Annmarie Adams contemplates the home as workplace, the growing importance of domestic architecture and the meteoric rise of the interior as a subject of discussion and study.

Like so many around the world, I’ve been working at home since March 2020. My workplace is now about four feet, rather than four miles, from my bed. Every day I communicate with colleagues and students at my university and indeed around the world through scheduled Zoom meetings, from a little-used dining table we moved upstairs from the basement. In other words, it’s my activity – my ‘work’, rather than a ‘place’ – that now defines my workplace. Our beautiful School of Architecture building at McGill University, in the meantime, sits empty, like much of downtown Montreal.

Views of the now-empty School of Architecture, McGill University. Photographs by Masters student Francis Di Pietro, 2020.

For us architecture peeps, it’s difficult to accept that place may matter less in the post-COVID world. I think about the unoccupied campus every day. Empty public spaces feature largely in the media. Some say we will see the end of the office building post COVID-19; we have all seen images of theatres or meeting rooms, peppered with only a few socially distanced viewers. Streets are abandoned. Libraries, restaurants and a host of other places are ‘take out’ only. Hand-made drawings of rainbows press up against windows, demarcating the newly important threshold of the private home.

Adams-Gossage residence from inside, 26 March 2020, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Downtown Montreal is so barren it resembles an architectural rendering. Photo by C.M. Kelly, 10 November 2020.

This COVID-focused lens on the barrenness of urban space and the comparative vigour of domestic architecture has thus brought new attention to interiors. Not only have we all had eight months to rearrange our closets and reorganise our kitchens, but we have gained unprecedented glimpses of the homes of our colleagues and students online. Home interiors are what we see all day. And because our own worlds are suddenly so contained, we are willing to invest more in them. More time, more money, more study will be devoted to interiors.

Who doesn’t love the Twitter account @ratemyskyperoom, also known as Room Rater? A witty political duo posts bad images and rates the Zoom rooms of media personalities, including wall colours, placement of art and furniture, book choices, and camera angles. “When quarantine began, it didn’t take long for us to come to the collective realisation that we’re a bunch of Zoom voyeurs,” says Slate journalist Heather Schwedel, in a piece that rates the raters. I especially like it when the profiled and clearly domesticated media personality actually responds to Room Raters. And as Schwedel and others have noted, Room Raters has found an uncanny link between good interiors and good politics. The private interior is thus now publicised and politicised.

Room Rater posts on Twitter put public personalities in domestic settings.

In a world where over 1.2 million people have died of an airborne virus, we yearn for safe domestic containment. Viewers from around the world watched as President Trump fled the White House on 2 October, soon after his diagnosis with COVID-19, almost like an expulsion. The newly sick President was then photographed occupying specially designed Walter Reed Medical Center hospital interiors and, three days later, a Chevrolet Suburban SUV, its interiors protected by especially thick doors and windows. Media reports emphasised the containing power of the car: “this is about as far removed from the civilian Suburban that’s most often used for carpooling a kid’s soccer team and towing a boat to the lake house as it gets,” wrote a journalist in Forbes.

Our domestic containers can also be unsafe. Just think of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s short story “The Yellow Wallpaper”, where a home that might appear safe from outside can be a place where we fall apart. Jill Lepore wrote about interiors and mental health in The New Yorker, noting the widespread impact of “staying in”: “living indoors all the time is driving people crazy, staring at the wallpaper, peering out windows, craving nature, and one another, whimpering and howling inside.”

Architectural critics are key agents in the meteoric rise of the interior. Christopher Hawthorne convened mayors, a photographer, and some architectural historians to discuss domestic interiors at a recent USC event, “Inside Out, Outside In: What this unprecedented year means for the future of public and private space,” now on YouTube. I was invited because Hawthorne had seen a blog I wrote about interiors, for a healthcare policy institute at my university and we had communicated on Twitter. We talked about the rise of the interior as an academic subject, including the founding of the SAH Historic Interiors Affiliate Group. The group hosted a wildly successful inaugural event on 21 October, which attracted nearly 300 participants.

The subject of interiors is everywhere, including academic conferences. Interiors in the Era of Covid19, a webinar hosted by the Kingston University, is planned for March 2021. Since the pandemic, many architects have added COVID-inspired design ideas to their list of services, in anticipation of the brave new world ahead. Gensler’s website is a good illustration of how many architects are suggesting that design is the key to a healthier, post-pandemic world. Almost all focus on interiors. Librarians have assembled a really useful bibliography of COVID-related articles documenting how designers have responded to the pandemic. Many sources focus on interiors.

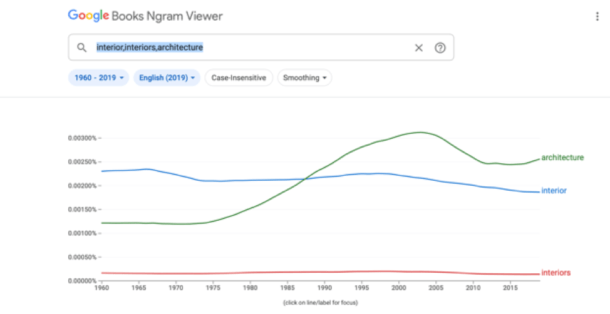

What’s next? As I see it, we need to imagine this extraordinary time ‘inside’ as an opportunity to enrich the ways we study interiors in two major ways. Google Books Ngram Viewer shows no significant increase in the use of ‘interior’ or ‘interiors’ from 1960–2019. If anything, ‘interior’ shows a slight decline. So firstly, then, how about some new vocabulary? So many COVID words are spatial: social distance, bubble, lockdown, quarantine. I would welcome suggestions for creative, COVID-inspired architectural vocabulary.

Google Books Ngram Viewer shows no rise in the use of terms ‘interior’ and ‘interiors’ from 1960–2019.

Secondly, we need to connect domestic interiors with spaces inside other building types. Will the home remain a safe space as more people become sick? What about ‘domestic’ interiors in public buildings? How can we study the interiors of important non-domestic building types such as hospitals and long-term care facilities, when we can’t gain access? In my opinion, architectural researchers must devise new, safe methods for such fieldwork, beyond personal observation and experience. We need to link classrooms to the home to the hospital to the car to the street to social media. We need to embrace the history of interiors as the history of our lives.

Thanks to Peter Gossage, Paula Lupkin, Cigdem Talu, and David Theodore for previewing this text.

Dr Annmarie Adams holds the Stevenson Chair in the Philosophy and History of Science, including Medicine, at McGill University, Montreal, Canada. Jointly appointed in the School of Architecture and Department of Social Studies of Medicine (SSoM), where she also serves as department chair, she is the author of Architecture in the Family Way: Doctors, Houses, and Women, 1870–1900 (McGill-Queens University Press, 1996) and Medicine by Design: The Architect and the Modern Hospital, 1893–1943 (University of Minnesota Press, 2008), and co-author with sociologist Peta Tancred of Designing Women: Gender and the Architectural Profession (University of Toronto Press, 2000).