What can statistics tell us about the situation of women in architecture in Australia? Gill Matthewson outlines the data she has collected so far.

The first thing to know is that it is almost impossible to gain a complete or clear picture of the gender situation in numbers, based on current data. While there are data on the proportion of women and men graduating from architectural schools since 1999, no agency tracks how many are employed in the profession. What follows are our first efforts at mapping the distribution of men and women across architecture, both in education and in the profession.

At school

Students in Australia complete two degrees as part of a course in architecture – a first undergraduate degree leading to a second professional masters degree. In 2011 there were 9,222 students studying architecture across these two degrees in Australia.

- 42% of them were women.

- 44% of the intake into Year One of the degree/s were women.

In 2010, 975 students graduated from the second degree, 427 of whom were women (44%). This is consistent with previous years, as shown in the chart below:

Women have averaged 41% of all graduates from 1999–2010. Pre-1999 data is currently not available, but we are in the process of researching this. Anecdotal evidence, combined with evidence from other countries, suggests that the proportion of women graduating with degrees of architecture has been at or near these levels for several decades.

However, this may not in fact be the case. New Zealand data, contained in Errol Haarhoff’s report, Practice and Gender in Architecture: A survey of New Zealand Architecture Graduates 1987–2008, shows a 45% graduation rate for 2001–2010 and 34% for 1991-2000. Although as a smaller country it may be showing some of the odd distortions that can occur with smaller numbers.

Numbers coming in are not the same as numbers going out. Last century (particularly in the seventies and eighties) there was a considerable attrition of women in the schools. This meant that the proportions of women entering the schools was much higher than the proportion graduating. Architecture usually has a reasonably high attrition rate, but it seemed to affect women even more than men. However this trend has shifted markedly over time, with increasing improvements over the years we have data for.

Intake each year this century has seldom varied from around 44% women. In the first five years (2001–2005) women were 40% of the graduates; for the second five years they were 43%. It should also be noted that individual schools have quite different patterns of attrition to the country-wide pattern. However, overall the trend is of equitable attrition.

Teaching Staff. We are in the process of establishing the proportion of women on teaching staff. Our first rough calculation is that they are around 30+% but this is very approximate. And once again individual schools vary considerably – some being as low as 17% and others at 43%. In some schools women comprise a higher proportion of sessional staff than permanent academics.

At work

It is much trickier to establish women’s participation in the profession. If we take registration as a measure: there are 11,474 registered architects in the Commonwealth and 2336 of them are women, that is 20.4%. (For comparison, Paula Whitman’s report, Going Places, tells us that in 2004, women were 14.3% of registered architects.) These figures are far lower that what might be projected from the graduation rates, and lower than the professions of law (46%) and medicine (36%) with which architecture is often compared.1

There are some problems with the registration data. Firstly:

- Each State Register is separate and to do any work in a State you must be registered there as well as your home State. Therefore, there are many architects registered in a number of different States, and the register does not always indicate this. We are working on establishing cleaner data.

- In each State, some architects are ‘inactive’ or ‘non-practising’. Some registers note this and some don’t. We are in the process of separating the figures out. In Victoria, for instance, nearly one third of the gross number of registered architects are either inactive, non-resident or both.

Our current picture of registration state by state is as below:

Secondly, not every graduate of an architecture school who is working in the profession chooses to register. New Zealand research by Errol Haarhof shows that less than 50% of graduates ever register; Australia is likely to be similar. However, it is quite possible to be working as an architect and not be registered. In this respect, architecture as a profession differs markedly from medicine and law where one must be registered or licensed in order to practise.

Canadian research in 2000 recommends the use of Census data rather than registration figures.2 Indeed, the 2006 Australian census shows double the number of women working in architecture than were registered in 2004 and therefore a higher participation figure. (Once the 2011 census has been processed we will be able to update these figures.)

The census also reveals a striking pattern of women ‘disappearing’ from the profession as they age.

Our next step with this information is to map the proportion of graduates per age group (this will be approximate as every group of graduates will have more mature students in it).

Membership of the Australian Institute of Architects

Membership of the Institute is another way of measuring participation in the profession, although it needs to be noted that membership is not compulsory and many architects choose not to belong.

