Canadian-born and raised, London-based, RIBA-award-winning architect Alison Brooks sat down with Justine Clark for a fascinating discussion about her early career, the value of professional recognition, urban housing project work, the challenge of balancing work and motherhood, and the future of the profession.

Starting out

I started studying architecture at the University of Waterloo in Canada in 1981 and graduated in 1988. It was a long education, because the Waterloo program involved working every other semester after the first year, so that stretches out the program by about two years. It means that you’re very skilled up and switched on by the time you graduate.

I’d had a lot of experience in different practices, including working for a very good practice before I did my thesis year, so I felt like I’d seen what Toronto had to offer in terms of its architectural spectrum. I needed to go out into the world, spread my wings. I got a two-year working holiday visa and left with my portfolio, £500 and a suitcase. I landed in London on 28 December 1988.

It was an adventure. I found a bedsit and started my job quest. I had a pretty clear idea of the kind of practice I wanted to work for. I had a list, and I went around to all the practices on my list. Back then, my ideal would have been to work at OMA, but you can’t work in the Netherlands as a Canadian. The closest thing to working at OMA was Matthias Sauerbruch who had been the project architect for the Checkpoint Charlie project in Berlin, which I really admired.

First I turned up at Peter Wilson’s office; he was packing up and moving to Germany. The 1989/90 recession was kicking in. Peter Cook opened the front door of his Georgian townhouse himself, and was very friendly. He had no work, but very graciously gave me some pamphlets and booklets, which was really encouraging. Alsop & Störmer had just laid off 70 people. It was dire. Benson and Forsyth, the great modernist housing architects of London County Council, were in such a bad way they didn’t even open the door. They shouted down the speakerphone, “We haven’t got any work, go away”!

I finally made it to the office of Matthias Sauerbruch and his partner Louisa Hutton in Notting Hill. They were literally in the middle of packing their office up into huge tea crates, also moving to Germany. Matthias Sauerbruch was very apologetic and had me in for tea, checking out my portfolio. He had heard about a competition being done by Ron Arad, and suggested I try him out. So I took up the idea and headed out to the One Off furniture showroom in Covent Garden. Ron had set up a temporary office. It was a really extreme environment – a pitch dark, cave-like, distressed-steel-clad space with only pinpoints of light illuminating crushed, welded steel furniture. There was nothing that resembled a conventional architectural office. I thought, it’s now or never.

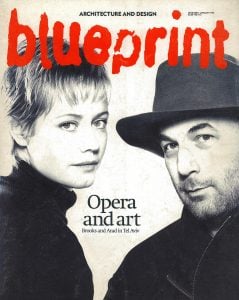

During my interview I could see the evolving competition design was also really extreme, very organic, curvilinear; complex geometry, gestural architecture. After my interview, I got a call to join the competition team – two Israeli architecture grads working under Ron, Steve McAdam and Christina Norton. We drew up the competition with rotring pens on tracing paper. Ron would appear at the end of each day covered in black metal dust from his day in the furniture workshop. It was completely ad hoc and improvised. I thought, Okay, this is something I can really learn from. After three years we formed a design partnership and I stayed for seven years. We designed and built the Tel Aviv Opera interiors, Belgo Centraal, Belgo Noord and our own studio building in Chalk Farm. It was an early example of a space covered in tensioned fabric (PVCU) roof using computer-generated form-finding. Floors, ceiling and windows were all part of an undulating, fluid language of complex curves.

London

I went to London to liberate myself from the conventions, and the comfort, of practice in North America. I happened to come across probably the most alternative version of architectural practice in London. Having said that, there were lots of super-eccentric freestyle designers and makers working in London at the time.

I found it really liberating. London’s culture really nurtures eccentrics. The more alternative you are the better. Also, it’s such an extreme place. It really is hard to live in London – it’s very dense, it’s very old, it’s expensive, there’s a lot of creative friction between all these different populations. It’s abnormal to be normal.

London is considered part of the ‘old world’, constrained and limiting. We all assume that the ‘new world’ is much freer. But actually, I think the new world can be far more conservative than the old world. The cultural outlook of London is more new than, say, Toronto. We can see this in contemporary politics.

Partners in design Ron Arad and Alison Brooks.

