Architecture practice still seems to be a mode of operating that resists women. A generation after Gill Matthewson and others first asked, “where are all the women?” she is still, with some frustration, asking the same question. This raises a series of further questions. Why does the architecture profession fail a significant proportion of women? Why are the margins more hospitable? Why is the profession, as defined by registration, so decidedly off-limits to alternative practice?

These questions are addressed in Gill’s paper, which focuses on the situation in New Zealand, for Limits, the 2004 conference of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia & New Zealand.

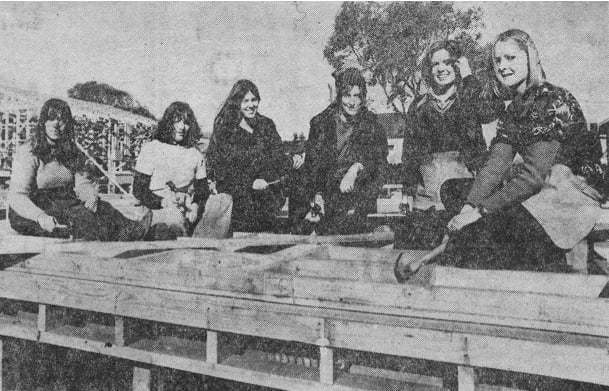

“These Auckland University girls are learning the practical side of their architectural studies…” Gill Matthewson and colleagues, from left to right: Lyn Maltby, Gill Matthewson, Jacqui Gilmore, Janet Thompson, Jane Aimer and Lyndley Naismith. Auckland Star, 9 August 1976.

It is with some annoyance and reluctance that I come to the subject of this paper. Nearly thirty years ago others I, along with others, asked “where are women in architecture?” Apart from in the schools of architecture, women were invisible – both in the profession and the library collection. Given the massive societal and economic changes since then, and our increasing numbers and research, I didn’t think it would be either necessary or indeed possible to be able to ask the question again so many years later. I thought (and hoped) it was past history and had simply been left behind.

In the seventies though, the question was particularly pertinent as a generation of women flooded into the study of architecture in larger numbers than ever before.1 It attached itself primarily to an historical project: we wanted to know about the trickles that had preceded us. We sought role models. At the time, this seemed a reasonable project and, although it proved to be problematic, it did have its uses in setting a background against which we could see and measure ourselves. It also highlighted discrimination and some of the dangers in entering what had been this ‘man’s world.’2

In the twenty-first century the question shifts because women are surely in architecture, but in far smaller numbers than one might have predicted from the seventies flood. The current percentage of registered women architects in New Zealand is a slim 13.4%.3 A friend commented that at a recent Continuing Professional Development course she found herself one of less than 20 women in a room of over 300 people.4 And a number of my contemporaries have either left or are considering leaving architecture. Somehow, despite my hopes, the question “where are women in architecture?” can still be asked. There is, unfortunately, depressingly little new in the observation that women are under represented. But it is a phenomenon that is remarkably persistent and in this paper I want to consider what might have happened.

Where are the women in architecture – again!

Firstly, how ‘bad’ is the situation? After all, this 13.4% of women registered architects still represents 221 women practising architecture in New Zealand; a near ten-fold increase on the 24 registered in the mid seventies.5

They also have a certain visibility in the profession and media. As this figure doesn’t measure the numbers who are practising overseas, etc its lowness does not necessarily mean that all those women who have studied architecture have necessarily dropped out. Although only 5 women registered in the decade from 1966-75, 42 did so in the following decade, and 81 to the mid nineties. The tracking to 2005 currently stands at 141. Consistently the proportion of women obtaining registration in each of those decades has grown strongly. 6 And in the short period from 2000 to today the percentage of women registered has increased from 10% to 13.4%.7 This all represents substantial growth, a snowballing effect even. It would also be expected that there would be a time lag between women entering education, obtaining registration and gaining sufficient age and experience to grow their numbers sufficiently to become statistically significant. So perhaps all we need do is wait…

