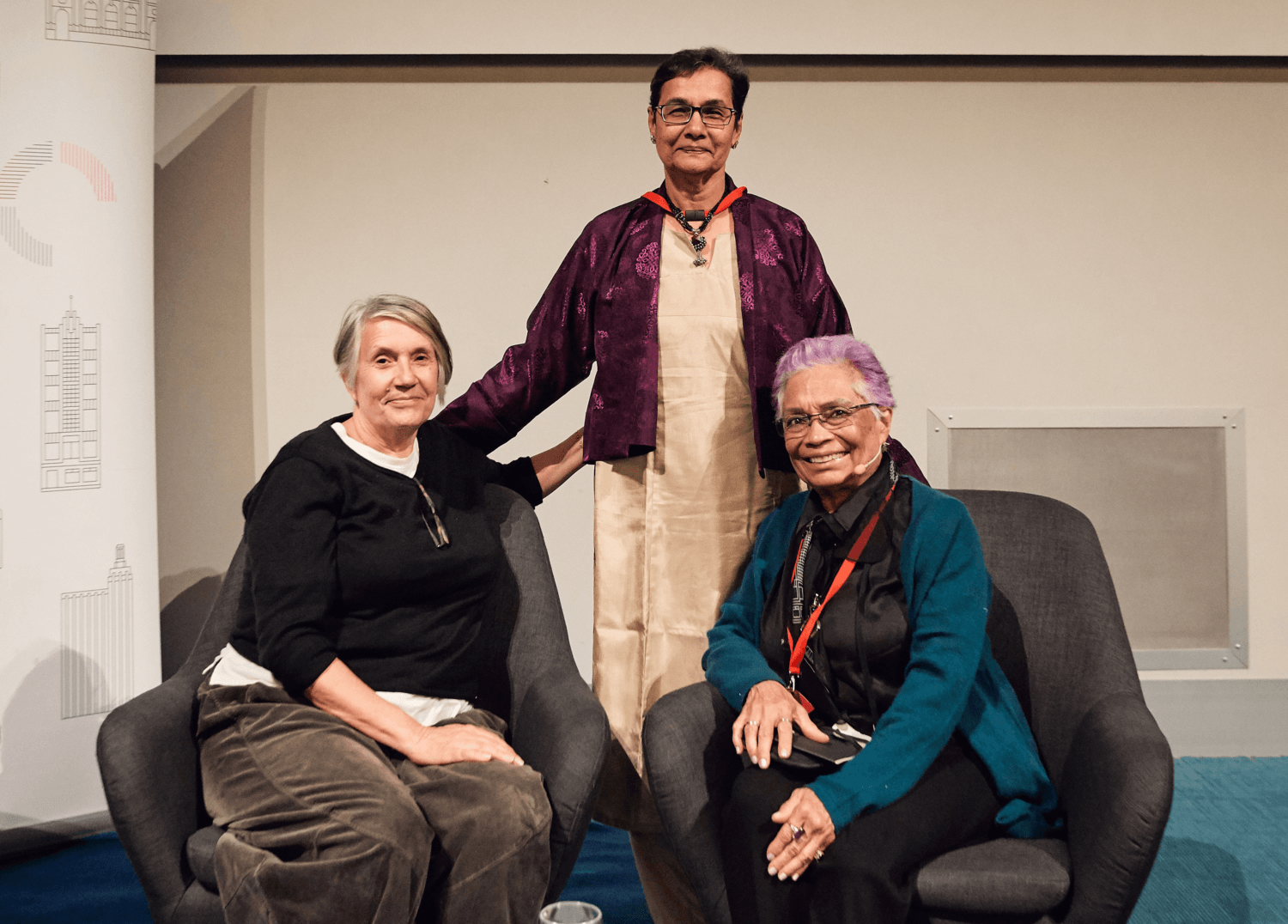

Jos presents her keynote lecture – Welcoming Unruly Bodies: Starting from difference to re-think social, spatial and material practices – at Parlour’s Transformations: Action on Equity symposium in November 2019.

Activism for life

When people talk about activists today, they consider it a rather old-fashioned thing to be. It’s acceptable to be an activist when you’re young, but you shouldn’t be an activist in your 60s. It’s kind of wrong. You should have grown out of it somehow. It’s interesting that I get that response (or that mine is somehow a rather outdated form of activism).

I manage to stay upbeat when I’m working on projects because of my inherent curiosity. I’m just really curious in a rather academic way. I’m interested in how you shift mindsets, how you change the framework of debate, how you improve the quality of debate. I’m fascinated by language and being able to find simple ways to say really complicated things. Of course, I’ve had my bad days, but the feeling doesn’t last long. And I believe in the possibility of enabling progressive cultural shifts through a snowballing of everyday small actions, repeated and repeated, until they become a new norm.

Jos Boys in action at Transformations.

A lot of activism is actually plain project management. It is just lining up the ducks in a row and getting them to move in the right way. That can be extraordinarily frustrating, because if you do it well it’s invisible, but if you don’t do it well it’s obvious to all.

I still get really angry. About discrimination and inequality. About the exploitation inherent in free market individualism and capitalism. About current frightening moves to the right that want to draw strict boundaries around categories, by marking one identity superior against the other’s inferiority (with all the violence and inhumanity by some humans to others that is already engendering). About the grievous harm being caused to the planet by the insistence on economic growth and massive profits for a few.

Being angry in these circumstances, and using your anger for good cause, seems to me to be increasingly vital. This is a challenge to the professional model of polite consensus (and to stereotypes of ‘proper’ female behaviour). One of the things that has so energised me about disability studies is its refusal of professional neutrality, both within the built environment professions and beyond.

This is the language not of access and inclusion (of letting more disabled people into buildings, of ‘empowering’ more women into senior roles) but of working towards something much more radical – social, spatial and material justice.

Jos with Madhavi Desai and Sharon Egretta Sutton, fellow international guest speakers at Parlour’s Transformations symposium.

Advice to my younger self

There are a lot of confusing moments in life when you feel like a misfit and tell yourself to just keep quiet, because you think you must be the one who’s in the wrong. This has happened to me with male tutors in particular and senior management at various times. My advice to my younger self would be to speak up and not take so much shit.

Other than that, I’m very happy with where I am, and what I’ve done in my life.

Greatest achievement

What I’m most proud of is keeping that sense of freedom – that you don’t have to just follow the line, that you don’t have to conform.

Why do you need to?

Jos Boys works at The Bartlett at University College London, UK. Originally trained in architecture, she was co-founder of Matrix feminist architecture and research collective in the 1980s and one of the authors of Making Space: Women and the Man-made Environment (Pluto 1984). Since that time, she has worked as a journalist, researcher, consultant, educator and photographer; and has published several books and research articles. Most recently she co-founded The DisOrdinary Architecture Project, bringing disabled artists into architectural education and practice to critically and creatively re-think access and inclusion.

Interview by Susie Ashworth and Justine Clark. Compiled and edited by Susie Ashworth.

Photos: Peter Bennetts, Dianna Snape, digital:works and courtesy of Jos Boys.