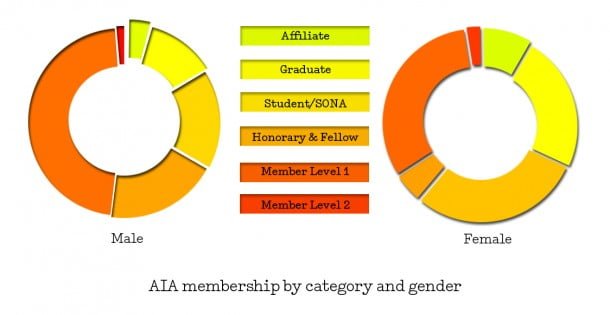

There are, as of 30 March 2012, 11,738 members of the Institute and 3,020 are women – this is 26%, which is higher than the registered proportion. However, there are different categories of membership and the overall pattern of membership differs quite markedly for each gender.

A minimum 61% of the women members are not registered. 3 Membership categories where members are definitely not registered are: affiliate, graduate, and student (these categories are the three coloured yellow and green in the above charts). But with the male membership only 33% of the men fall into these same definitely not registered category.

Overall, 40% of the total membership is in these non-registered categories. This once again indicates that the profession is larger than any registered count can give us, but larger for women.

A similar difference along gender lines is visible when one analyses the membership according to their employer category.

Member Level 1 is the category reserved for those who are directors, partners or equity owners of an architectural practice. This is the category which contains those who have reached the highest level of leadership in the profession.

However, women make up 19% of this membership category (958 women, 4,101 men) – a level comparable to their proportion as registered architects (although under their overall proportion of the Institute).

These statistics have been sourced from a number of places.

At School statistics were extracted from Architecture Schools of Australasia (2000 to 2011 editions, November 2011) by Carol Capp, National Education Co-ordinator, Australian Institute of Architects. This has been supplemented by data from the 2012 edition.

Data on academic staff has been extracted from the 2012 edition of Architecture Schools of Australasia, supplemented by data taken from university websites. Note some sites and entries are clearer to determine who is teaching on the architecture programs than others. Where possible we have tried to limit our count to those teaching on the architecture degrees.

Registration data obtained from individual State Registration Boards in late 2011 and early 2012.

- Heather Moore and Kate Potter, “Advancement of Women in the Profession,” The Law Society of New South Wales (2011) and http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4819.0 [↩]

- Annmarie Adams and Peta Tancred, Designing Women: Gender and the Architectural Profession (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000). The Canadian census figures provided a nearly two-fold discrepancy: registered women architects 10.1%, but in the Census 19.6%.[↩]

- Data from the Australian Institute of Architects, 30 March 2012. Some other categories such as Fellow or Honorary may or may not be registered.[↩]

9 comments

a1005247 says:

May 16, 2012

“However, it is quite possible to be working as an architect and not be registered. In this respect, architecture as a profession differs markedly from medicine and law where one must be registered or licensed in order to practise.”

This is not quite valid. In every state in the Commonwealth, under their Architect’s Acts, anyone calling themselves an Architect MUST be a registered architect. Under all Acts there are severe penalties* for “holding out” (that’s the legal expression employed to describe non-registered person/s describing themselves as Architect/s.

In SA, for instance, under their new Architect’s Act 2009, the penalty for “holding out” is up to 6 months imprisonment and/as well as/or up to $50, 000 fine. This reflects how seriously the pubklic needs to be protected from unregistered person/s being misunderstood to be/ or mistrepresenting themselves to be, an architect (remember, buildings can kill people…).

This is not to suggest that graduates may not call themselves by their degree credentials on their business card, or on their email signature.

“Joanne Bloggs”

“Master of Architecture”

But Joanne/(and her employer), cannot call herself/(her) an architect.

So the question is, why women don’t register in greater numbers?

gill says:

May 16, 2012

It’s absolutely true that there are restrictions around what you can call yourself. But my point is more that you can actually be doing all the work of an architect and not be registered (and not calling yourself one).

