How might we subvert, challenge or rethink elements of architecture culture that disadvantage women and diversity? Tania Davidge argues for the value of engaging in the public culture of architecture, among other things.

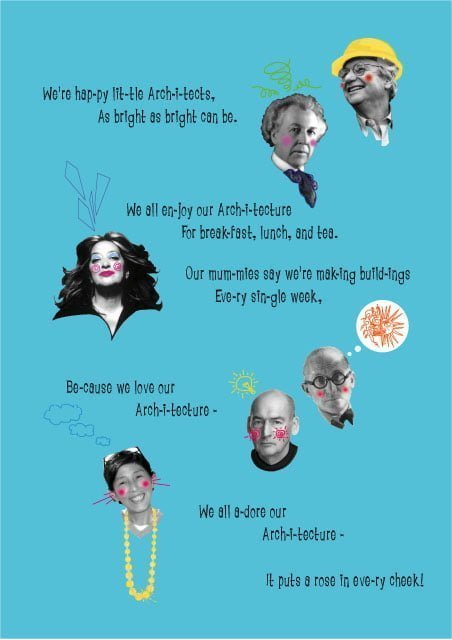

- Advertisement for Architecture, Tania Davidge.

As I write this on a Sunday afternoon I’m listening to my husband recite The Gruffalo to two small children who were, up until two minutes ago, climbing all over me. I’ve already had two cracks at writing this and, to be perfectly honest, I had not expected it to consume so much time or to be so difficult. I’m not complaining about this. Rather I’m pointing out that these difficulties have arisen because the issues I have been asked to reflect on are deeply important to me and have influenced my architectural practice in profound and liberating ways.

Justine Clark and Karen Burns, in their respective articles, have succinctly and devastatingly articulated many issues with which I have had a firsthand relationship. Reading the statistics I feel that it’s rather ironic that I am still plying my trade in the architectural profession at all. Perhaps I am a glutton for punishment, but I would like to think that I am an optimist (perhaps with architecturally masochistic tendencies).

Back to the children… Having children deeply affected my career path in ‘traditional’ architectural practice. There is nothing like suddenly becoming time-poor, exhausted and completely responsible for another life to put things in perspective. Things I complained about yet put up with as part of everyday life in an architectural practice, I no longer had time for. It wasn’t that I was complacent before I had children – it’s just that many issues became irrelevant after having them. I became more interested in putting my energy into fighting the battles that I had a chance of winning or at the very least influencing.

Advertisement for Architecture, Tania Davidge.

Having children was the catalyst for initiating OpenHAUS Architecture in partnership with Christine Phillips. Christine and I do not have a traditional architectural practice. We often explain this by saying that we do not currently make buildings. Instead Christine and I are primarily interested in developing strategies that engage people with architectural discourse and architectural practice. We believe architecture has the ability to affect people’s lives every day and a better-informed public leads to better spatial and urban outcomes. Engagement is our main agenda.

This leads me to reflect on Karen and Justine’s writings from a professional perspective. For me, the under-representation and under-compensation of women in the architectural profession is part of this broader issue of engagement. How the profession and the discipline engages with women, and the kinds of opportunities women are exposed to that facilitate increased levels of participation, needs to be carefully considered in light of this disparity. Alternative ways of engaging women need to be developed and promoted.

Rather than dwelling on issues of discrimination and bias I am interested in identifying strategies that subvert, challenge or rethink elements of architecture culture that disadvantage women and diversity. Gender inequity and diversity needs to be engaged with on multiple levels: at the level of architectural discourse; at a professional level; and at a personal level. At every level we need to ask ourselves – what strategies might we employ to remove the barriers to practice for women and to increase participation in architectural culture?

In 2011, Jeremy Till made his 30% pledge stating he would only accept invitations to “events/series/books that have at least 30% female representation”. Till’s pledge addresses the issue of female participation at the level of architectural discourse. In Australia, women are under-represented as speakers, in the architectural media and as members of the Institute. We need to think beyond traditional networking and develop strategies that help women become more visible at this level and to the profession as a whole. The importance of women role models cannot be understated.