Except, while figures do show this story of increasing participation, this increase is more glacially slow than snowballing and it’s much slower than a time lag can excuse. Women constituted 33% of the intake into Auckland Architecture School in 1976, by 1987 that figure was over 50%.8 A survey of graduates commissioned by the Architects Education and Registration Board (AERB) found the percentages of women graduates from Auckland 1987–1999 increased from 22 to 43%, and averaged 34% for the period.9 Still lagging entry figures but much higher than registration rates where a gender split was discovered: 34% of surveyed male graduates were registered but only 22% of the female graduates.10 Fewer women are registering than their student and graduate proportions might predict. The 13.4% figure is also compromised because a number of registered architects do not have a current Annual Practicing Certificate and are therefore deemed inactive. Women make up 20.9% of that group leaving the active rate at just under 13%. Women are also not visible in the architectural press in any proportion comparable even to their registration rate. In the past year Architecture New Zealand has profiled only one project out of twenty-five with a woman lead.11

Although women had indeed entered (and are still entering) the study of architecture in high numbers, less of us are graduating, less again are being registered, a further proportion of those are inactive and our visibility is poor. At every step of the way the attrition of women is high indicating that limits exist. Francesca Hughes observes that women’s absence is “very difficult to explain and slow to change.”12

Why numbers matter

I want to examine why it is that this proportion of numbers is considered important. This is what Bronwyn Hanna calls a product of a ‘liberal feminist approach’ to women and architecture wherein a more equal percentage of women is read as an indicator of equality of opportunity and conversely unequal numbers is indicative of discrimination barring women’s progress.13 There is no doubt that such limits exist: a study in the USA found that in addition to the usual stresses of architecture, women and other minorities face “isolation, marginalisation, stereotyping and discrimination.”14 A 2003 RIBA/UWE report on why women leave architecture found that reasons included unequal pay, sidelining, glass ceiling, and macho, paternalistic and sexist work cultures.15 Kingsley and Glynn note hesitancy in people claiming discrimination for fear it “will be interpreted as a childish display of crying, ‘But it’s not fair!’”16 Or fear it used as an excuse. But they also argue that refusing to acknowledge discrimination is not just unfair, it is unjust. Architectural practice still seems structured to resist women and diversity.

Even so, things may not be quite as simple as that: equality of opportunity may not necessarily result in equality of outcome. To argue for equal numbers full stop, is to also argue that any short fall is necessarily a product of insidious discrimination and so locks women into an economy of failure – into the role of victim. I am hesitant to portray women only as perpetual victims (just as some women are reluctant to claim it and I was reluctant to look at the subject).17 Not that discrimination isn’t an issue – it clearly is – but we are also subjects who grow and change and may find that architecture in the end just ‘doesn’t do it for us’ for all sorts of reasons. When I asked a friend why she thought women including herself were no longer in architecture she shrugged and said: “We’ve all moved on.”18

The difficulty with this ‘moving on’ or leaving is that it feeds into a loop that architecture is not for women and reaffirms hidden assumptions that women are just ‘dabbling’ until they decide to do the ‘right thing’: get married and have children.19 It plays directly into the hands of those who believe that women are not committed enough, or simply not capable. For instance, the RIBA/UWE report cites the media, rather than waiting to hear the results of the report, “dwelt on the extent to which women are capable of becoming architects in terms of 3D visualisation skills.”20 This is an old argument and is based on some psychological studies from over 40 years ago. Garry Stevens notes that although “some relationship had been found between various spatial ability tests and performance in architecture… the correlations were quite small… [or] only modest.”21

In the end these studies can only conclude that any individual is a complex interaction of numerous factors and no single measure can suffice as an indicator of capability in architecture. Besides arguments about capability are rendered redundant by the increasing numbers of women practising. But, those who are leaving do indeed complicate things.

Why do women leave?

Women leave architecture for complex reasons. The RIBA/UWE report investigating the phenomenon found that “it is the accumulation and drip drip of… negative experiences rather than one single over-riding issue.”22 And these reasons do not just include the discriminatory practices out-lined above, they also list poor employment practices such as low pay, long and inflexible working hours, no job security; increasing regulation (high litigation and insurance costs), high stress, little scope for creativity, and even boredom.23 Such conditions also mean men leave and the report therefore argues strongly that shifts in conditions would improve the retention of all practitioners – not just women.24 The USA study found that “all architects struggle to survive in a profession where the educational preparation is long, the registration process is rigorous, the hours are gruelling and the pay is low.”25 As one interviewee put it: “The image of architecture is much more glamorous than the reality. It’s actually a high-stress, low paying profession.”26

