Queensland architect Dolly Brennan began her long struggle for equal pay almost 100 years ago, and the battle is not yet won, argues Kirsty Volz.

Dolly (Dorothy) Brennan (b.1891–d.1977) is one of Queensland’s early women in architecture. She worked for the Queensland Government’s Department of Public Works from 1910 until 1956. Her contribution to architecture through such a continuous and sustained career was significant and deserving of much greater recognition. Dolly Brennan commenced employment as a draftswoman, moving up the ranks to architectural assistant, until she retired.

In 1935, it was reported that Brennan was the highest paid female employee in Queensland’s public service. However, despite her long career, Brennan was never paid the same, nor promoted to the same senior positions, as her male counterparts. She protested for equal pay, publicly spoke at arbitration court hearings on pay disputes and had her views published in local newspapers. This article discusses Brennan’s fight for equal pay and how her employer justified paying women less to complete the same work as men. It highlights the unequal foundations of women’s pay in the workforce and why it’s important that we continue the conversations that support equal pay.

Brennan’s career commenced before the formalisation of architectural qualifications in Australia. Architects trained through an articled position, usually working as a draftsperson, and completed courses at night offered at technical colleges. Brennan undertook evening classes at the Brisbane Central Technical College (BCTC – now the Queensland University of Technology), and when the BCTC offered a full Diploma of Architecture in 1918, she was one of the first students to enrol. She graduated in 1922 and was awarded the first gold medal for her studies from the Queensland Institute of Architects.

It was during her time studying at the BCTC that the first public appearance of Brennan fighting for equal pay is found. At an arbitration court hearing in 1920, Brennan gave evidence stating that she produced the same quantity and quality of work as her male colleagues and therefore deserved equal pay. The court decided to lift the minimum wage for Queensland’s public servants but maintained that women should be paid less, with the minimum set at £200 for men and £150 for women. The justification for this decision was for two reasons. The first was that a man’s wage had to cover the needs of providing for a wife and three children, while a woman’s wage only needed to cover her own needs. The second was that pay parity would discourage employers from taking on women in the workplace, where lower pay, supposedly, created opportunities for women.

In 1921, Brennan’s employment with the Department of Public Works was terminated. Whether this was related to her fighting for equal pay is unknown. She worked for Evans Deakins and Co. for about one year before returning to the Department of Public Works in 1922.

In 1935, Brennan was interviewed for an article in the Truth in which it stated that Brennan was the highest paid female public servant in Queensland. She was one of nine architectural assistants, and the other eight were men. By this stage of her career, Brennan was a qualified and registered architect with 25 years experience, and yet she only held the position of architectural assistant. In fact, in the 46 years that Brennan worked for the Department of Public Works, she was never promoted to the position of architect. Even if she was the highest paid female public servant, she was still not employed at a level that reflected her skills, qualifications and experience.

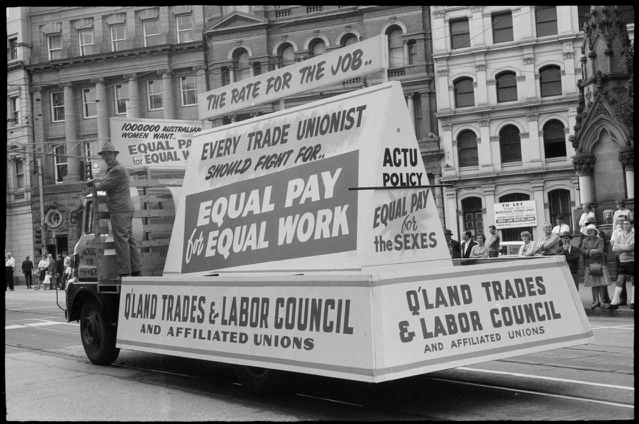

Brennan’s career highlights a history of pay inequality in the profession of architecture. Not only did inequity exist, but state governments legislated that women were paid less than men. While the Queensland state government set a minimum where women’s wages were at least 75% of men’s, this was not made law in Australia until 1950. Then, in 1969, the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Commission determined the principle of ‘equal pay for work of equal value’, although equal pay was not legislated until 1972.

There are still ongoing bigger and broader issues with pay equality that other people are better equipped to discuss than I am, but this historical perspective demonstrates that the foundations for pay in the profession of architecture were not equal. The remuneration that men and women in architecture receive for the same work has a history of a defined inequality. For this reason, the discussions around pay equality need to continue until we can define a correction that makes it identifiably equal.

References:

Bronwyn Hanna, “Australia’s Early Women Architects: Milestones and Achievements”, Fabrications (2002), 12(1): 27-57.

Donald Watson & Judith McKay, A Directory of Queensland Architects to 1940 (St Lucia, Qld: The University of Queensland Library, 1984).

Judith McKay, “Designing women: pioneer architects”, Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland (2008), 20 (5): 169.

“Female Hopes are Fired: Victories Scored in Public Service Appeals”, Truth, 17 February 1935, 20 (accessed via trove.nla.gov.au)

“Public Service Claims in Public Service Court”, Telegraph, 13 July 1920, 2 (accessed via trove.nla.gov.au)

Kirsty Volz is a PhD candidate within the ATCH group at the University of Queensland. Her thesis discusses the built works of Queensland’s early women architects, focusing on the work of interwar architect and ceramist, Nell McCredie. Her research on interior design and scenography has been published in the IDEA Journal, TEXT Journal, Lilith: a feminist history, and the International Journal of Interior Architecture and Spatial Design.