Till’s pledge also evokes a possible strategy in terms of workplace culture. Unconscious bias has been identified as one of the primary barriers to gender equality and diversity. Without clear and explicit decision-making criteria we rely on cognitive shortcuts when assessing information and fall back on stereotyping to fill in the gaps of our knowledge.1 Unconscious bias has the most influence when decision making involves ambiguity, time constraints and when processes lack transparency, scrutiny and qualified objectives.2 For example, when faced with a clear ‘fit’ in terms of hiring the decision-making process is straightforward – the outstanding candidate will typically get the job. However, in cases where the choice between candidates is not clear, the gaps in a candidate’s potential are filled out by a reliance on subconscious stereotyping. In these cases it is significantly more likely that the candidate chosen will fit the stereotype and reinforce dominant stereotypes and normative workplace practices.

Actively combating unconscious bias requires a commitment by an architectural practice to implement strategies that deliberately address bias, putting in place transparent criteria for promoting, hiring and compensating their staff. Perhaps the first step in creating a more diverse and equitable workplace culture would be to create a pledge list of Australian architecture firms committed to proactively addressing unconscious bias and inequality in the workplace.

When faced with the intensity of architectural practice and the realities of an entrenched professional culture it is easy to feel ineffectual. It can be difficult to discern what we can do individually to improve opportunities for participation and diversity. How can we engage with this issue in such a way that we feel like we are making a difference?

Firstly, we need to think about what our responsibilities are. I believe we have a responsibility to be aware of the statistics that relate to the under-representation and unequal compensation of women in the profession. An awareness of inequity influences our everyday practice and can act as a catalyst for change. For me the statistic that only one out of five women architecture graduates register as architects was so astounding that registration became an important professional and personal goal. This is not to imply that registration is the answer to the problem. We pick our battles and effect change in small increments. Sometimes these battles are large – we might start our own practices so that we can create a different kind of professional culture that provides us with the balance and flexibility we need (I am pleased to say I know of both men and women who have taken this route. )

More often than not it is the small things that accumulate to make change. It could be as simple as saying yes when we have often been taught to say no – to extend our boundaries and to challenge ourselves. We might take our children to a meeting, as life sometimes requires, and acknowledge that we are parents and also professionals. Perhaps we can simply make time to attend a discussion or a lecture. Women need to be represented in the audience as well as on the panel and the podium. We should take opportunities to speak – this does not necessarily mean giving a lecture, perhaps we could start by asking a question?

As architects and architectural professionals we have a responsibility to engage with the discourse that surrounds architecture and architectural practice. My belief is that conscious engagement raises the visibility of women in the profession. This in turn gives us a voice, allows us to become role models and provides us with the ability to be heard and finally, the ability to create change.

- Liz Ritchie and Dr Hannah Piterman, Women in Leadership Series and Report Leads, Women in Leadership: Looking below the Surface (Melbourne: Committee for Economic Development of Australia, 2011), 9.[↩]

- Dr Karen Morely, Working Paper No. 3: Getting to grips with Unconscious Bias (Gender Worx, 2010), 5.[↩]

7 comments

Stumpjumpper says:

Jun 3, 2012

With all respect to Jeremy Till, to restrict one’s acceptance of invitations to “events/series/books that have at least 30% female representation” is not only arbitrary but counter-productive to the cause of redressing the under-representation of women in architecture.

Would a doctor fighting obesity, for example, refuse to engage with the most obese, arguably those who would most benefit from such engagement? Or, to put it another way, why hide one’s light under a bushel?

To follow Till’s dictum may be to take the route more comfortable intellectually, but it may also prolong the situation complained of.

I suggest that the best way for a female architect to improve the acceptance of women’s skills in architecture is simply to ‘do architecture’ to the best of her ability, in addition to advocating that acceptance by other means.