These reports study the American and British situations and practice does vary between countries. Even so, something similar occurs in New Zealand. The AERB survey of graduates from 1987-99 found that the lack of attainment of registration is not just limited to women: “the percentage of New Zealand architecture graduates likely to seek registration does not exceed 50%.”27 The drop-off we see in women is also there, albeit to a lesser extent, for men. Any statistics need close examination. If the low proportions of women graduates attaining registration can be used to demonstrate the limits faced by women as I have done above, what does the overall attrition rate for all graduates mean? The study of architecture is seen as inherently interdisciplinary straddling arts and sciences, incorporating humanities and technology. As such, graduates are thought to have a breadth of opportunity to move into a wider range of directions than the architecture profession itself. Even so 50% of graduates is a high figure to account for.

This begs the question whether registration is really a sufficient measure of involvement in architecture. The report for the AERB raises this point and argues that membership of the New Zealand Institute of Architects with its range of membership categories that “provide an environment for a broader involvement in the profession” is a better indicator.28 Two thirds of all graduates surveyed are members.29 It also cites anecdotal evidence that many of the remainder (a further 10–20%) are likely to be overseas or in post-graduate study.28 The report concludes is “that despite indications to the contrary, most BArch graduates will seek careers in the discipline of architecture with a relatively small proportion entering other fields.”30

So if account is taken of margins of architecture, if the definition of the profession is broadened, the figures would improve – I know of many men and women operating as architects and in worlds I would consider architecture that are not registered.31 Some speak of not registering because they believe it would limit their practice (registration has a strong emphasis on how one comports oneself in relation to others in the building process). But although registration is a poor indicator of involvement, it is the only legal indicator. Registration precisely marks the limits of the profession; those without it are unable to call themselves ‘architect.’ In New Zealand, like other countries, a law protects the word. This law is currently under revision and the NZIA is lobbying to stop a change to protect the phrase ‘registered architect’ only, thus opening the field to ‘all sorts of people’ calling themselves architects.

Defining the profession

The words practice, discipline and profession cannot be used quite so interchangeably as I have been doing. While the former have a wide-ish ‘interdisciplinary’ scope, the last is tightly bound. In his book on architectural distinction, The Favoured Circle, Garry Stevens discusses analyses of professions. Although he goes on to complicate the concept it is worth investigating the establishment of the architectural profession. This was essentially the marking out of profession territory or jurisdiction, the setting of limits. A profession classically involves long formal training and work experience followed by a testing that is a guarantee of competence. A state-sanctioned autonomy and monopoly are sure signs, as is a sense that a profession is “‘higher,’ nobler, and more prestigious” calling serving the public good.21 With architecture “the formation of professional associations of architects in the first half of the [ninetheenth] century [were] attempts to define the architect and exclude mere builders.”32 This involved a phasing in of degrees from accredited architecture schools that “adopt[ed] the Beaux-Arts stylistic system… which provided a rational design system that could be formally taught in schools… and a coherent disciplinary framework within which a market for unique services could be sustained.”33 It necessarily involved a downgrading and phasing out of the apprenticeship system, which had it roots in the building trades from which architects were trying to distance themselves.34

The shift away from building is also a shift away from what in the western world is an explicitly male territory. A recent British Equal Opportunities Commission report in Britain found that women make up just 1% of the construction workforce.35 Perhaps the strongest illustration of this territoriality is the classic wolf whistling from sites. Such whistling (now politically incorrect) was perhaps not so much about threat but marked a deeply-felt strong gender segregated spatiality. It is an act that consolidates the system of mateship/male bonding that still defines the building site. Judy Wajcman argues “physical toughness and workplace conditions that are dirty and dangerous are suffused with masculine qualities… ‘machine related skills and physical strength are fundamental measures of masculine status and self-esteem.’”36 The nature of the work in building, “‘doing,’ is central to notions of masculinity in New Zealand society.”37 From the cliché of the ‘bloke’ constructing anything with #8 fencing wire and a bit of 4b’2 to ‘Bob the Builder’ there is a notion of masculinity that claims building as very much an appropriate male occupation.