Setting up practice

I had a really fruitful creative design partnership with Ron Arad. Then, at a certain point, I experienced the seven-year itch. I felt I needed to find a context in which I could work in the public realm. I wanted to design large-scale projects that had a civic impact. I was always interested in working on the social project of architecture, which is urban housing.

In June 1996, when my son was nine months old, I set up my own practice [Alison Brooks Architects/ABA] and started doing competitions. It was just at the point of transition between hand drawing and computers, so I drew my first competition by hand, in the spare room of my house, on A1 sheets of paper. I had about a month’s paid work of finishing a planning submission. I helped another practice with a competition.

I designed a business card and letterhead on a Mac Classic, and wrote two letters to prospective clients along with a printed A4 portfolio. I told them I’d set up in practice and I was available. That was my business plan. One letter was to a couple based in London and the other was to a German developer/contractor.

To my amazement, about a month later I got a call from the German developer, asking if I would consider designing a hotel interior in Germany. It was quite big, a 70-room spa hotel on the island of Helgoland – more or less in the middle of the North Sea. They had already employed an architect and wanted me to develop a hotel concept and the interiors. It was an incredible break – that project kickstarted my practice.

I set up an office of five – German, Austrian, Swiss, ‘Kiwi’ and one Brit. A mini-EU. We bought some secondhand PowerMacs and a fax machine, and started working from the living room. We worked on that project solidly, frantically, for three years. I was flying to Hamburg all the time and we finished it in March 1999. This coincided with the birth of my second child. The Atoll Hotel was very successful in design terms – it won lots of awards and was published in the AR – but it didn’t help me win more work in the UK. All my contacts were in Germany and Helgoland was just too remote for client visits.

So, in a way, I had to start over again in 1999. Leading up to the opening of the Atoll hotel I did non-stop competitions to try to win more work. Europan ’99 – housing in Harlemermeer, Netherlands; Concept House ’99 – I came second with ‘FUL House’; Young Architect of the Year, coming in third (I was 9.1 months pregnant in the competition interview); the Urban Splash/Britannia Basin competition for housing in Manchester. My team and I went for broke doing all these competitions (literally). I think being pregnant gave me more energy.

After my second son was born it was really tough for ABA; we had no work and had just about run out of cash. I paid staff using my credit card. My office, by now in an Islington warehouse, had shrunk to two architects.

Amazingly, the other client I’d written a letter to in June ’97 called me up. She asked if I would design some built-in bookshelves – part of a house renovation after a major fire. I remember taking my three-week-old baby to visit the site. I had no other choice.

That shelf commission turned into an enormous project. This client didn’t just need shelves. She needed an architect to design and manage an entire residential conversion including an extension to the front. That was phase one – the V House. While it was under construction she asked if I would design a guesthouse in the garden. They were pretty happy with that and said, “Oh, can you also design a carport? And the landscaping? And furniture?”. So, it became a complete work – the V-House, X-Pavilion and O-Port.

The VXO House was an essay on architecture working as landscape architecture and art an integral part of the architecture. It was about amplifying the modernist language of the original house by expressing each element as an autonomous, sculptural ‘object’. These objects included a suspended staircase, structure in the form of giant letters and a site-specific wall drawing by the artist Simon Patterson. We brought light into the centre of the house by making an atrium-like double height dining space, split levels, bay windows. The VXO House was published all over the world and, most importantly, won a RIBA award. It was a proper stepping stone into building my practice; finally I had a portfolio piece that was accessible and visible in London.

It’s amazing how developers, even to this day, will say to me, ‘Oh, I love that house. Can you do something like that?’. Even though they’re asking me to design say, a 200-dwelling development on a really tight urban site. The essence of that project – its spatial flow, control of detail and sense of humour – is somehow really clear and accessible. It gave confidence to future clients that I can build well.

VXO House in London.

Work and motherhood

While I was designing and building the VXO House, my office had shrunk to two, and then one employee. It was just me, my VXO project architect, and the baby until 1pm, then I’d race off across town to pick up my older child, who was three. I did that for six months until I hired a new nanny. That was probably the toughest time of my career, having a new-born and a three-year old, and not really having enough income for childcare for about six months, and trying to keep the office going. I remember spending a lot of time next to the fax machine – email didn’t exist.