As Dr Johnson said, “I refute thee thus.’

Put the question to practising female architects. I suspect you’ll find few who would support Till’s suggestion.

The question of unconscious bias is a legitimate one, but it does not legitimise avoiding engagement with those perhaps most biased.

Justine says:

Jun 3, 2012

Hi Stumpjumpper, you might be interested to read Jeremy’s own account of his 30% pledge – also on Parlour https://parlour.org.au/architecture-is-too-important-to-be-left-to-men-alone/

I suspect the politics of Jeremy, as a highly regarded male professor, declining an invitation are a little different to the politics that would attend many women architects declining an invitation.

t_davidge says:

Jun 3, 2012

Hello Stumpjumper –

Thank you for responding to my article. I wanted to clarify that I am in no way advocating decreased engagement by women but rather I am interested in how we might increase the visibility of women in the architectural profession. I believe diversity and equity is an issue for all of our profession (both men and women) and, as such, I used Jeremy Till’s 30% pledge as an example of the way a male academic can help to change the stakes by personally pledging not to accept invitations to events that have less than 30% women participants.

In no way do I advocate this as a position a woman should take if she were asked to participate. In fact, I would hope that she accept the invitation whole heartedly. The aim is to increase participation beyond 30% not decrease it. Apologies if I was unclear on this point. I believe one of the most important things we can do as women in the profession is to increase our visibility and promote the visibility of others so that women’s participation in the profession becomes more widely accepted at every level and creates role models for the next generation of women architects.

On perhaps a more controversial note I do not believe that the best way for a female architect to improve the acceptance of woman’s skills in architecture is “simply to ‘do architecture’ to the best of her ability”. While I very much admire women who excel in our field, I know too many excellent, professional and talented women architects who have stories of bias in the workplace – unconscious or otherwise – to be able to put my faith in this as the primary way of combatting issues of participation. This position puts too much emphasis and weight on the individual and is an issue that needs to be tackled at a broader level.

This is why we all need to support Parlour. It is a fantastic platform that makes women visible, connects them across borders and moves beyond the individual creating a community that proactively supports change.

Stumpjumpper says:

Jun 3, 2012

More power to you, Tania, for having the courage of your convictions and following your instincts to promote discussion on the gender aspect of architecture. As for ‘decreased engagement’. I think even Till would claim that his 30% policy was aimed at more powerful engagement.

I’m not sure that I stand with you entirely, but I belierve that only good can come of discussion and review in the practice of architecture. I read Tiill’s article and I certainly agree that whatever the influence of gender in architecture to date, the role of architect has declined in relation to other players in the procuring of buildings.

To align completely this decline with a gender imbalance in ther profession may be too much. There are also issues such as the rise of consultants, the reluctance of architects to lead projects, for example from fear of liability, and at a domestic level the perceived economics of using an architect when many builders can satisfy the market’s expectations.

None of these difficulties is particulasrly philosophical, and I suggestr that resolving them requires practical rather than intellectual change. That is not to decry intellectual efforts such as openHAUS, provided that openHAUS is focused outwards. Self-contemplation has its place, and it can be a precurser to nchange, but as an agent of urgently needed change it has historically been weak.

Architecture needs change if it is to survive and flourish. It cannot afford to be the province of an elite, regardless of gender.

I feel that the solution is to increase the value of architecture to everyman (and of course everywoman). Consider the design of clothing as an example. It is clear that almost everyone, male and female, from childhood to old age, is interested in how they look. More, we select pens, curtains, cars with careful attention to the different characteristics available.

Surely, we should be as careful about choices in our housing. I don’t think we are, and I suggest that at somewhere near the root of the problem, perhaps at childhood level, is a failure to engage with the idea of housing, particularly among girls.

Here is where Tania and I intersect. It’s a commonplace that boys have blocks and girls dolls. But there is more than that.

I am old – I cannot talk in the language of ‘nuanced reimaginings’, but I know what’s being said.