This segregation into ‘men at work’ and women on the other side of the fence obviously confirms the notion that women would be/are out of place on the construction site. But it is a site that is also resistant to male architects. In their clean, often-expensive attire they look out of place and with their ‘Escher’ drawings that can bear little relation to the pragmatics of construction, architects are the focus of humour and some scorn.38 So for the building site a woman architect is not so different from a male architect and the site tests both.39 Indeed Kingsley and Glynn discovered that “the construction site was not the primary area in which women graduates identified the existence of discrimination; statistically it fell far behind discrimination by employers and clients.”40

The distinguishing of the profession of architecture from the occupation of building involved the setting not only of jurisdictional boundaries of work but of the character of the architect, which set up an opposition to certain notions of masculinity. The American Institute of Architects (AIA) “took the position that an architectural degree certified not only that an applicant possessed a particular level of skill, but also that the holder of a degree was a person of ‘established character,’”41 and “the objective of architectural education must be the breeding of gentlemen.”42 A gentleman set up a clear distinction from the supposed culturally unrefined rough trade of the builder. Still today in Italy the study of architecture is regarded as a “mechanism for entering a cultural elite.”43

But this mechanism also triggered a series of assumptions about ‘what an architect is’ that were fiercely organised along lines of gender. A gentleman is defined by both his attainment of culture and his treatment of women/ladies as the ‘fair’ or ‘delicate sex,’ with strict perceptions on what women were able to do and how especially one must look after them. The masculinity of the gentleman is defined in opposition not just to the brute masculinity of the builder but also to the femininity of women. In what Hanna describes as post-modern feminism women are understood as ‘other’ to men; men define themselves by what they are not.44 So at its foundation the architecture profession established itself as a particular kind of male-only pursuit pursued by a particular kind of man, both positioned by their ‘otherness’ to women/femininity.45

The origins of the profession in this social class still echo today. Stevens argues that although professions “take the deployment of specialised knowledge as central to [their] definition,” social factors (who you are) are equally, and sometimes more, important than what you know.46 Hidden also within this gentlemen’s description is not just a social but also an economic assumption, to concern oneself with money was not ‘gentlemen-like.’ And easily done if one had/has other means of support. Auckland architect, Wendy Shacklock hesitates to encourage people to pursue architecture claiming that it is “enormously competitive and I’ve been lucky in that I haven’t had to do it to feed a family.”47 Shacklock’s practice is underwritten by her partner and I know of many other similar situations. The low pay in the profession experienced by some architects is a not uncommon reason for people to leave. These social and economic limits to involvement in the profession constitute structural resistance and are part of what Hanna calls a socialist feminist analysis.48

The establishment of the border between builders and architects has been described as a “turf war.”49 The war analogy was also invoked when women started moving into architecture. Hanna points out “comments… describe early women architects as invaders or usurpers… The metaphor of invasion evokes an image of rightful citizens of an established territory being overrun by outsiders who will corrupt the established culture.”44 The fight or battle persists also in descriptions of the process of designing and building. Some women who have left architecture have expressed to me their relief at not having to fight any more. A battlefield requires a certain mode of operating in order to survive. The profession is renown for long hours – architecture is not architecture without all-nighters and rushes to meet often-arbitrary deadlines.50 The sense of solidarity and badge of honour generated from such practices can be addictive, so too can be the adrenalin one receives with the sudden calls to site to remedy problems – architect as hero rushing to the rescue. Once architecture is conceived of as a battle, it could be said that the ‘war’ for women’s entry is lost. In battle certain attributes will succeed: a fierce division into right and wrong, a ruthless ‘winner-takes-all’ attitude, heroic behaviour and ‘mastery’ over forces. All of which favour the competitiveness and aggressiveness that psychologists regard as masculine traits. (This does not mean that women cannot be competitive, it just means statistically speaking that more men than women will have this quality in a sample group.)

Women in the seventies breached the citadel of architectural education and the result was the flood into architecture schools. The expected flood into the profession has not happened to the same extent because it is more carefully guarded: by law and by structures that construct the profession as combative and “fundamentally masculine.”51 When women talk about practice they will often be reported as working in different ways using different processes; rather than competition or fights they will speak of co-operation, collaboration. Marguerite Scaife talks of feeling “uncomfortable with the image of the architect as authoritarian figure.”52 Claire Chambers is explicit in operating in ways that obviate the need for late, long hours or rushes onto site to resolve an urgent problem by proper time management and documentation.53

There are no clear lines here. Architecture has always been about collaboration, it is just that women acknowledge this and now so too do some historians. 54 Beatriz Colomina calls it “the dirty little secret” of architecture.55 It is suspicious to me that the architectural media still promulgates a value system that includes representing projects in styled glossy photographs and under-attributed.56 Wellington architect Barbara Webster “finds sufficient satisfaction working quietly and professionally to meet the needs of her clients and it is that, rather than any external mechanism, which is her measure of success.”[60. Bartley, ‘Reconstructing the agenda,’ p. 40.] This explains some of the invisibility of women in the architectural media.