The six months of half days did allow me to discover a new world. With my first child, I took three months maternity leave and went back to work full-time. So I’d missed out on all that socialising/mothering activity that happens when you’re at home with your baby. With my second child, I had three weeks off, and six months working half days taking my baby with me. I got an insight into a kind of community support system, of picking your child up from nursery at 1pm, meeting other mothers and spending afternoons together sharing experiences. I’d never known about that social structure with my first child. That was very helpful. It gave me, my partner and my kids new (non-architect!) friends and a safety net, which meant I wasn’t totally dependent on my nanny or my husband. These kinds of networks are critical for a professional working woman.

I think there’s still huge pressure on working women when they have children. We still feel that we have to take the majority of the burden of childcare, pick up the pieces, arrange social events, birthday parties, food shopping, clothes, the home, all that stuff. We’re expected to do it all. The burden of home work is not easy to share equally – physically and psychologically. And we also have a guilt complex if we don’t do it all perfectly.

My mother used to say that the idealised image of women as an ‘at-home domestic goddess’ after kids is a myth. Historically, working-class women in Asia or Europe, or pioneer women settlers in North America, all had to get back to work ASAP. She’d joke, “They just slung them onto their backs and kept going!” This is a bit of an exaggeration, but she was making the point that the idea of women destined to retire from working life to raise children is a fallacy. It’s a product of the post-war era of middle class wealth, modern conveniences and the positioning of men as sole providers to the household.

In my view that was a kind of culturally pervasive myth that allocates power and authority and control disproportionately to men; where women became subservient to other family members. But it’s also indicative of a consumer lifestyle. It’s a particular socioeconomic formula that led to women suffering from dependency and conformism, and in the suburbs of North America, social segregation and isolation. All these things have still held women back since the 1950s. Richard Hamilton’s art from the 1960s depicts this phenomenon perfectly. You could argue that women were suppressed so much more in the 19th century – they didn’t have the vote until 1920, they weren’t allowed into some universities until the 1970s. But there are many, many things that have contributed to the suppression of women’s abilities. Even the principle of suburbanisation – mass mobility, the oil industry, the development of rural land into suburbs, zoning. The division of labour and social roles are embedded in the structure of contemporary life. It’s a cultural system that’s very hard to shake off.

Newhall Be in Harlow, outside London.

Housing design

Housing design is city-building and civic infrastructure. So I see it as the most important task of an architect. It’s notoriously difficult to try to change the fundamental components, or ambitions, of a housing project when your client is a developer. In the UK, dwelling sizes are determined by the London Housing Design Guide; these are simultaneously a minimum and a maximum in terms of space standards. There’s a huge reluctance on the part of developers to incorporate other kinds of space into a residential development, such as a crèche or commercial space. Other uses place a long-term management burden on the developer.

It’s also difficult to challenge the way domestic space is described. A good example of this is the lack of home offices. No developer brief includes a home office space in an apartment. Generally, the economic model that drives housing is based on bank mortgage surveyors – possibly the most conservative people in the world. They have a lending formula based on standard, historic models – the two-bedroom flat and the three-bedroom flat and the one-bedroom flat – and it’s very difficult to challenge a bedroom-based valuation formula. But working from home is a universal phenomenon now; every home is a potential start-up. There’s enormous value in that, unacknowledged.

I incorporated work spaces in Newhall Be, my project in Harlow outside London. It was a design competition and the landowner was looking for new ideas. I invited the developer to join me in the bid and designed typologies that I felt were ideal. They had two bedrooms plus a home office on the ground floor, an adaptable roof space and high ceilings. The home offices were positioned at the front of the house. They were legitimate home work spaces that were also part of the streetscape, so public and visible. I have been able to include similar home work spaces in a few developments – in Bath and Cambridge – but not all of them.

In recent projects where the client hasn’t permitted mixed uses, we have introduced the simple concept of expanding foyer spaces so that they become co-work spaces. We have fought for these, and have won. We are embedding co-work spaces in the overblown, too big, ridiculous lobbies that you get in residential developments. We add a couple of big, long tables, a few plugs and a mini kitchen and coffee machine, and people will work there. Suddenly it becomes a space of potential exchange, and another way of creating opportunity for people to meet, for community and communication.

