Design historian Catriona Quinn reviews Deborah Sugg Ryan’s recent book, which brings previously invisible examples of suburban modernism into the spotlight.

Ideal Homes, 1918–39: Domestic design and suburban modernism

Be on your mettle for a vocabulary in this book that is seldom associated with modernism: ‘Tudoresque’, ‘Jacobethan’, ‘Tudorbethan’, ‘Jerrybethan’, ‘By-pass variegated’ and ‘bungaloid growth’ were amongst the wittily derisory terms for the hybrid architectural styles that took hold in British (and Australian) suburbs in the 1920s and 30s. But how many publications take the study of suburban domestic design seriously, let alone mount a convincing argument for the inclusion of such homes as examples of ‘Suburban modernism’, in a field of history that generally renders them invisible? In Ideal Homes 1918–39. Domestic design and suburban modernism (MUP 2018), an entire chapter, ‘Nostalgia: the Tudorbethan semi and the detritus of Empire’, is devoted to these ‘half-baked pageants’ of architecture, making the case for their status as pragmatic, if romantic, solutions to consumers’ desire for a modern comfortable home.

Author Deborah Sugg Ryan is a leading UK academic whose theories on the topic of suburban modernism also reach popular audiences through the BBC2 series A House Through Time and her popular Instagram feed @vintageprofessor (#thisiswhataprofessorlookslike). Her new book covers the type of content and arguments rarely seen in Australian publications on modern design history: the invisibility of certain styles, their potential for inclusion and a commensurate re-evaluation of significance – my own area of academic interest.

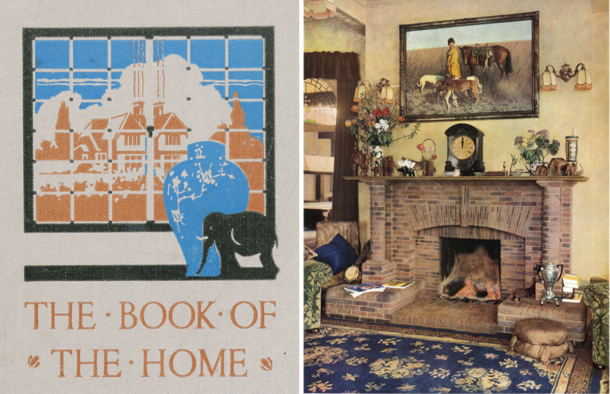

The Book of the Home cover from the 1920s depicts ebony elephants and chinoiserie urn (left). Similar manuals for the decoration of bungalow houses were widely available in Australia. By 1937 the teak elephants had migrated to the mantlepiece in a publicity image for Claygate Fireplaces (right). Sugg Ryan points out that despite the popularity of these so-called ‘detritus of empire’ in the interwar period, little serious attention has been paid by design historians to the meaning of the taste for the exotic in the suburban home. She argues for their significance as ‘potent icons’ of imperial nostalgia and family identity.

Sugg Ryan’s book is essentially concerned with home ownership in 20th century Britain, in particular the English suburban semi of the interwar period. Through an interdisciplinary approach, this book aims to depart from previous social and design histories in redressing gendered roles in decoration and in presenting a complex view of taste, decoration and class identity. Drawing on informal family photographs as an important source, Sugg Ryan’s interest is in the lived-in house decorated by the home owner, who subscribed neither to one single style alone, nor to the tenets of modernism, resulting in interiors that show evidence of modernist style filtered by the impact of the owners’ preferences and financial circumstances. Key chapters cover interwar housing and the ideal home; class, gender and home ownership in suburban Britain; the tropes of modernism that polarised ‘good design’ and ‘bad design’; the importance of the new labour-saving devices and the idea of the professional housewife. The chapter on the hidden modernity of the nostalgic Tudorbethan semi is well balanced in a broader history of the design and decoration of the interwar suburban home.

Sugg Ryan’s focus is on the meanings of these modest suburban dwellings as they evolved over time, to home owners with aspirations to modern living. She examines the idea of ‘home’ and what it was to be ‘suburban’ and ‘modern’ in the context of interwar suburbia. Rather than the Bauhaus dictums of the modernist movement, Sugg Ryan opens up an idea of modernism as a ‘tension between the longings for the past and the aspirations for the future’ expressed through a ‘mixture of symbols of progress’ such as labour-saving efficiency and new English hybrid forms that modernised traditional forms. Like Penny Sparke’s table-turning scholarship on the modernity of Elsie de Wolfe, Sugg Ryan’s view of the modern interior has moved beyond the simple aesthetics of minimalism and argues instead for an understanding of the reuse of the styles of the ‘detritus of Empire’, found in Tudorbethan forms, as intrinsic to the suburban vision of the Modern. She contests cultural critics’ derision of popular revival styles, characteristic of the wider denigration of suburban life by the architecture and design fields of the 1960s. ‘Stockbroker Tudor’, ‘mantelpieces’ with their teak elephants, a ‘Henry VII dining-lounge’ and the ‘freakish originality’ of a cactus wallpaper scheme (all illustrated in the book) are cited as examples of interiors labelled ‘bad design’ – correlating with striking similarity to the types of furnishings mocked by Australian architectural critics of suburban taste.