The suggestion that women might be different in practice and concerns finds us at the limits of liberal feminism, which argues that women and men are inherently equal. Liberal and post-modern feminism argue instead that men and women are equal but different. That politics of difference has informed much work in the academic discipline of architecture concerned with architecture’s monolithic certainty. Consequently theoretical projects of opening architecture up, finding slip-planes in its structure have been occurring for a number of years. These operate at sophisticated levels and draw on the works of particularly French philosophers. Derrida and Deleuze are oft cited and for feminists, Cixous and Irigaray. With concepts such as the fold, the body and sexual specificity, temporality, etc they offer many tactics for thinking about architecture, but few seemed to have crossed the line into the practice of architecture, and those that do have affected the built form in strictly formal ways. So at the moment when discourse is prising open alternative aspects to architecture and challenging its limits, the practice of architecture concentrates on and rewards formalism, either that of neo-modernism or the complex formal possibilities available through computer power (as in the work of the Gehry office).

For architect Martine De Maeseneer “[f]orm has always been a male preserve,” and requires an absolute control over the built form.57 Scaife speaks of letting go control and “allowing the design and indeed the construction process itself to be an interactive process between the client, the architect and the tradespeople involved.”58 Formalism and its role in architecture is a much larger discussion. All I can record is that, for me, it is suspicious that just as women started moving into architecture (arguably on a platform that emphasised social justice) architectural practice shifted strongly to formalism and ignores the social. In Australia and New Zealand this often manifests as the neo-modernism of beach houses (which by their sporadic use erase the everyday, the domestic, that which in traditional terms has been seen as the female realm).

In response to the question ‘where are women in architecture?’ or what happened, there is I think no straightforward answer. Women do appear to leave architecture at all stages but not as much as the statistics imply. It is also too confusing to tell whether we jump or are pushed – more likely it is a combination. However, it seems clear to me that the profession’s basis in the social milieu of the gentleman has echoes that are still felt over a hundred years later. These echoes act against women and are seen in the way architecture is structured as a battlefield, which exhausts women more than men; in how architecture, at times and for some, only seems viable if a partner earning money in another field can provide support; and in how architecture’s nature as collaboration is still under-acknowledged in architectural media.

Such factors push some women shift their practice away from the battlefield and consequently become less visible statistically within the profession. This means women occupy the margins of architecture, at its limits. If we accept women as ‘other’ to men and architecture (and it seems at times that we have no choice) then embracing that could be a tactic. Hughes argues that it is “women’s ability to be central and marginal simultaneously that will allow women to expand the territory of architecture.”59 Groat and Ahrentzen believe that “creative advances in the field may depend on the substantive contributions… of those who can challenge and explore the boundaries of the discipline… the most significant work can be uncovered ‘simply by walking along its boundaries.’”60 If women have been a not always successful breach in the armour of architecture, that perception can shift away from metaphors of war and to the women’s ‘breech:’ breech birth, which could be interpreted as coming at the world from a completely different direction.

Take it to the Limit: Women and the Architectural Profession,’ was first published in Harriet Edquist & Hélène Frichot (eds) Limits, Melbourne, Australia: Society of Architectural Historians, Australia & New Zealand, 2004, pp 319-325.