People work everywhere now. It’s important to provide that choice – you can work from home, or you can work in the foyer, or you can work in the café or library down the street. Making those big foyer spaces multipurpose and embedding that kind of spatial potential in a residential development is actually quite easy, and is non-threatening to clients in terms of management.

It’s important to convince residential developers that they’re building more than just a piece of real estate exchange. Every flat, every apartment is a start-up, potentially, and a civic building of the future. If you think of every residential development as a building with start-up space for 100 new companies, you can suddenly think differently about the set of demands on the space. Maybe the entrance hall should be part of the living room so that you can segregate the private realm of the flat from the public, so you can have people coming in for meetings.

This changes how we think about the space of the home, and how we can adapt it to suit contemporary lifestyles and needs and households.

Albert Crescent, a mixed use scheme on the banks of the River Avon in Bath.

Buildings and the public realm

When approaching a project, I always think about other ways the building could be used, and alternative futures for the building – as well as fulfilling the client brief, of course. Embedding things like generosity and longevity and adaptability into a project is really crucial. It’s something I’m constantly pushing for because that’s part of sustainability in its widest sense – social sustainability, adaptability, long-term performance and environmental performance, but also cultural value and collective memory. If you can produce a building that serves a very wide constituency over a long time, your architecture becomes part of a cultural fabric that, in theory, can really enhance people’s lives.

I apply that same approach to housing. It’s not just about libraries and theatres and art galleries. It’s crucial to embed generosity and adaptability and to future-proof housing as a typology. The goal is to design a really good urban building that happens to have people living in it – but it could have many other uses.

How do you provide a framework that will allow alternative lifestyles and different uses in a building? This question was the catalyst for the idea of generosity of space, of proportions, ceiling heights. Generally, the higher the ceiling, the more adaptable the space is. And those proportions and that generosity is also legible on the exterior. You can read how high the ceilings are on the facade of a building. Facades convey messages. Whether it’s housing or a public building, they are part of the public realm, part of how you understand that spatial framework. They contribute to the life that’s possible in the space of the street or squares or parks.

All architecture is a frame or a backdrop or context for public and civic life. There is a reciprocal relationship between all kinds of building – between architecture as both a formal entity and a spatial entity, and the way it forms a context for other things to happen, for collective lives. The physical nature of the built environment, of our shared space, is really important. We form attachments to places that are well built, beautiful, meaningful, that embed history and memory and time, and these things are fundamental to human nature. I don’t think that need will disappear.

The Exeter College Cohen Quad in Oxford.

The value of professional recognition

When I won my first RIBA award with the VXO House, the impact was huge. I received all this free publicity and, as a young practitioner with no clientele, this was enormously beneficial. The RIBA award system is tough. It’s peer review, and your work is scrutinised by many, many architects. It’s a serious matter, but so many benefits come with this kind of professional recognition.

Sometimes projects take so long to realise that after a few years you don’t really know if it’s good anymore. You thought it was good when you won the competition, but projects take years to build, especially when they’re in phases. You have models lying around the office, and you look at them and they start getting bashed up, and you think, “Hmmm, is that really a good project?”

So, when a project is complete and your peers review and award it, it’s really important. It’s a symbol of confidence in your work. Many architects suffer from insecurity and a lack of confidence, and this affirmation is very helpful – especially when it comes from peers, and from actual site visits. It’s not just looking at photographs. It’s informed by interviews with residents or occupants, and considering how the building contributes to the streetscape. It’s judging what is the most successful piece of architecture. It’s a multifaceted acknowledgement.

Women in Architecture awards

When I attended the Women in Architecture Awards for the first time in 2012, I’d never been to an architectural event that wasn’t 95% men and 5% women. There is a certain tension when you’re in a room with 850 men and 50 women. There’s always a slight sense that it’s a boys’ club, you’re in a very obvious minority, and you’re an observer. So, to be at a large-scale event with so many professional women working around architecture was amazing.

It was a very warm, unthreatening atmosphere. I felt genuine pleasure in meeting other women who I’d heard of but never seen in the flesh. There were so many women in practice who I’d never encountered in my 20 years of practice, which is mind-boggling.