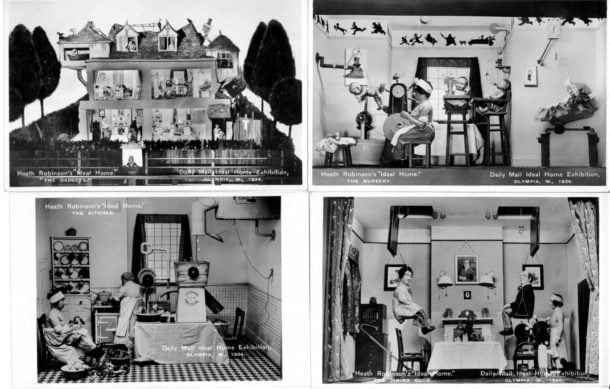

Postcards of ‘The Gadgets’ by Heath Robinson at The Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition, 1934. Concepts of efficiency and liberating labour-saving devices, which became symbols of suburban modernity inside the home – regardless of the aesthetics of its exterior – had, by 1934, become so prevalent as to be lampooned in this satirical installation seen by the crowds at the Olympia exhibition.

Reflecting the book’s origins in Sugg Ryan’s earlier doctoral thesis on the London Daily Mail’s Ideal Home exhibitions of the 1920s and 30s, the references are extensive (25 pages of chapter notes, an 18-page bibliography) and include much original archival research. Sugg Ryan, a former curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum, draws on its Archive of Art and Design, the Geffrye Museum, London Metropolitan Archives, MODA, Middlesex and less well-known collections such as The Mass Observation Archive, containing social research on everyday life in Britain, as well as an extensive list of household guides and commentaries published in the 1920s and 30s. The book is illustrated with 60 black and white images and 20 colour plates, mostly drawn from contemporary ephemera, some of which were in use in Australia and are held in our most important collection of domestic trade catalogues, at the Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection. Inspirationally, the author lists a stash of ‘middlebrow’ domestic novels, TV programs and films (I immediately ordered The Diary of Nobody and Betjeman’s BBC Metroland documentary) among her original sources – often underestimated as references for legitimate study of interiors. Sugg Ryan’s understanding of the key literature of her field is comprehensive and her list of secondary sources provides a guide for any serious student of the topic.

To accumulate a comparable bibliography on Australian interiors would be a challenging task indeed. It would be difficult to imagine a serious discussion of a Tudorbethan semi as a typology of suburban modernity in Australia: the bias embedded in our historiography shapes the inclusions and exclusions of our field.

Certainly, some Australian exhibitions and catalogues – such as Homes in the Sky (Caroline Butler-Bowdon and Charles Pickett, 2007), Modern Times (edited by Ann Stephen, Philip Goad and Andrew McNamara, 2008), Sydney Moderns (edited by Deborah Edwards and Denise Mimmocchi, 2013) and Brave New World (edited by Isobel Crombie and Elena Taylor, 2017) – have engaged with the interwar interior, but these, largely written by art historians, have lent disproportionate emphasis to single events like the 1929 Burdekin House exhibition or the solitary figures of Fred Ward and Cynthia Reed, to the exclusion of the multiple other modernities in practice. Sugg Ryan’s critique of the narrowness of the British field of literature is mirrored in Australia, with Nanette Carter’s Savage Luxury (2007) and Rebecca Hawcroft’s The Other Moderns (2017) providing scant exception to the dominant histories of interior decoration. In my view, the reader would need to return to James Broadbent’s ‘hard won, hard done by’ three-piece Genoa velvet lounge suite in his essay ‘What is Feltex?’ in the 1989 catalogue Demolished Houses of NSW, to find anything approximating Sugg Ryan’s re-evaluation of suburban taste, in the Australian context.

Sugg Ryan’s personal story of the gestation of this book – associated with spending long periods of time at home with her children and, more recently, recovering from serious illness – was compelling in underscoring how fundamental her own family, including her parents’ and grandparents’ history of suburban home ownership, was as a catalyst to her work. Keeping ordinary people’s histories, rather than heroic architects’ and designers’, at the heart of her work distinguishes this book from others. The findings are shaped by primary sources, rather than locating examples to fit “predetermined theories of Modernism and modernity”, allowing the importance of home ownership, decoration and social standing to determine the outcomes.

Sitting room of 17 Rosamund Road, Wolvercote, Oxfordshire, 1995. (James R. Ryan) Sugg Ryan’s personal experience of home ownership, beginning with this time capsule house, was a catalyst to the thinking underpinning the book’s research. The living room retained its compact leatherette three-piece suite that combined ‘modernistic’ curves with ‘Jacobethan’ studs.

This book succeeds in contesting the exclusion zones design history has placed on what Kjetil Fallan, an academic leader in the discipline, calls “the vast masses of modern material culture not conforming to the modernist ethos”, with Sugg Ryan calling the field to account in its pursuit of the endorsement of the Modernist Movement alone, with the exceptions escaping these narrow parameters few and recent. When the author refers to multiple modernisms that are inclusive of interwar ‘medieval modernism’, ‘liveable modernism’ and ‘amusing styles’, you can be sure this book is going to open the reader to entirely new and unconstrained ways of thinking about suburban interior decoration.

Catriona Quinn is a design historian with the University of NSW Faculty of Built Environment with expert knowledge in the history of 20th century interiors in Australia, particularly inter-war and post-war design, decoration and furnishings. Catriona spent fifteen years as a curator with Sydney Living Museums, developing a wide scope of interests in the way Australians decorated their houses. As a PhD candidate, her current focus is on the role of the client in the designed interior and a more complex understanding of expressions of modernism in Australia.