Many times, I have struggled over a difficult poroiblem of design, to have a woman breeze past and resolve the problemn almost at a glance, using a solution to which I was blind.

Similarly, I have seen men suggest ‘Use a truss’ or whatever, and I’ve seen a woman’s design progress,

Gender balance is not an end in itrself. It is simply a way oif ensuring that male and female minds meet. The two do seem psychologically different – stronger in certain areas and capable of different things.

The whole – the product of both minds, is usually greater than the sum of what might be achieved by both separately.

My ideal two person practice would always comprise a man and a women.

So I agree wholeheartedly. More women are needed in architecture, but not in the sense ofd allowing women into the club, to enjoy the same aloof elitism that many male practitioners have for years.

Architecture itself must becomer more inclusive, so that, like fashion design, everyone feels that they can own a bit of it; everyone feels engaged enopugh to make decisions, whilev respecting the expertise of the expert practitioner.

That way architecture becomes more valued and simultaneously more democratized anbd more open. There is no loss of quality at the top end, and like a coutourier considering the clumsy efforts of the aspirant amateur, it can only be good for trade.

I have seen make architects who are basically reproducing their final project, or somer award winning design – the last design, at any rate, which they truly investigated and resolved to their best ability.

I have seen women of great talent leave the profession, deadened by being given insufficiuent design responsibility and sometimes being frozen out, at the same time, of a blokey office culture.

No situation like that is any good, but not because it is an intellectual affront to some notion of gener – rather, such situations cost the profession dearly – in lost creativity, in perpetuating the myth that one needs male chromosones to contrive a good design, but most of all in continuing to broadcast that the aura of elitism around architecture.

Put bluntly, the paying public aren’t buying it, and they’re voting with their feet. Commissions go to project builders and building designers. To live on, architecture must present itself metaphorically as a retail, ground floor enterprise, with men and women visible through the window, working on projects the passing trade, whether private or otherwise, might buy. If a bunch of male architects want to be part of a club based on gender, they should join one – they still exist – but they should put the welfare of their firm first and there be as inclusive as possible.

There is a place for stunning designs of great subtlety and value, but such work is usually best produced not by starving artists in garretts but as an adjunct to a healthy, widely respected retail practice. Moreover, stunning design can, with care, be introduced into the most ordinary of commissions often at no or little extra cost.

Lack of respect for women is not the problem for architecture. It is lack of respect for architecture itself. If we treat ourselves properly, and properly value the potential of men and women in the practise of design, then we can more easily work on the real engagement that is necessary – engagement with the community.

Good luck, Tania.

t_davidge says:

Jun 4, 2012

Hello Stumpjumper –

We are definitely on the same page and the issue is a complex one. As an architect I am in whole hearted argreement with your last paragraph and it is something I am attempting to explore through my practice. As a woman in practice I try to engage at a big picture level and also at the level of the smaller details in the optimistic belief that the profession is changing in positive ways and that the only position is onwards and upwards for us all.

Thanks for your thoughtful comments.

Fiona Winzar says:

Jul 16, 2012

Yes Architecture does need an improved public profile – a tricky game …….remember we live in Australia.

But within the industry itself women need more opportunities for

an equal footing and need to support one another – one of a few things that men do that we would be be wise to adopt.

A female AIA National President is a good sign, but it won’t be easy to shake up the status quo and long standing entitlements enjoyed by the boys clubs.

Fiona Winzar

JENIPHLER says:

Sep 10, 2012

The architectural profession has a legacy formed by habits, rituals, and human linkages over many years. This structure was created, designed, and promoted by a certain group of men. I have an inkling this group is not entirely gender separated, there are many men who are not fully supportive of the status quo, not just about the attitudes to women. Women can easily be identified as a specific group that is disadvantaged by older ingrained attitudes, but I do not think that is the core issue, as much as it is about gendered principles, which crosses a sexual divide. Having said that, forums specifically about women in architecture allow for conversations outside the architectural cultural norm and encourage innovation and creative dissension.