The speeches women architects give at the Women in Architecture Awards are proper lectures. They’re well-prepared, informative, enlightening talks. One year, for example, Shelley McNamara and Yvonne Farrell of Grafton Architects gave the keynote speech; it was a manifesto, an ode to architecture. Their talk was beautiful – inspiring and heartfelt and meaningful.

It was the same with Odile Decq. When she told her life story, it was amazing. Until then, I didn’t know that she founded her practice, and that Benoît Cornette joined her later. She’d been running her practice for six or seven years when he joined, but everybody assumes (me included) that he was the master, and Odile was his partner who joined him. We’re so conditioned into thinking that the leader is always the man. Her story was amazing.

These life stories have the kind of honesty that you just don’t get in a room full of 600 men, who are all trying to outwit each other – the banter, the jokes, the competitiveness. Usually, there’s an unwillingness to reveal what’s really going on. The Women in Architecture Awards have a refreshing honesty – and you learn something at each event. It’s not something to be suffered through like some other awards ceremonies. It really enhances your feeling of participation in a collective project, which is improving the built environment for society at large.

Involvement in public life

I have been rewarded by my profession, and I feel that I owe it a duty of service, that I have to give something back. I feel a responsibility to make my voice heard. It’s also very important that women have visibility in the profession, because there are many women who are doing really important work who are under-recognised. They may be partners in practices, but you’ve never heard their name. We’ve lacked many diverse voices in the profession. So, I feel it’s my duty to the profession, and to women professionals, to be involved.

The big challenges

Architecture is a shared project. There is a fellowship that architects from anywhere in the world feel when we meet each other and get together and speak. You have a shared understanding. There’s a lot of work to be done, and we’re doing our best. There’s no time to waste bullshitting about how great you are, or how you’ve got all the answers, and everybody else is wrong. That era is over… But there are still vestiges of it in the architectural world, and the property world, and the real estate development world.

It’s a shame that we aren’t able to tap into the fellowship more, to help reinforce our place in society and our value as professionals who are trying to serve the public and trying to serve society at large. It’s a shame the building industry doesn’t value us, and is so adversarial, litigation-ridden and contract-led. There’s a lot to be done in legal terms, in changing the way in which architecture is prepared and delivered.

In the current process, everybody suffers. There are the unreasonable fees and the hyper-competitive nature of contemporary practice, and the way our institutions don’t always support what we do. There’s the liberalisation of our services, so there are no norms in relation to fees and services, or limits on what we’re expected to deliver. I often refer to the HOAI, the German system, which has a complexity matrix and a responsibility matrix. You just identify the fee percentage that’s appropriate on that scale, and you fine-tune it with the client. It ensures that architects are properly paid for their work, and it’s not just who undercuts who the most.

The problems are obviously beyond gender – but they’re not unconnected. Fee undercutting’s absolutely rife. If architects became better businesspeople, and there was a better structure for fees, you could pay people better; you could resource teams better with more people, so there wasn’t so much pressure on everybody to do so much overtime. There would be many big impacts if there was a change to the fee structure. All the gender issues wouldn’t disappear, but quite a lot of them would recede a little.

‘The Smile’, a public pavilion at the 2016 London Design Festival.

Solutions

The profession needs to fund proper, evidence-based research (metrics) that prove the value of what we do, the value of good design and innovation and all of the things that we talk about as being important and improving people’s quality of life, their behaviour, performance and their sense of self-worth, their wellbeing, all these qualitative things. We have no evidence. We have no resources.

There are buildings out there that are very badly detailed, and there are buildings that are beautifully detailed. Do architects share those great details in a scientific way? In a way that describes their dimensions, their properties, the way they were built, so that other architects can learn and use that technique in their own buildings? No! We are constantly reinventing the wheel.

Every young architect thinks, “Okay, I’ve got to sit down and figure out how to detail a rain screen wall” and they literally start from scratch. We really hamper our own ability to be taken seriously by the world at large, or by our clients, because we have no accepted professional standard of techniques and processes and examples, where we prove performance criteria, value and outcomes. They do this in science and medicine, and it supports the work of professionals in those fields. But it’s not part of our contextual culture, and it’s really starting to take its toll. I’ve thought about this as a business or project – a kind of open source, online platform that can be a repository for proven, high performance details for buildings that can be used as a resource for everybody in the profession.