- In 1976, my first year of study at the University of Auckland School of Architecture, the class was 33% women – historically the highest intake by a sizeable proportion. Second year was 23%, third year 14% and fourth year 16%. Data extracted from “Old Heavy Breather Network Annual – 1976,” address list of all students.[↩]

- Some of its flaws I have investigated elsewhere see Gill Matthewson ‘Pictures of Lilly: Lilly Reich and the Role of Victim,’ in Additions to Architectural History, proceedings of the Nineteenth Annual Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians of Australia and New Zealand, Brisbane, October 2002, on CD Rom.[↩]

- Figures obtained from the Architects Education and Registration Board print-out of members at May 2004. Thanks to Alan Purdie, Registrar, for supplying it. These figures are consistent with those in the US, Australia and the UK: 13% in 2002.[↩]

- Reported by attendee Christine McCarthy. Personal communication. CPD course Wellington 2003.[↩]

- These figures and those that follow obtained from the AERB registration book, thanks again to Alan Purdie, Registrar, for allowing me to review it. The 1964 Architect’s Act meant that all architects had to re-register at this time so twenty-three women were registered and current at the end of 1965. Five more women registered in the decade to 1975 but four retired. Note: the register is not consistent on retiring dates. Also identification of women is based on being able to identify first names as female allowing some names (like Leslie, Robin, etc) to slip through the net although second names usually clarify the matter.[↩]

- 1966–75: 1%, 1976–85: 9%, 1986–1995: 14%, 1996–2004: 24%. Figures collated by author from data received from AERB.[↩]

- From a 2001 report prepared for the Architects Education and Registration Board by Professor Errol John Haarhoff, Women and the Architecture Profession in New Zealand: A Survey of Architecture Graduates 1987-1999, Auckland: Auckland Uniservices, p. 8.[↩]

- See footnote 1 above for the 1976 figures. Thanks to Christine McCarthy for the 1987 figure.[↩]

- Haarhoff, Women and the Architecture Profession, p. 13.[↩]

- Haarhoff, Women and the Architecture Profession, p. 18.[↩]

- Survey conducted by author for the period July 2003 to June 2004. Note, the journal has a new thematic approach to issues such that one issue will look only at say educational buildings. This means that for the period in general large projects were profiled. Women were present in teams for a third of the projects profiled averaging up to 23% representation. Identification of women was based on Christian name indicating gender and there are a number of ambiguous names. Even taking those into account women were present in less than half the teams but in proportions that ranged from 7–33%.[↩]

- Francesca Hughes, ‘An Introduction,’ in Francesca Hughes (ed), The Architect: Reconstructing Her Practice, Cambridge MA & London: The MIT Press, 1996, pp. x-xix, p. x.[↩]

- Bronwyn Hanna, ‘Questioning the Absence of Women Architects in Australian Architectural History,’ in Andrew Leach et al (eds Formulation and Fabrication, proceedings of the Seventeenth Annual Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians of Australia and New Zealand, Wellington, November 2000, pp. 239-250. P. 241.[↩]

- Kathryn H. Anthony, Designing for Diversity: Gender, Race and Ethnicity in the Architectural Profession, 2001 Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press, p. 4.[↩]

- Ann de Graft-Johnson, Sandra Manley & Clara Greed, Why Do Women Leave Architecture? RIBA & University of the West of England, 2003, p. 3.[↩]

- Karen Kingsley & Anne Glynn, ‘Women in Architectural Workplace,’ in Journal of Architectural Education, 46, 1 (September 1992): pp.14-20, p.14.[↩]

- My hesitancy is also shared by others. See Kingsley & Glynn, ‘Women in Architectural Workplace,’ p.14.[↩]

- Personal communication April 2004 with Heather Ives – now a bereavement counsellor.[↩]

- Kingsley & Glynn, ‘Women in Architectural Workplace,’ p.18.[↩]

- De Graft-Johnson et al, Why Do Women Leave Architecture?p. 27.[↩]

- Garry Stevens, The Favored Circle: the Social Foundations of Architectural Distinction, 1998, Cambridge MA & London: The MIT Press.[↩][↩]

- De Graft-Johnson et al, Why Do Women Leave Architecture? p. 28.[↩]

- De Graft-Johnson et al, Why Do Women Leave Architecture? p. 3, 26.[↩]

- De Graft-Johnson et al, Why Do Women Leave Architecture? p. 4, 26.[↩]

- Anthony, Designing for Diversity, p. 4.[↩]

- Cited Anthony, Designing for Diversity, p. 163.[↩]

- Haarhoff, Women and the Architecture Profession, p. 17.[↩]

- Haarhoff, Women and the Architecture Profession, p. 29.[↩][↩]

- Haarhoff, Women and the Architecture Profession, p. 28.[↩]