Why women don’t registered in greater numbers Is an interesting question, but it also affects men as well. The NZ research reckons that only about 50% of all graduates ever register. We are seeing if we can establish the proportion of women who gain registration each year. Comparing this to the graduation rates will give us more of a picture of what is happening.

a1005247 says:

May 17, 2012

Do you think you could please possibly change the way that this is expressed in the Report online (above)? It is manifestly the same as Law and Medecine in our profession. No unregistered persons may practise as an Architect. To suggest otherwise does your excellent research a disservice, and reinforces a practice which I think does encourage non-registration – that women may think (and I think their employers may be encouraging this to avoid paying at a different pay rate) that there is no disadvantage. There is. Thank you.

gill says:

May 18, 2012

I am interested in mapping the participation of women in the profession. Many graduate with architecture degrees but if we take registration as the only measure of the profession then women’s participation looks very poor.

If the profession is only measured by registration then that profession is supported by huge numbers of people, most of whom have architecture degrees. From talking to them I would say they are doing the job of an architect but under the umbrella of another’s registration. They should be registered and I would indeed encourage them to.

I would not want to encourage the practice of non-registration at all. It’s a poor mode of practice. Some firms work with a business model of few registered, less than 10% and do not encourage staff to register. They actively block staff access to experience of all the parts of work required for registration. This is entirely possible and to the profession’s shame. But it happens and because of it women disappear.

I agree with you that the normalization of this form of practice makes people think its not worth registering and that there is no advantage to doing so. This is not correct and I would say to anyone working in a firm that is not allowing them the experience or support to become registered to leave.

That said, the process of becoming registered is perceived by some to be arduous and expensive, so too is the process of maintaining that registration. This is perhaps something the registration boards might want to look at.

CB says:

Jun 9, 2012

Hi Gill, Great analysis. A question for you: why do we keep comparing ourselves to medicine and law professionals? Both are male dominated fields with hideous work/life imbalance and demands where paid renumeration is at least significantly higher than it is for our profession. Couldnt we look to learn from fields where there are already higher proportions of women? For eg. teaching and care professions? Women chose and remain in these careers despite being underpaid. I suspect its something to do with the “make a difference” motivation identified by Whitman and the flexibility of conditions which allow for a better work/life balance.

gill says:

Jun 9, 2012

Hi CB

You’re right that comparison to both medicine and law is not always a particularly useful one for lots of reasons. It is however commonly done because like those two architecture is a long period of study, much longer than teaching for instance, and has some similar structures for licensing and registration. They are also the kind of professions that architecture aspires to be like: learned, liberal, etc. So they have a hold over the conception of architecture I guess you could say. But I am finding more and more reasons in my research not to make the comparison and will write about that at some stage.

Gill

Felicity says:

Oct 7, 2012

I have my architectural degrees, but will never practice as an architect – instead, i take great joy in managing consultants from the other side of the fence, where the gender divide is even larger….

I think the discussions above are too narrow. I think that not only should we compare Architects (whether or not we have bothered with the tedious registration process or not) with Solicitors and Doctors, but we should be looking further – to the greater business community. Architecture is still a business (despite its theoretical foundations). The lack of progress of women professionally is not unique to architects. I think we need to look at the problem on a larger scale, and really start to look at the foundations of the problems that prevent the progression of women through their careers (Have attached a link to a basic article below exploring the issue). We can then start engaging the blokes! (you know, the people who according to the stats run most of the practices in which female architects work?!) I suspect nothing will change as long as they (by they, i mean those still oblivious) think the issue of a lack of progression for females is just a problem for women to talk about amongst themselves…

http://www.bain.com/offices/australia/en_us/publications/what-stops-women-from-reaching-the-top.aspx

Justine says:

Oct 7, 2012

Hi Felicity, Thanks for your comment. We are familiar with the Bain report and other work from the corporate sector, and agree that it is very helpful – we link to quite a bit of it in the Outer Parlour section of this website. We also hope to have a more complex picture of the contribution women with architectural backgrounds make when we have completed the analysis of our first survey. And yes, it is an issue for everyone – not just women – we are very please that many men are also signing up to Parlour, and we are working to broaden the discussion i a range of ways. Nonetheless I also think talking among ourselves is also helpful – passing on strategies and knowledge can be very productive. It is such a complex issue that it needs to be approached in multiple ways, as you point out.