Buildings are complex. Nowadays they’re getting more and more complex in terms of systems, electrical, mechanical and environmental systems – but we should be masters of all of that, of our tools and our techniques. We are starting to deskill in terms of expertise in delivering the full project because of the switch to design and build, where architects aren’t appointed all the way through the project. We need to change that.

Advice to your younger self

More self-confidence would have helped me a lot. I would have liked to have done more with getting out and meeting people, directly approaching potential clients, which is super scary when you’re starting up your practice. As a sole practitioner, it’s something that you will put off for years literally, rather than face that awkwardness. But, actually, it’s not that awkward, and there’s nothing to fear about approaching somebody, inviting them for lunch, and having a conversation.

I should have got some kind of bank finance so that I could properly equip my office sooner than I did. I always thought, “I can’t get a loan, I can’t be in debt”, but when you look at other business models, every single start-up and small business gets finance to get their enterprise going. They don’t even think twice about it. The first thing every MBA grad in the universe does when they set up a new business is to get some kind of business loan that gives them a footing to properly equip their business. I should’ve done that, rather than living hand-to-mouth for so many years, relying on the fees coming in.

I would also advise my younger self not to compare myself to other people, to be myself. As a creative discipline, your authorship, your voice and your approach to things is unique, and it has value in its uniqueness. Nobody can take that away from you. You just have to believe in that and not fall into the trap of comparing yourself to people who’ve come before, or men who have come before, or peers who are around you. It’s absolutely pointless to compare yourself, because you will always offer some kind of difference that has value.

I think a lot of young women in particular suffer from a lack of self-confidence, and that is a societal thing. I was, or even still am, a product of that kind of conditioning, where I always thought, “Oh, God. I’m never going to be the authority on anything, there will always be a man who knows more than me, or has more authority or more right to actually be the leader”. It took a long time for me to realise that, actually, I was the one in the room who knew more about a certain topic than anybody else, and I should let them know, and not just let the men hold the floor and pontificate.

So, self-belief is important. You may think that you can’t do it, but actually you can. It’s a state of mind. It took me quite a long time to get to this point, though. It was not there in the early days. But I always had a belief in my ability – a fire in me to try to design in a way where I was pushing something new, that I was going to try to break new ground and do something that didn’t remind me of anything I’d seen or done before. You could call that ambition. I think historically young women have been conditioned to hide their ambition.

I always had an instinct, a need to invent, but that invention needs to be grounded to things that I know from personal experience. I often give talks about the ancient forms and formats of architecture – archetypes – that everybody understands and recognises. These can be transformed and translated into something new.

I always feel like there is a discovery to be made in the next project. I’ve got to make that discovery, I can’t repeat myself. It’s an exciting way to approach projects. It’s always spurred me on to conquer the next challenge, discover that new territory.

Alison Brooks is a London-based architect, advocate and educator. She is the only British architect to have won all three of the UK’s most prestigious awards for architecture: the RIBA Stirling Prize, Manser Medal and Stephen Lawrence Prize. Alison has become a public voice for the profession, advocating for the role of housing as civic building, the resurgence of building craft and the use of timber in architecture, and also lectures internationally. In 2016 she received an Honorary Doctorate of Engineering from University of Waterloo, Canada. In 2018 Alison was appointed as the John T. Dunlop Design Critic in Architecture at Harvard GSD and taught a Masters in Collective Housing at ETSAM, Universidad Politécnica of Madrid.

Founded in 1996, Alison Brooks Architects delivers projects ranging from urban regeneration, master planning, public buildings for the arts, higher education and housing. ABA’s award-winning architecture is born from intensive research into the cultural, social and environmental contexts of each project. The practice seeks to develop authentic, responsive solutions for our buildings and urban schemes, each with a distinct identity.

Photos: Paul Riddle, Dennis Gilbert

Interview by Justine Clark. Compiled and edited by Susie Ashworth.

1 comments

Pippa Hurst says:

Dec 2, 2019

There is so much insight in this – much of what Alison says applies not just to women in architecture but to women in general. Thanks for sharing the wisdom Alison and Justine. Bookmarking and sharing!