- Haarhoff, Women and the Architecture Profession, p. 29. Also Kingsley and Glynn ‘Women in Architectural Workplace,’ in the USA found that 91% of their surveyed graduates from 1978–88 were in positions in the architectural profession in 1992; p. 15.[↩]

- For instance the woman named as project architect in that one project in Architecture New Zealand above is not registered.[↩]

- Analysis by Magali Sarfatti Larson described in Stevens, The Favored Circle, p. 21.[↩]

- David Brain paraphrased in Stevens, The Favored Circle, p. 22.[↩]

- Stevens, The Favored Circle, p. 23.[↩]

- Elizabeth G. Grossman & Lisa B. Reitzes, ‘Caught in the Crossfire: Women and Architectural Education, 1880-1910,’ in Ellen Perry Berkley & Matilda McQuaid (eds) Architecture, A Place for Women, Washington & London: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989, pp. 27-39, p. 29.[↩]

- Cited in Lucy Ward, ‘Female builders could bridge gender gap,’ in Guardian Weekly, May 13-19, 2004, p. 8.[↩]

- Lovelock, ‘Men and Machines,’ p. 130.[↩]

- Thanks to my brother Jeremy Matthewson, a builder, for this construction site perspective of architecture drawings.[↩]

- The classic for women is being game to climb a ladder. Once done they are accepted.[↩]

- Kingsley & Glynn, ‘Women in Architectural Workplace,’ p.16.[↩]

- President of the AIA in 1901, cited in Grossman & Reitzes, ‘Caught in the Crossfire,’ p. 29.[↩]

- AIA education report 1906–7, cited in Grossman & Reitzes, ‘Caught in the Crossfire,’ p. 30.[↩]

- Stevens, The Favored Circle, p.29.[↩]

- Hanna, ‘Questioning the Absence,’ p. 249.[↩][↩]

- The persistence of this view and the predominance in the profession of white, middle-class men was discussed by John Morris Dixon in a 1994 Progressive Architecture article suitably entitled ‘A White Gentleman’s Profession?’ November 1994, pp. 55-61.[↩]

- Stevens, The Favored Circle, p. 34.[↩]

- Cited in Marie Clelland, ‘Drawing Room,’ in Architecture New Zealand: Journal of the NZIA, Jan/Feb 2004, pp. 102–103.[↩]

- Hanna, ‘Questioning the Absence,’ p. 244.[↩]

- Grossman & Reitzes, ‘Caught in the Crossfire,’ p. 35.[↩]

- Architecture is by no means the only occupation to be marked by such practices, the ‘global’ economy seems to demand instantaneous response, but it has been endemic in architecture for a particularly long time.[↩]

- Hanna, ‘Questioning the Absence,’ p. 246.[↩]

- Cited in Alison Bartley, ‘Reconstructing the agenda,’ Architecture New Zealand, Nov/Dec 1993, pp. 36-41, p. 37.[↩]

- When I began work with her in 1985 she promised me she would never tell me at 5 o’clock that she needed a drawing done by 10 the next day. She also once shocked me by telling me she didn’t want me to work in the weekend even although we had a heavy workload. For her work confined to reasonable hours was work more efficiently produced and more professional.[↩]

- See Sherry Ahrentzen & Kathryn Anthony, ‘Sex, Stars, and Studios: A Look at Gendered Educational Practices in Architecture,’ Journal of Architectural Education, 47 (1): pp. 11-29, p. 15.[↩]

- Beatriz Colomina, ‘Collaboration: The Private Life of Modern Architecture,’ Journal of Architectural Historians, (58) 3 (September 1999): pp. 462-471, p. 462.[↩]

- In Architecture New Zealand surveyed in note 11 above, the full team of those working on projects are only listed for the main profiled projects. One main project was attributed only to the firm. And it was not possible to determine whether NZIA Award winners for instance included women as only the firm name was credited.[↩]

- Martine De Maeseneer, “Rear Window,’ in Hughes, Reconstructing Her Practice, pp. 26-51, p. 28.[↩]

- Bartley, ‘Reconstructing the agenda,’ p. 38.[↩]

- Hughes, ‘Introduction,’ p. xv.[↩]

- Linda N. Groat & Sherry B. Ahrentzen, ‘Voices for Change in Architectural Education: Seven Facets of Transformation from the Perspective of Faculty Women,’ in Journal of Architectural Education, 50, 4 (May 1997): pp 271-285, p.271.[↩]